Peru and Chile Gold Mine Projects Address Water Concerns

The mining companies behind the Conga and Pascua-Lama mines are working to gain support from communities who have been worried about water pollution and adequate supplies.

Decisions by developers to prioritize water stewardship and community relations at two of the largest and most sharply contested mining projects in South America — the Conga gold mine in Peru and the Pascua-Lama gold mine in Chile — may breathe life into the stalled mines after years of public opposition.

Peru and Chile are at the forefront of a mining boom in South America that is driven by the rapid rise in gold and copper prices within the past two decades, though a recent drop in gold prices is putting a damper on the industry. Mining companies have been pouring money into the two countries. Peru has had almost $US 10 billion in mining investment annually over the past two years, while Chile estimates it will receive $US 105 billion over the next decade.

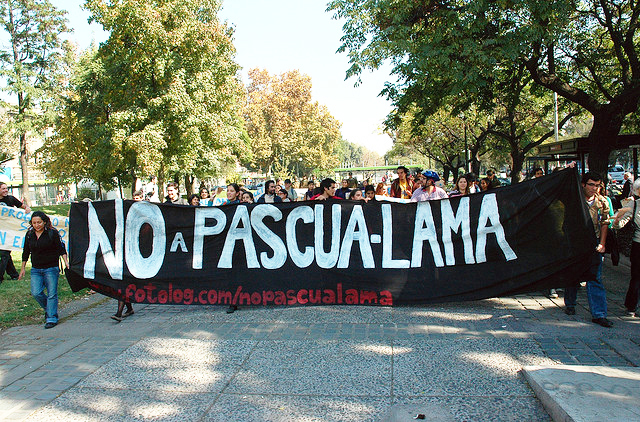

Protests, lawsuits, and rising costs, however, have so far stymied the $US 5 billion Conga gold mine and the $US 8.5 billion Pascua-Lama gold and copper mine. Expected to be the crown jewels of the continent’s new mining movement, the projects are instead facing a new reality in which both local and global communities can make their concerns — many of them about access to clean, plentiful water — heard and heeded.

The Conga and Pascua-Lama projects have both been the recipients of unfavorable public opinion. In 2012, the Conga mine, a venture of Colorado-based Newmont Mining, was put on hold following violent protests that killed five people in the northeast Peruvian region of Cajamarca. In 2013, Toronto-based Barrick Gold’s Pascua-Lama mine stalled after Chile’s Copiapo Court of Appeals suspended construction at the site. Both incidents hinged on confrontations with local communities over water supplies and pollution.

Nonetheless, the companies have not abandoned the projects, and signs point to the possibility of construction resuming at the mines.

Earlier this month, Peru’s Environment Minister said that Newmont is making progress talking with community groups and he believes the parties can reach a “mutual understanding”, according to reports from Bloomberg News. The reports also cited Newmont’s commitment to putting water first and gaining community support before moving ahead with the Conga mine.

Peru’s federal government has also committed to shortening waiting times for environmental permits for mining and hydrocarbon projects in order to attract more investment. Nonetheless, the Cajamarca region — home to the Conga project — recently reelected regional president Gregorio Santos, who has long campaigned to stop the mine, Reuters reported. Santos is currently in jail pending a corruption investigation.

In Chile, Barrick Gold recently announced its decision to hire a new project director for the Pascua-Lama project. The director’s primary task, for now, will be overseeing progress on the site’s water-management system, Reuters reported. In May, the company signed a memorandum of understanding with 15 of the 18 community groups that have opposed the mine. By signing the memorandum, Barrick agreed to provide more project details and to fund expert reviews. Barrick has already spent $US 5 billion on the mine but is waiting to resolve its legal issues with Chile — not to mention waiting for a more favorable market — before resuming construction. Dialogues with the community groups could last two years, according to Reuters.

Sources: Bloomberg News; Mining.com; Reuters

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!