Surviving the Nepal Earthquake

Circle of Blue intern Crystal Edmunds recounts her first-hand experience of the Gorkha earthquake and raises questions about what it means for water.

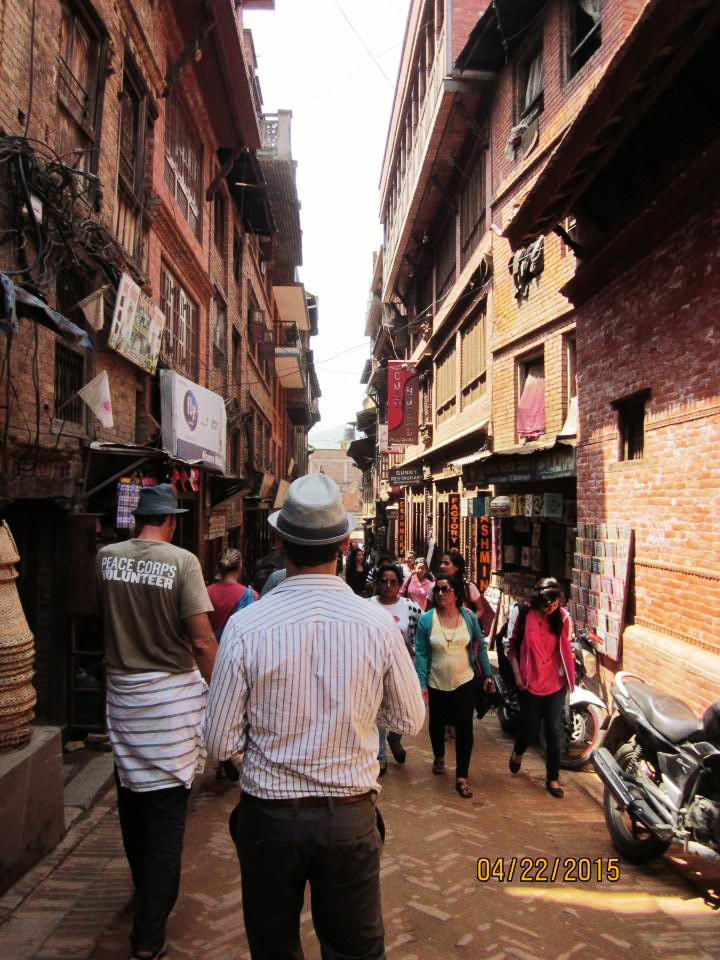

THAMEL, Nepal — Just before noon on April 25, I had just stepped out of the Israeli-run OR2K restaurant in Thamel, a part of Kathmandu, Nepal, where the buildings pack together like sardines in a can. My Peace Corps training group of 33 volunteers had been visiting Kathmandu for a few days, and we were scheduled to return to our training village, located 30 miles southeast of the capital, at 1 p.m. local time.

We had recently discovered another part of Thamel — an alleyway off of an alleyway, complete with a coffee shop, yoga studio, rock shops, and a bohemian Middle Eastern restaurant — and were immensely thankful for a change in our routine diet of rice and lentils, not to mention being surrounded by hippie travelers from around the globe. I was on what we called a “Peace Corps high.”

We were quickly brought back to earth as the ground started to roar, pulsing up and down and shaking so violently that I’m still not sure if what I saw was an optical illusion. I ducked and fell into the closest ground-level shop with one of my fellow volunteers, waiting out the next minute and a half for the buildings around us to fall and for our lungs to catch their final breath. While the others around us cried, my hilariously mellow friend tried to feed me ice cream to calm me down. (I actually laughed, but didn’t eat any ice cream.) All I could think was that this was “The Big One,” the massive earthquake that this country had been dreading for decades.

While the earthquake was devastating, it wasn’t “The Big One.” The Earth showed us mercy.

The earthquake registered a magnitude of 7.9 and shattered portions of Nepal. The death count now hovers around 9,000, with 6.6 million affected in the greater region. I only saw a minute fraction of the devastated buildings, roads, and infrastructure.

As of June 8, the Ministry of Home Affairs confirmed more than 505,000 houses were destroyed and almost 279,000 damaged. While official government sources indicate that there are no internally displaced people, the International Organization for Migration’s Displacement Tracking Matrix recorded a total of 3,537 households (21,610 people) in 64 displacement sites in Bhaktapur, Kathmandu, and Lalitpur districts as of May 21.

I had been in Nepal only two months, training to serve as an agriculture extension volunteer for the Peace Corps — my “holy grail” for years before I started the Masters International program at the University of Denver in 2009, where I am currently enrolled. Ever since spending a summer in India that sent me into a philosophical tailspin, I had longed to return to South Asia. So when the Peace Corps offered Ethiopia, Nepal, and SEnegal as options for placement, I immediately chose Nepal.

Growing up on the banks of the Maumee River in the Ohio flatlands, one constant in my life has been the stability of the Earth. When weighing the potential safety hazards of Ethiopia, Nepal, and Senegal, threats of Ebola, terrorism, and malaria came to mind. But seismic activity? Never.

During the initial Peace Corps orientation in Kathmandu our first week in Nepal, the security officer gave a presentation about Nepal’s earthquake risks. With a history of 10 large events occurring within 679 years, the country expects a major earthquake around every 70 years. The last significant quake hit in 1934, meaning that the country was 11 years overdue for another event. Forecasts estimated that an earthquake of magnitude 7.0 or higher would result in 25,000 to 40,000 immediate deaths and a liquefied airport.

Yet, between studying Nepali, learning the foundations of Himalayan permaculture, and the dhal bhat food comas, the potential of a looming catastrophe dissolve away for me.

We were told that Kathmandu would be one of the worst hit places in the country due to its sedimentary rock foundation, which amplifies seismic waves, and its enormous population that had swelled due to the recent civil war — a thought that immediately came rushing back to me in that interminable minute in Thamel.

But the building I was sheltered under did not fall.

As soon as the roaring stopped, we made our way out of Thamel and toward the rest of our group. We slowly traveled to an open field where we waited out the aftershocks for about five hours, until the Peace Corps staff moved us to the American Mission in Nepal and then to the U.S. Embassy. I spent a week in the embassy, studying seismology, Haiti, and Pakistan, while also assisting the embassy with the more than 300 Americans who sheltered there. I was too scared to leave the fortress that is the embassy as aftershocks continued to shake the earth and crumble the already compromised buildings around us.

After a week in the safest building in Nepal, we flew to a debriefing in Thailand, then home.

The Peace Corps is returning to Nepal on June 20 to work in the health, food-security, and sanitation fields. I have chosen not to return, instead interning for the summer in Circle of Blue’s seismically-inactive Traverse City office and pursuing a Peace Corps transfer to Armenia in a few months.

I may have survived the quake, but Nepal’s active fault lines are exposing vulnerabilities that the country is simply not equipped to endure — many of which are related to its unpredictable environmental assets. I hope to share the stories of my colleagues who are on the ground in Nepal and begin to address questions such as:

1. The approaching monsoon will likely exacerbate the humanitarian crisis in Nepal. Is there any way to mitigate its effects?

Seismic activity could lead to more severe and increased glacial outburst floods (GLOFs) — a type of flood that occurs when the natural ice dam containing a glacial lake fails — with devastating effects downstream. A majority of the hill and mountain slopes in the quake-hit districts are unstable and weakened due to earthquakes and frequent aftershocks, making them highly vulnerable to landslides, triggered by heavy rains. Moreover, the monsoon could slow aid efforts by 50 percent, according to aid organization Shelterbox.

2. How can the international community assist Nepal more wisely and efficiently than Haiti?

The 7.0 magnitude earthquake in Haiti that killed 220,000 people highlighted the shortfalls of the international aid process. More than $US 10 billion in foreign aid still hasn’t enabled Haiti to recover from the disaster. Further, a cholera outbreak infected more than 700,000 people and killed 8,646, according to the World Health Organization. In monsoon-drenched Nepal, flooding equates to major sanitation issues and could foster outbreaks of water-borne diseases.

3. What does the earthquake mean for hydropower?

In my brief tenure in Nepal, I was constantly reminded of its water wealth. My host family, language teachers, and the Nepalis I would meet on a day-to-day basis were all very proud of Nepal’s standing as one of the world’s most water-rich nations. They also discussed how Nepal is not utilizing its resource potential. The earthquake caused widespread damages to the country’s hydropower infrastructure, as Circle of Blue has reported. These damages could create more dependence on Nepal’s hydropower developers, particularly China and India, perhaps aggravating its political instability.

4.How will the earthquake affect the political instability of Nepal?

Leaders from Nepal’s major political parties have signed a 16-point agreement to resolve the key contentious issues of a new constitution, The Nepali Times reported. The agreement comes nine years after the end of the country’s civil war, which was led by a Maoist insurgency. Political developments will be important to follow, particularly because the Maoists want to curb foreign involvement in the development of Nepal’s natural resources.

Did you experience the Nepal earthquake? What do you think this disaster means for water? I would love to hear your stories and ideas. Send me a tweet at @ce301005, email me at ce301005@ohio.edu, or comment below.

–Crystal Edmunds, Circle of Blue intern

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!