Panama’s Water-Rich Eden Confronts Snake’s Temptation

Can the richest Central American nation build a commercial eco-paradise?

PANAMA CITY, Panama — Quebrada Ancha, a community that settled in Panama’s thick forest 50 years ago, lies at the northern end of Lago Alajuela, a freshwater lake built by the United States at the end of the Great Depression to control floods in the Panama Canal Zone.

It takes 20 minutes in a fast 40-foot dugout boat to get there. In early morning’s luminous light and cooling breeze the trip is a passage across a water-rich green paradise. Fish eagles dive for tilapia. Hummingbirds swarm in the tangled branches of small trees. Grapefruits and oranges, papayas and mangos, coconuts and bananas ripen in a geography of wild bounty.

The long path through the forest to the community’s center is like striding down a tropical produce section. Sugarcane and ginger and breadfruit, pineapple and marañon Curaçao, which looks like an apple and tastes like a pear, grow abundantly in the forest. Honey is collected from wild bees that nest in the village’s hives. Fresh fish is abundant.

A number of Quebrada Ancha’s adults were children when they arrived in 1976 with their families from central Panama; they were refugees forced out of their homes by the backwaters of the 260-megawatt Bayano Dam. Quebrada Ancha’s phenomenal natural riches now support about 100 adults and children, and attract foreigners who visit with increasing frequency.

Coffee, Not Forest Clearing

In a shift that is representative of Panama itself, the residents of Quebrada Ancha see in their largely unspoiled territory potentially useful new ways to thrive in the 21st century.

For instance, instead of burning forests for new farm lands, a practice that drains nutrients from the soil, the village cultivates shaded and permanent hillside plots. In some they raise coffee bushes that in 2014 produced 75,000 pounds of coffee beans for sale to roasters in Panama City, the capital, about an hour away. A portion of the harvest also is dried in the sun, roasted over open fires, and available in the village for $US 9 a pound. Quebrada Ancha’s location, set amid a grove of shade trees on a high bank above the lake, is a delightful perch for savoring the strong and delicious village brand.

Quebrada Ancha is completely surrounded by the 131,000-hectare (505-square-mile) Chagres National Park, where over 50 species of birds live. The 30-year-old park serves as a buffer zone to store clean water for Panama City and to supply water to the Panama Canal’s six locks. Its rainforest and mountainous landscape is wild enough for roaming jaguars.

Adrián Chang, a staff member of the Fundacion Parque Nacional Chagres, a nonprofit that aids in the park’s management, said there are 33 other villages and 3,400 more people within the park’s boundaries. Residents serve as a wholly necessary volunteer squadron of rangers to keep poachers and unlawful activities at bay. “With these people,” Chang told me, “we have more eyes, more ears, more people to keep bad things from happening.”

Chang’s words are almost an article of faith in Panama. I am here for all of January to expand Circle of Blue’s frontline reporting on energy, water, and food to Central America. My interest is understanding the remarkable opportunities that could lie ahead for this magnificent country of such ample beauty, water, and forest ecology. Or what bad things could unfold due to poor management.

Over the next month or so Circle of Blue will post reports on:

- The effects on world trade in energy and agriculture from the roughly $US 6 billion expansion of the Panama Canal, which is scheduled to open for business in April 2016.

- Rising demand for energy in Panama that is leading to aggressive proposals for hydropower, and thermal power plants possibly fueled by coal, which has been sparingly used for power to date.

- The confrontation over water and energy stirred by a huge copper mine planned for Panama’s Caribbean coast.

Challenges for a Commercial Eco-Paradise

What I’ve discovered is that the richest nation in Central America is well aware of the challenges. It’s also making big choices about its economy and identity. The early indications are that Panama is intent on building a kind of commercial eco-paradise, one that instills the principles of resource conservation that has served Costa Rica so well, but also establishes the contemporary trade, communications, transport, office, housing, energy, and water infrastructure that fits a nation that operates one of the world’s important maritime centers.

In essence, Panama is a big experiment. It’s held off the drug trade that turned its neighbors — El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras — into murder centers. It seems intent on snuffing out corruption that hampers government and makes its citizens cynical.

Panama also has money to invest in nation-building, most of it earned legitimately. In October the BioMuseo opened in Panama City, home to 1.5 million people. The museum is a $US 100 million, 44,000-square-foot center of ecological education designed by Frank Gehry. In April, the first 8.5-mile, 12-station line of the $US 1.5 billion Panama Metro opened. It’s the first subway in Central America and already carries 150,000 passengers daily.

Since January 1, 2000, when Panama gained full control and ownership of the Panama Canal, annual economic growth has averaged almost 10 percent. The multi-level summits of Panama City’s soaring white office and residential skyscrapers are like a seaside chart of international interest and investment.

Birth rates are comparatively low. It took 30 years, from 1950 to 1980, for the country’s population to double from 1 million to 2 million. It will take 40 years, from 1980 to 2020, for Panama to double again to 4 million residents.

Big Promise in a Thinking Country

While not large, Panama isn’t terribly small either. It’s about the same size as Belgium and the Netherlands. Summed up — there’s a lot of wild jungle, clean water, and natural shoreline in Panama that is in pristine condition. So much ground is untouched that biologists and ecologists regularly discover new species in Panama.

The challenge for Panamanians and their leadership is how to use that bionomic bank account in the 21st century. Quebrada Ancha community sees itself as part of the answer.

Not long ago, Quebrada Ancha built a community center — an open-air pavilion with a palm-thatched roof, a concrete floor, and an adjoining kitchen with a wood-fired stove. Along with an open-air Catholic sanctuary, a school, and a grouping of big tanks on a mountainside that provide homes with gravity-fed fresh water, the center is a choice piece of community infrastructure that provides a public good — and not only for the village.

Tourist Trade in Quebrada Ancha

During the last year, Quebrada Ancha has used the center to host groups of visitors to share in the village’s culture, to observe its flora and fauna, and to eat a satisfying meal. There is no posted charge. Adrián Chang quietly suggested a donation/fee of $US 20 per person.

Jaime Figueroa, a former IBM executive who now is a specialist in tourism and development in Panama City, has opened a lot of doors here for Circle of Blue. He made the arrangements for the Quebrada Ancha visit. The day Jaime took us to Lago Alajuela, Quebrada Ancha’s community cook served a lovely lunch of fried tilapia, fried plantain, ginger ale made from home grown ginger, and coffee sweetened with home grown honey.

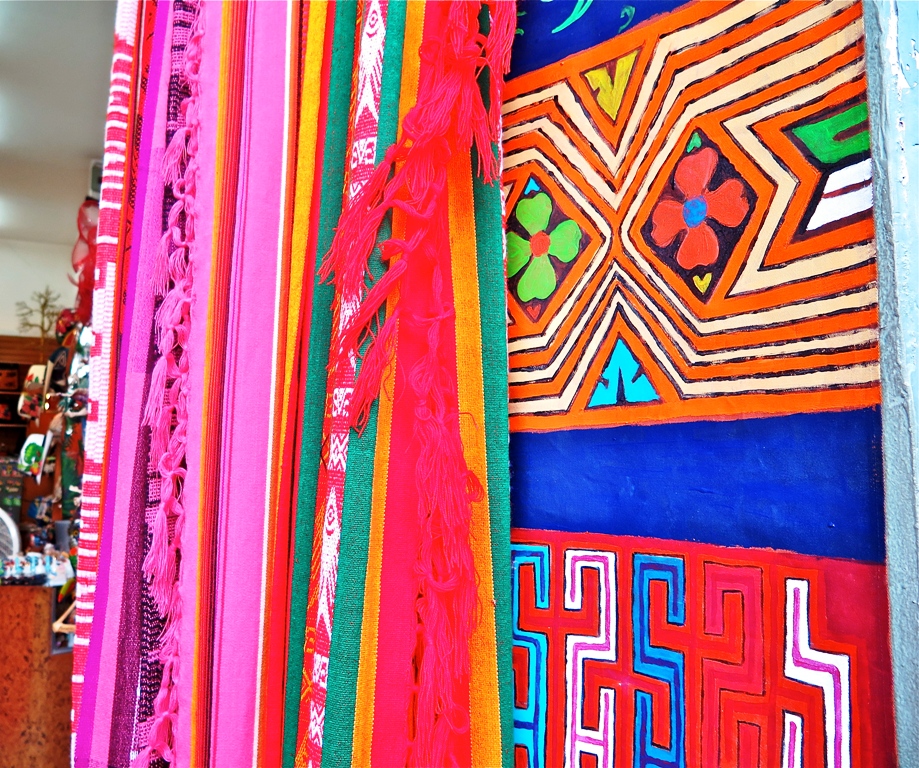

The entire village is involved with its new tourism business, which hosted 42 visits and 700 visitors during the past year, said Agustín Núñez, a 46-year-old resident and village leader. The highlight of the day was the gorgeous village children, boys and girls dressed in colorful native costumes, who greeted us on arrival. Later they performed folk dances and a play about protecting the land and water that they wrote with the help of a teacher.

There was time in the afternoon to share ideas. I learned that Quebrada Ancha’s residents didn’t pay much attention to Panama’s military dictators, who ruled for 22 years until an American invasion ended the grim period late in 1989. With no electricity, and living far removed from the mainstream, the police and army didn’t pay any attention to Quebrada Ancha, said Molinar Toribio, a 47-year-old resident.

Toribio and his friends learned from me a little about the global contest for energy, water, and food, and a little more about a small and capable newsroom of the future based in northern Michigan that cares what happens to regular people in interesting places like Quebrada Ancha.

— Keith Schneider, senior editor

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!