Rio Tinto’s Michigan Nickel Mine Introduces Citizen Water Quality Testing Program

Despite skepticism, company agrees to finance environmental monitoring at Eagle Mine

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

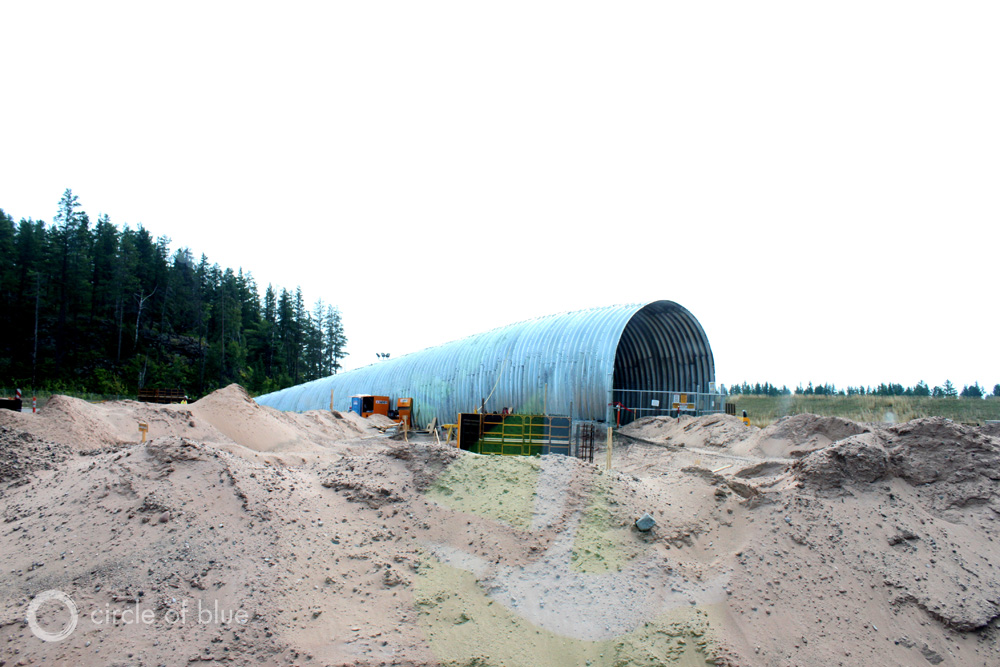

Scheduled to begin production of nickel and copper next year, the Eagle Mine is the first new hard rock mine to open in northern Michigan’s Copper Country in decades. It’s so new that Chevy pickups need Kevlar tires to prevent blowouts on the sharp edges of stones not yet worn by mine traffic.

Puncture-proof tires, though, are hardly the only distinctions that separate the Eagle Mine from others in Michigan or across the United States. Two years ago, Rio Tinto, the mine’s developer, made an unusual proposition to the nonprofit Superior Watershed Partnership and Land Trust, a local environmental organization.

Upended by a decade of civic protest over opening the Eagle Mine in the ecologically sensitive Yellow Dog Plains, the London-based mining company, which operates all over the world, wanted to try something very different in Michigan’s wild and water-rich Upper Peninsula. It offered to fund the Watershed Partnership to monitor environmental parameters, like water and air quality.

The idea was to build trust, and prove to critics that a modern mine—especially a so-called “sulfide” mine that contains ore capable of creating acid mine drainage when exposed to air and water—can operate within permitted requirements.

The Watershed Partnership initially rejected the offer. Taking part in such a program would be a reversal from the Watershed Partnership’s earlier stance on mining. In its 2007 Watershed Management Plan for the Salmon Trout River, which runs through mine property, the organization included a recommendation to “work with local, state and federal partners to prohibit sulfide-based mining.”

“The board was unanimous in saying no,” said Jerry Maynard, a retired corporate lawyer and board member of Watershed Partnership.

“We did not want to put our reputation at risk by working with the mine.”

An Unprecedented Agreement

After mulling the idea over, however, the Watershed Partnership made a counteroffer to Rio Tinto that predicated the group’s participation on these conditions:

- The Watershed Partnership’s monitoring program needed to be completely independent. Mine managers could not influence when, where or how the sampling was conducted.

- The program had to have adequate funding to ensure it was technically robust.

- The process needed to be completely transparent.

- Community input must be included.

“Under Michigan law, they’ve got the right to mine,” Maynard said in an interview with Circle of Blue, noting that Michigan approved the mine in 2007. “It’s going to happen. If it’s going to happen, it is better to have them monitored.”

Rio Tinto agreed to the conditions. Two legal documents were drawn up to govern the relationship between the company, the Watershed Partnership and a community foundation that would act as a “firewall” for transferring the funds.

The Eagle Mine monitoring agreement is extraordinary. Nothing like it has ever been negotiated between a mining company and a local environmental group. The agreement includes a provision that enables any of the program’s findings to be used in a lawsuit.

The agreement sets up a dispute resolution framework involving a board of representatives from the mine, the Watershed Partnership and the local community. Rio Tinto also agreed to support the program with $US 300,000 in annual funding.

In November 2012, the Watershed Partnership launched the monitoring program, which 1) provides verification of the air and water quality samples Rio Tinto takes to fulfill permit requirements, and 2) conducts additional monitoring of parameters not covered by state permits. The monitoring takes place at the mine site near Big Bay, Mich., at the Humboldt Mill near Champion, Mich., where the ore will be processed, and along the transportation route in between.

Already, the program has alerted the public to potential water quality threats. Earlier this year, it found trace amounts of uranium in samples of water from the mine site and released the information to the community despite Rio Tinto’s requests to withhold it until further studies could be completed. Later tests confirmed that the uranium is effectively removed by the mine’s water treatment plant and poses no risk to groundwater. Furthermore, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality has added radioactivity testing to its permit sample requirements.

“It is gaining the trust and respect of the community,” Maynard said. “We want this to get out there—we want other mining communities to say ‘we want this too.’”

Questions Linger About Untested Model

The Watershed Partnership has no enforcement power if pollutants are found. That job falls to the state Department of Environmental Quality and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Maynard said that the Partnership’s greatest weapon is publicity.

“Hopefully there won’t be any significant impacts, or it wouldn’t be allowed by the permits,” he said.

Some skeptics, including the Keeweenaw Bay Indian Community in L’Anse, Mich., view the program as a public relations stunt and have declined their seat on the dispute resolution board.

“It was a tribal council decision not to participate in the committee,” said Jessica Koski, mining technical assistant for the KBIC. “The tribe had already begun work with the USGS to do our own monitoring of water quality, and we didn’t want to play into this public relations thing that the company is doing. But we don’t think it is anything bad, and there have been good outcomes.”

Koski added that the tribe has not been able to point to any examples of sulfide mines that have not polluted the environment in some way. She also questioned whether the company would continue to fund the monitoring program throughout the mine’s expected eight-year lifespan, and noted that the mine has not yet started operations.

A Mining Renaissance

The Eagle Mine is viewed as either on the leading edge or the troubling future of a mining renaissance in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, a region that has seen more mining bust than boom in the past 50 years. Just as in the oil and gas industry, improvements in mining technology are making previously overlooked ore bodies economically attractive. Rapidly developing countries, particularly China and Brazil, are driving demand for iron, copper, nickel, silver, and gold.

With new mines come old concerns about water pollution in the Great Lakes watershed—which in some areas is still recovering from the acid mine drainage, mercury contamination, and sand dumps of past mining booms. Public distrust of international mining corporations and the state officials who regulate them is high.

Because most of the newest mines occur in the wildest places, native communities in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and elsewhere around the globe are fighting to protect their land and water rights, religious sites and cultural resources.

The civic confrontations are influencing mining industry executives and there is growing evidence that mining companies are taking innovative steps to improve their operating standards and reduce political friction. In Mongolia, for example, Rio Tinto supports citizen oversight groups called for by the World Bank, one of the funders of its giant Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine in the South Gobi desert. Still, the actions have largely failed to satisfy opponents concerned about degradation of the environment and sustaining native ways of life.

The Ore Under the River

At the Eagle Mine, pollution fears are founded in the mine’s challenging operating environment. The Salmon Trout River, one of Michigan’s wildest and cleanest waterways, wends its way over the ore body on its journey to Lake Superior. The river cuts through the Yellow Dog Plains near Eagle Rock, an isolated outcrop of wilderness within the mine’s perimeter fence, and a site of great spiritual significance to the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community.

More than 240 meters (800 feet) below the surface, the sheer face of solid ore, smooth and shimmering, breaks through the black bedrock. It is expected to yield 300 million pounds of nickel and 250 million pounds of copper.

The confluence of mineral wealth below ground and important natural and cultural resources above ground is at the root of battles over mining in the U.P. “People ask us, why do you have to mine here?” said Dan Blondeau, communication’s manager for the Eagle Mine. “Well, the fact is, this is where the ore is.”

The ore of the Eagle deposit is among the highest grades in the world, containing up to six percent nickel and four percent copper in some areas. The high grade of the ore initially attracted Rio Tinto, the world’s second largest mining company, to the deposit, despite its small size of approximately 2.4 hectares (6 acres). The company, concerned about soft commodity prices and capacity, shed the mine as part of an asset sell-off earlier this year, transferring the mineral rights to Toronto-based Lundin Mining in July. Lundin has agreed to continue the watershed monitoring program through the Watershed Partnership.

A Legacy of Pollution and Poverty

When Rio Tinto and its local subsidiary, Kennecott Minerals, began exploring the ore body in 2000, it invited nearly equal measures of elation and frustration. In the U.P., a place built on the backs of immigrants working in the mining and logging industries, distrust of big mining companies vies for public priority with broad desire for the jobs they bring. Starting in the 1840s, a mining rush in Michigan’s Copper Country made the region the nation’s leading producer of the metal for 40 years, and iron mining in the Marquette, Menominee and Gogebic ranges also boomed. While there were times of bust, mining remained prominent in the U.P. for more than a century, until the mines began to close for good in the 1960s.

They left behind a legacy of pollution and poverty. Approximately 500 million tons of stamp sands—crushed rock left over after copper ore is processed—were dumped into Lake Superior and its tributaries in the Keweenaw Peninsula. Two sites near Torch Lake are listed under the EPA’s superfund program due to historical copper ore processing. In Negaunee and Ishpeming, entire neighborhoods were moved from so-called “caving grounds” where the earth began to sink over the underground iron mines. Nearby, Deer Lake contends with mercury pollution from the mines.

“My ancestors worked in the mines not because they loved mining, but because they loved heating their houses and buying groceries,” said Alexandra Thebert, executive director of Save the Wild U.P., a grassroots environmental organization opposed to Eagle Mine.

But many of the once booming mine communities in the U.P. and northern Wisconsin, operating with a fraction of their historical populations and downtowns darkened by empty store fronts, are eager for a mining renaissance.

“We say that our greatest export is our children,” said Leslie Kolesar, chairwoman of the Iron County Mining Impact Committee in Montreal, Wis., a small town just over the state border. “My 14-year-old son desperately wants to stay [in the area], but I’m already preparing him to leave because without a mine there are no jobs.”

A proposed open-pit iron ore mine in Iron County could change that. But like the Eagle Mine, it faces a fight from environmentalists, downstream residents, and tribal communities worried about water pollution.

Part of the reporting for this story was done while the author, Codi Kozacek, participated in a fellowship that was paid for by the Institutes for Journalism and Natural Resources.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Excellent article. The caption under the first photo should identify it as the entrance to the Eagle Mine penetrating Eagle Rock. A good overview of mining in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.