The Fall and Potential Rise of California’s San Joaquin Valley

Groundwater pumping is reshaping California’s farm belt.

FRESNO COUNTY, California — Appearances deceive in the San Joaquin Valley. Orange Avenue, for instance, is neither an avenue nor does it have any obvious connection to citrus. It is, in fact, a dirt path in the southwest corner of Fresno County that cuts between an almond orchard to the north and a vineyard to the south and dead ends, in a swirl of dust, at the California Aqueduct.

The aqueduct, for its part, is an artificial river, a concrete canal that moves melted snow from the rivers of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, located several hundred kilometers north, to farms in the valley and cities in Southern California. The aqueduct pulls water uphill and over a mountain on the way to Los Angeles.

An aqueduct that defies gravity. An avenue that is not an avenue. This is the San Joaquin Valley, a segment of the Central Valley, which is an efficiently fertile 725-kilometer (450-mile) garden that produces most of the fruits and nuts that fill American produce aisles. The San Joaquin Valley juggles illusions, perhaps the most important being its attempt to maintain the appearance of hydrological abundance despite its desert environment. Fresno averages just 28 centimeters (11 inches) of rain per year, a bit less than Tucson, Arizona.

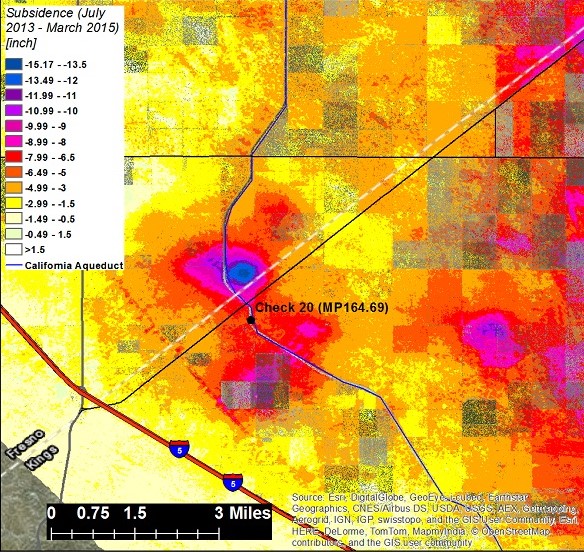

Even the almond orchard and the vineyard are not what they seem: a sturdy investment; terra firma. Except they are not. The soil is unstable; it is shifting underfoot, sinking 20 centimeters (8 inches) in four months last summer, the fastest rate of land subsidence on record for California, according to a NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory study published last month. So much water is being pumped from below ground during this historic drought that the valley floor is collapsing, deflating, like the chest of a dying man whose breaths are ever more shallow.

Subsidence is the technical term for what is happening here: the land giving way as the water that supports it, like air in the lungs, is removed. Despite the headlines, not all of California is sinking. But the patches that are — most of which are in the San Joaquin Valley — indicate that not all is right in the garden of plenty.

The Fall

I park the rental car at the end of Orange Avenue, between the almonds and the grapes and at the base of the 4.5-meter (15-foot) rise that leads to the aqueduct. The late August morning is quiet, the day getting warmer.

This spot, at 36.11 degrees North, 120.06 degrees West, adjacent to Avenal Cutoff Road, is at the edge of a subsidence bowl, one of the deepest to emerge in the Central Valley during the drought.

What should I feel, standing here on unsteady ground? The soil movement — a drop of 5 centimeters (2 inches) per month last summer, at its worst — is geologically rapid but still too slow to notice in person. (NASA used satellite radar to measure the drop.) The slope of the depression is too gentle to attract attention. There are no homes here, no foundations to topple. Only fields, fields, fields…And the aqueduct, which cannot complain if its bones crack. I begin walking between the enumerated rows of almond trees, starting with Row 3.

Instead of feeling, I think. I think about the things that are unseen: the weight of the water that was holding this soil in place. I think about the burden on the rural poor whose wells are dry. More than anything I think about farming’s heavy history of mishaps, degradations, and land revisions in the Central Valley. A few miles east of this spot farmers in the late 19th century began diverting the rivers that fed Tulare Lake, then the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. By the Great Depression they drained so much water to grow cotton and other crops that Tulare Lake and its wetlands disappeared, now only fossils on yellowed maps.

There are other subsidence hot spots in the Central Valley. One is centered near the town of Corcoran, where California’s high-speed rail line, now under construction, will pass. State officials told me that they “do not think it will be a huge deterrent” to the $US 68 billion project. Another zone of concern is near El Nido, 160 kilometers (100 miles) to the north.

The subsidence does not have to be large to cause problems for bridges, canals, and roads, according to Claudia Faunt, a U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist. It only has to be in the wrong spot, just enough displacement to upset the engineered balance. For instance, managers had trouble moving water through the Delta-Mendota canal last summer because a dimple of sinking land threw off the canal’s slope.

The Rise

I hear rain.

Impossible, I think, seeing the cloudless sky. But the sound is unmistakable. Soon I see the source: a drip irrigation line at the base of an almond tree. The thin black line is punctured, shooting water several meters into the air.

Drip lines run the length of Row 3 and of all the other rows, giving the trees sips of water at ground level. Circles of moisture, like a sweat stain, mark the base of each tree, each circle ringed by a fringe of salt.

Blaming the farmers for all the valley’s ills is the easy accusation. And it is approximately true. Collectively they have pumped enough water to deform the land at a rate faster than at any time on record. But start walking back through the chain of causation and the effects blur.

Farmers pump because they received little to no canal water this year or last. Water from Northern California halted an earlier subsidence crisis in the 1950s and 1960s, but that solution — import more water — is no longer feasible because the donor ecosystem, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, is suffering from inadequate supplies. Farmers pump because they planted almonds and pistachios, grapes and pomegranates, perennial crops that need water every year to survive and are less resilient to extended droughts than land that can be fallowed. But they are also lucrative crops that people pay a premium to eat. Farmers pump because they are allowed to. Only last September did California pass legislation that requires groundwater basins to be managed sustainably.

What goes up must come down, but what about the land that sinks down? Must it come up again? The groundwater law requires that water use in these critical basins be in balance by 2040. That means that farm districts must think just as hard about getting water back into the ground as they do pumping it out. Most of the subsidence, however, is permanent, according to Claudia Faunt. Aquifers made of sand and gravel are more resilient to a loss of water. Those of clay tend to smush together when the water is drained from them, which is happening now in the subsidence zones. When they are compacted, the clay layers no longer store water. Faunt told me that the amount of storage capacity lost in the Central Valley as result of subsidence is “substantial.” The key tactic in the future will be to add water before the land begins to settle.

What you see in the Central Valley is not what was once seen. The lakes and wetlands are greatly diminished. The rivers diverted. The land scraped flat. The drought today is changing the valley. California’s 20th-century network of long-distance water transfers is becoming less reliable as the Sierra Nevada snowpack that feeds it ebbs. The state’s densely packed farm economy will most likely irrigate fewer acres. The illusion of abundant water is being dismantled, bit by bit. But what shape the valley will take next is still to be written.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!