Report: U.S. Water Systems, Deteriorated and Slow to Change, Need New Strategy – And Money

More of the same is not working in changed conditions of the 21st century.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

The venerable water utilities of the United States, the essential guardians of public health and enablers of economic growth for more than two centuries, are showing signs of significant wear. A striking new report – arguably the most thorough and candid assessment of the condition of America’s largely publicly owned water transport, supply, and treatment industry – from the Johnson Foundation asserts that U.S. cities and their residents could face water cuts and unreliable service if utilities do not modernize and reinvest.

A blueprint for the future of U.S. water systems, the foundation’s Navigating to New Shores report reflects wisdom gleaned from six years of meetings that were attended by more than 600 analysts, bureaucrats, managers, and researchers working in the still-effective but creaky American water sector.

Written by the respected Wisconsin-based nonprofit environmental foundation, the report describes a lengthening list of ecological risks to water supplies and systems in the 21st century, that – while not entirely new – are nevertheless amplified by the country’s growing population, changing industrial practices, especially in agriculture, and meteorological events that are being magnified by climate change.

“The system certainly needs attention, but we don’t need to rebuild what we had before.”

–Lynn Broaddus, director

Johnson Foundation’s environment program

Water reserves are diminishing in the West. Rainstorms are growing more intense as the planet warms. Waterways that once were nearly scrubbed of pollutants are becoming overloaded with nutrients. These and other indicators – Depression-era distribution pipes and a deluge of new pharmaceutical and chemical contaminants – are evidence that the water-cleaning and water-moving systems that were designed and installed to contend with different conditions generations ago are nearing the end of their design lives. American infrastructure needs to be updated, expanded, redesigned, and, in many cases, reinvented for 21st-century challenges.

U.S. water utilities in countless cities and towns across every region of the nation are, in short, technological anachronisms in need of major makeovers.

In an era of austerity for government spending, and deep cynicism about government’s capacity to solve just these kinds of complex technical challenges, water utilities face enormous challenges to solve the problem that are laid before them, according to the report.

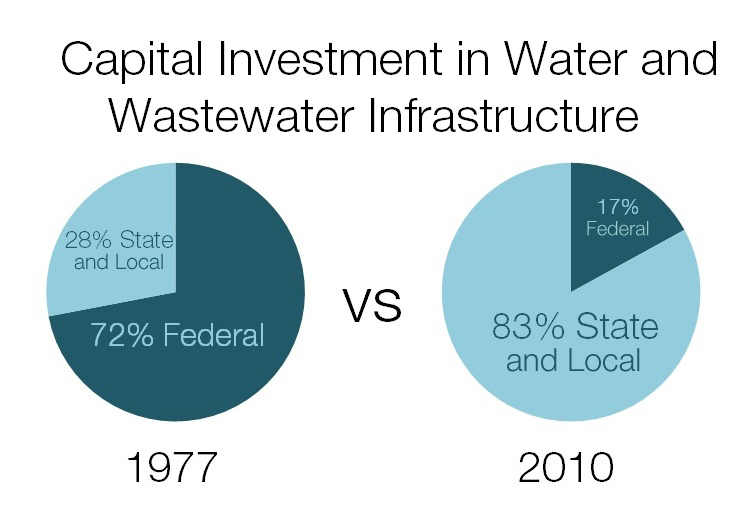

Chief among them is the cost of implementation. And for the time being, most of that expense will be borne by ratepayers. Utilities need to spend $US 633 billion over the next two decades to supply water and to treat sewage, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. For nearly four decades, the federal government – after passing the Clean Water Act in 1972 – has retreated from its role as a leading investor in public water infrastructure.

At one time, during the 1970s and 1980s, the national government footed most of the bill for new sewage treatment plants. Through the construction grants program, U.S. taxpayers provided $US 60 billion for new facilities. At its 1977 peak, more than 70 percent of all capital spending for drinking water and sewage infrastructure came from Washington, D.C., according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Now, the numbers are dramatically flipped.

The grant program was phased out by 1990 and replaced with a smaller loan program. By 2010, the federal government’s share of capital spending for water infrastructure dropped to just one-sixth of total investment, or $US 8 billion. State and local sources contributed $US 38 billion. Including operations and maintenance budgets, state and local agencies account for 95 percent of spending on water infrastructure, according to the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

Dated and In Need of Attention

In search of funds, utilities today face an intractable financial landscape that shows no sign of abating. Austere budgets are the new normal in Washington, D.C. Similarly, states and municipalities, bowing to local political pressures for low rates and cost-cutting, have fallen far short in making necessary investments.

The result is that, in most cases, utilities struggle to keep pace with needs – assuring water supplies, repairing old pipes and equipment, modernizing treatment facilities, installing efficiency and recycling programs and plants. Only one-third of utilities are earning enough revenue to operate sustainable businesses, according to a survey of utility managers conducted by Black & Veatch, an engineering firm. One in five respondents said a doubling of rates over seven years would be necessary to cover costs – a finding that surprised even industry analysts with its magnitude.

The list of operational impediments does not end there. Local governments feel pinched by federal water-quality mandates, a backlog of deferred maintenance, and ratepayer complaints.

And there are only hints of relief. Alternatives to traditional debt financing – from green bonds that spread payments out over a longer time frame to public-private partnerships – are a new discussion. The Obama administration, for one, is encouraging public utilities that are short of cash and loath to borrow to collaborate with private investors. A water resources bill signed by the president in May includes a pilot program to use federal money to spur private investment in water projects.

“Dated and in need of attention,” replied Lynn Broaddus, director of the Johnson Foundation’s environment program, when asked to characterize U.S. water systems. “One of the main points of the report is that the system certainly needs attention, but we don’t need to rebuild what we had before. We need our systems to be more resilient to the times ahead.”

Economists at the International Monetary Fund agree. Since 2006, the perceived quality of U.S. infrastructure – including roads, bridges, and the electrical grid, as well as water – has fallen faster than in any other advanced economy.

The threats are already apparent. More so than any period in recent memory, the consequences of neglect and inaction have revealed themselves in perilous examples of the vulnerabilities of U.S. water supplies:

- In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy knocked large coastal sewage plants offline and caused nearly 42 million cubic meters (11 billion gallons) of sewage to be spilled into waterways.

- In January 2014, a storage tank in West Virginia that held a chemical used in coal production leaked into the Elk River, spilling an estimated 40 cubic meters (10,000 gallons) just upstream of the water intake for Charleston, the state capital. Some 300,000 people were without tap water for at least four days.

- In July 2014, amid the driest 14-year period in the historical record, Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir and a key indicator for water supplies in the American Southwest, dropped to its lowest level since the Great Depression. The seven states in the Colorado River Watershed hurriedly announced new water-saving programs to prop up the Basin’s reservoirs.

- Also in July 2014, a 93-year-old water main ruptured near the University of California, Los Angeles, campus. It fooded the school’s storied basketball court and lost 76,000 cubic meters (20 million gallons) of water during the state’s worst-ever drought. The unexpected lake that formed on posh Sunset Boulevard at rush hour was a visible symbol of a network of water pipes that is past its prime.

- Then in August 2014, strong winds pushed an algal bloom in Lake Erie into the water intake for Toledo, Ohio, shutting down water supplies for nearly 500,000 people for two days.

Scientists and engineers warn that the source of these problems – a changing climate, lax regulation, aging pipe systems – will not soon disappear and some will worsen. To adapt, the report argues, water utilities must rethink their mission, becoming less linear and more circular.

Signs of Progress and Delay

The Johnson Foundation report appears at an auspicious time in the life of the U.S. water business.

Despite the desperate work to match dollars to solutions, the sector offers evidence of vigor and dynamism, Broaddus told Circle of Blue.

Innovative technologies – such as water-cleansing membranes or equipment to remove phosphorus and nitrogen, both ingredients in algal blooms – are appearing with greater frequency. Drought, pollution, and water scarcity have also fostered technological change. The market for reusing water is expanding, particularly in California, which has set ambitious though difficult-to-attain targets for recycled water.

Technological advances are the product of years of research and development. This corner of the business is also seeing new life. Funded by private companies and federal grants, research clusters in Cincinnati, Fresno, and Milwaukee seek to replicate Silicon Valley’s concentration of brain power but for producing irrigation sensors, smart meters, and valves.

The fruits of this labor are finding greater acceptance among utility leaders, because topics that they once regarded as taboo – topics such as green infrastructure and climate change – are no longer passed by. Using wetlands, green roofs, permeable paving, forested open space, and other green-infrastructure practices to clean up water are cheaper than managing pumps and pipes. And in a nation battered by hurricanes that drown major cities, wicked droughts that dry up water for farms and cities, fierce and dangerous storms, and brutal floods, the effects of climate change are visibly apparent, costly, and foolish to ignore.

Examples abound of the new thinking that is being put into practice.

- Philadelphia is investing $US 800 million over 25 years on grassy roofs, streetside buffers that filter rainwater, and wetlands that provide clean-water benefits at a cheaper cost than the traditional menu of pipes, tanks, and other hardware. The goal is to reduce the city’s impervious surface – the pavement and concrete that funnels rain quickly to sewers – by 34 percent, or 39 square kilometers (15 square miles), by 2035.

- The East Bay Municipal Utility District’s wastewater treatment plant in Oakland, California, is a net producer of electricity, saving ratepayers $US 3 million annually in energy bills. Serving 650,000 people, the facility burns methane that is produced from organic waste in the sewage, as well as from food waste sourced from Bay Area farms, restaurants, and wineries.

- The Orange County Water District in southern California is spending $US 143 million to expand its state-of-the-art water-recycling plant, a facility that opened in 2008 and currently provides enough water each year for nearly 600,000 residents. Water from the facility is allowed to filter back into the aquifer that supplies the county with drinking water, thus creating a closed-loop system that has increased water-supply reliability.

- Wichita Falls, a Texas city of 104,000 residents who are suffering from severe drought, recently opened the nation’s first system that connects a water-recycling facility to the drinking water treatment plant for quicker reuse. The urgency is necessary – the city’s main reservoir may go dry by 2016.

Even with this constellation of innovative all-stars, the broader picture is of a sector still stuck in yesterday’s mud.

In 2013, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the country’s dams, drinking water systems, and wastewater plants a D grade, a ranking earned because of inadequate investment.

A New Water Cycle

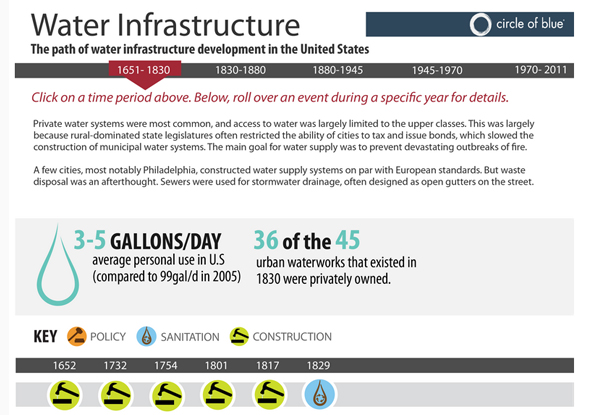

The basic functions of the public water system have not changed much since Philadelphia installed a water works at Fairmount Park in 1812 that even the Europeans – then the world’s champions of urban sanitary engineering – could envy.

Fairmount’s designers would recognize their creation’s contemporary descendents. In most cases, cities still move water as if on straight-line conveyor belts: from river to treatment plant to home, then from home to sewage treatment plant and back to river. When storms drench city streets, the rain is often fast-tracked from gutter to sewer to river, a liquid HOV lane. Worse, many of the pipes that facilitate this procession today should be well into retirement. The average age of a water main in Baltimore, for instance, is 75 years, according to the city’s public works department.

Brittle pipes and rapid removal of rain from city surfaces are hallmarks of the old ways. How, then, should a responsible manager respond? Pipes and treatment facilities will always be part of the equation.

The Johnson Foundation report offers two dozen recommendations for improving the basic model. The recommendations are sorted into five broad categories.

- Be less wasteful with existing water supplies by patching leaks, using efficient fixtures in homes and on farms, and cleaning dirty water for reuse. Like a prudent financial manager, utilities should diversify their sources of supply while charging rates that encourage conservation.

- Build the next generation of wastewater treatment plants. That means employing smaller units in multiple neighborhoods, a strategy of decentralization that will decrease the entire system’s vulnerability to catastrophic events. Next generation also means using grassy sidewalks, roofs, and wetlands to store and filter rainwater and reduce the cost of meeting federal water-pollution standards.

- Bring water, food, and energy systems into closer collaboration. Transfers of water from farm regions to urban centers, as has happened in southern California, is one way to increase municipal supplies without building expensive new pipelines.

- Acknowledge that clean, reliable water is not cheap. Utilities should build support for water-system investment by educating customers about the value of the service, the report argues. They need to raise the price of water and, by charging enough, they will be able to invest in the system, encourage ratepayer conservation, and change the popular take-it-for-granted view that water comes with plentiful supply. It no longer is.

- Create a new utility business model. Utilities will not simply deliver and purify water. They will also take nutrients out of the waste and sell them as fertilizer. They will generate electricity from organic matter in sewage. And they will manage wetlands and forests that double as natural water-storing and water-cleansing systems.

The consequences of not reinvesting and reinventing how America supplies and cleans its fresh water could reverberate from the corner café to big manufacturers, said Michael Orth, senior vice president at Black & Veatch.

“So much of the economy in America is driven by water infrastructure,” Orth told Circle of Blue. “We’ve become so accustomed to these systems being largely reliable. That reliability may drop off, if we don’t reinvest.”

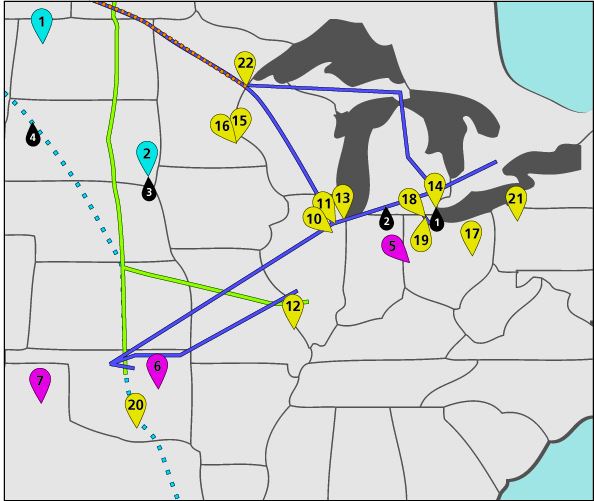

Photo by Scott Strazzante for Circle of Blue’s Choke Point: Index project in the Great Lakes. Graphic by Kaye LaFonde, Circle of Blue’s data reporter. Interactive water infrastructure timeline by Katelin Carter, a graduate of Ball State University’s journalism design program who took an undergraduate course with Circle of Blue.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Comments are closed.