California Drought Puts Old Features in New Perspective

Water for swimming pools, golf courses, car washes at front lines of fresh scrutiny.

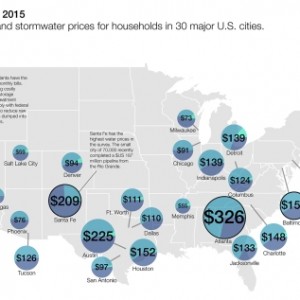

In July, when Santa Barbara’s new drought-influenced water prices go into effect, the cost of filling a typical 28,000-gallon in-ground swimming pool with city water will come to roughly $US 600.

That’s $US 200 more than it would cost under the old pricing schedule. As Santa Barbara homeowners respond to the higher price of water, one more consideration is likely to come into clearer focus: whether to fill the pool at all.

The drying power of a four-year drought is steadily shifting day-to-day expectations, challenging traditional norms, breaking apart business and social conventions, and compelling people in Santa Barbara and across California to confront new ecological conditions so powerful that behaviors thought completely normal and acceptable are now starting to be viewed much differently.

Like filling a swimming pool. The California drought is ending the era of cheap water in Santa Barbara, where water prices are poised to rise 38 percent to 47 percent, depending on how much water is used. More significant, perhaps, than that price hike is how the drought is intensifying competition for water, and fostering changes in how neighbors view each other’s water use.

New Operating Rules

California Governor Jerry Brown earlier this month established the state’s first mandatory restrictions on water use, and called on California residents to cooperate and collaborate in conserving water. It’s not much of a conceptual reach to foresee that homeowners who install new swimming pools, and others who fill existing pools with thousands of gallons of scarce fresh water, would attract attention and invite collective dismay.

It’s also not hard to project how ownership of a private pool in California — a long-standing American totem of wealth and achievement — shapeshifts into a symbol of back-of-the-hand arrogance and selfishness.

Like filling a swimming pool. Click image to enlarge.

The swimming pool, it turns out, is an apt metaphor for California’s big dry. It’s a ubiquitous consumer of water, and a blue lagoon of indulgence on the landscape of a resource-rich state. Until now pools have generally enjoyed solid civic reputations.

There are other drought-related metaphors in transition in California, lots of them. The rifle-straight concrete canals that transport thin streams of water from the depleted snowfields of the Sierra Nevada to the desert south. The unused garden hose that supplied moisture to thirsty lawns and water for scrubbing dirty cars. The sun-splashed expanses of laser-graded vegetable fields no longer showered in the silver threads of irrigation sprinklers. Each image helps to tell a big and complex story of a state that bullied its mountains, forests, rivers, and plains to produce an expensive, water-consuming, resource-intensive way of life that is the envy of the world, and is now itself being bullied by nature.

New Territory For Considering Everything

This is, by no means, play time for California. Every month that passes without rain draws the state deeper into cultural, economic, and public management territory never before explored by Americans or their modern democracy. One outcome is that Californians confronting the day-to-day absence of rain view the regular features of their all-American life in very new ways.

Just like producing food, energy, and shelter, providing access to water is a formative piece of any civilization’s foundation. California’s civilization has expanded in range, and doubled in population since 1970 to 39 million, in part due to the idea that there is sufficient water supply.

The state withdraws 117 million cubic meters (31 billion gallons) of fresh water daily from its rivers, lakes, and aquifers, according to the most recent findings of the U.S. Geological Survey. That’s a lot of water, more than any other state. It equates to roughly the same amount of water that typically pours over Niagara Falls in 14 hours, or the water needs of the Panama Canal over two weeks.

Droughts rearrange the ways that California residents view the relative value of how fresh water is used. The recreational uses come under the first wave of scrutiny.

California’s golf sector, for instance, accounts for $US 6.8 billion in annual economic activity, according to a recent study by SRI International, and encompasses over 1,100 public and private courses. In 2010, golf course superintendents applied 806,000 cubic meters (213 million gallons) of water daily to irrigate 36,826 hectares (91,000 acres), according to the USGS.

That amounts to about half of one percent of California’s daily water use. Yet green golf courses in the desert are visible targets for communities seeking to reduce water consumption.

Urban water consumption — including households, industry, and business — reached 23.8 million cubic meters (6.3 billion gallons) daily in 2010, or a fifth of California’s total water use. Agriculture accounts for much of the rest of fresh water consumption.

Government Reconsidered

Governor Brown’s mandatory restrictions left farmers pretty much alone and focused much of its attention on compelling water savings in homes and businesses. Yet in the weeks following the governor’s first-of-its-kind announcement state government came under modest criticism for letting farmers off the hook even as farmers maintained that agriculture is not an impediment to sound water management but perhaps the foremost practitioner.

People seemed to get the larger point: Guiding California through an unknown number of years of profoundly scarce moisture requires a mix of personal commitment, collective decisions, and investments in water conservation, new storage practices, and recycling. The you’re-on-your-own message that influences so much of the policy discussion in the rest of the country has little resonance in a modern state as dry, or as big and interconnected as California.

The drought is reaching deep into critical but arcane areas of policy and law that are attracting more public attention. State water policy and the federal Endangered Species Act, for instance, are coming under sharper scrutiny. This week, for instance, a California Appellate Court ruled that the practice of charging higher rates for homes and businesses that used the most water violated a 19-year-old amendment to the State Constitution. If the Appeals Court ruling stands, one of the effective financial tools for encouraging water conservation could be lost to cities.

Similarly, the capacity to enforce the provisions of the Endangered Species Act, one of the important legal tools for conserving habitat and fresh water, could dissolve under the concerted legal pressure applied by California farmers seeking more water from the freshwater estuaries between Sacramento and Oakland where one nearly extinct fish, the Delta smelt, cling to life.

It’s not hard to envision the end of the green lawn in southern California, or how the drought could shrink the state’s car wash industry. Local campaigns already have started to discourage car owners from cleaning their cars, like the “Go Dirty for the Drought” project launched by Los Angeles Waterkeeper.

The California drought of the 21st century, in sum, tests the staying power of the features of law, business, and life — like the in-ground swimming pool — that were developed in the 20th century and are so characteristic of America’s most populous state. The drought is an enlightening saga of courage or capitulation, intelligence or intransigence, collaboration or confrontation. It is, in short, sink or swim.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!