Atomic Crumbs Guide First Global Assessment of Groundwater Age

Newer groundwater is a small fraction of total reserves

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

The fallout from a major 20th century threat is helping scientists understand the dimensions of a significant new challenge in the 21st.

By analyzing isotopes of tritium, an atomic variant of hydrogen that accumulated in lands and waters after the dawn of the nuclear age, a group of researchers was able to produce the first global estimate of the age of groundwater. The results show that groundwater, which provides two-fifths of the water used for world agriculture, is not inexhaustible.

Between 1 percent and 17 percent of the water stored in the first two kilometers of the Earth’s crust is less than 50 years old, according to the study published today online in the journal Nature Geoscience. The best guess is that 5.6 percent of the world’s groundwater is of this “modern” variety.

Determining the amount of modern groundwater is a useful exercise, said Tom Gleeson, the study’s lead author. The newest reserves are the most susceptible to contamination from contemporary agriculture, industry, or energy extraction. Being nearest the surface they are also most accessible. Tapping older stocks, which may be saturated with salts or metals, indicates that groundwater demand out of balance with local supply. As the tritium analysis reveals, most groundwater was deposited centuries or millennia ago.

“The results show that young groundwater is a finite resource,” Gleeson, an assistant professor at the University of Victoria, told Circle of Blue.

The age dating study is part of a growing body of research that is revealing how vulnerable the world’s food and energy production is to groundwater depletion, drought, and mismanagement. A study published in June, for instance, used satellite data to show that water storage in 21 of the world’s 37 major aquifers had declined since 2003. Water levels in many California wells have plunged to record lows in the fourth year of a historic drought.

A Step in Assessing Groundwater Sustainability

The study affirms intuitive hunches about groundwater age. The youngest groundwater is found in tropical areas and mountain regions — the Amazon, Andes, and Congo — that receive a consistent cycle of moisture. There is less modern groundwater in arid regions such as the Sahara and Gobi deserts, the North American plains, and Australia.

The researchers used other methods to check their work. In addition to the tritium analysis, they calculated groundwater ages pairing hydrological models with data on water tables, recharge rates, and the sponginess of the land. These data sets each showed different age distributions — more modern groundwater in mountainous regions in one data set than in others, for instance — but they generally agreed on the total amount. In other words, it is likely that there is relatively little modern groundwater stored in the Earth’s crust compared with reserves that were deposited before the Roman Empire.

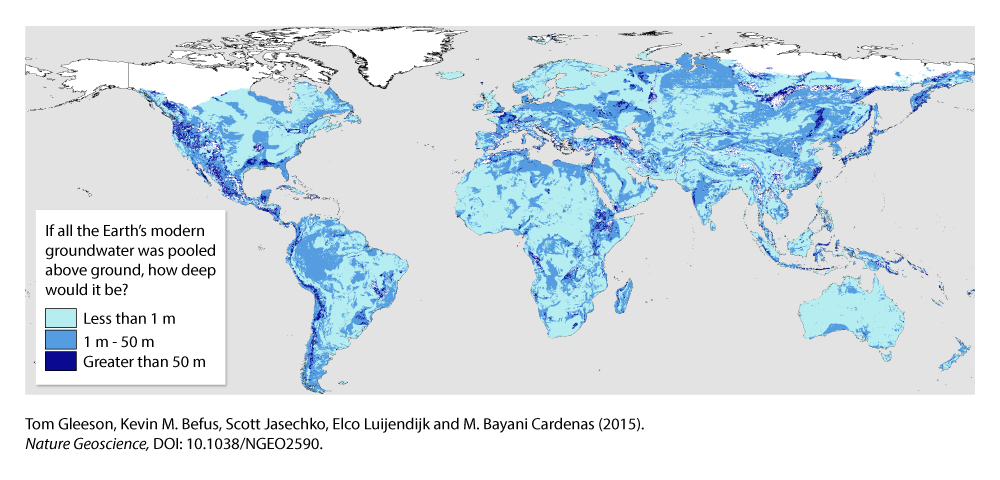

Spread evenly, modern groundwater would cover the land to a depth of 3 meters (10 feet), or the height of a basketball goal, according to the study. Total groundwater reserves would flood the Earth in 180 meters (590 feet) of water.

The age dating study is part of a series of assessments that will examine the sustainability of groundwater use, Gleeson said. Next, he will compare rates of groundwater use and extraction with the results of this study. That combination of data will produce maps showing those areas that are withdrawing modern groundwater faster than it is replenished — where water users are, in effect, mining the resource. This is happening today in the American Great Plains where the Ogallala Aquifer, the largest source of underground fresh water in the United States, is being depleted to grow cotton, corn, soybeans, and wheat.

To be of use to local water managers, however, the age analysis needs to be run at a finer scale. Gleeson said the maps in the age dating study reveal the big picture and are useful for guiding national water policy rather than for individual decisions.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!