Australia Coal Mines Prompt Concerns about Groundwater and Climate

Mining Queensland’s ample coal seams will require a lot of groundwater — and lead to more carbon pollution.

A view over an open-cut coal mine in Australia’s Hunter Valley in New South Wales. Coal companies are eyeing the development of coal deposits in the Galilee Basin in Queensland. Photo © Aaron Jaffe / Circle of Blue

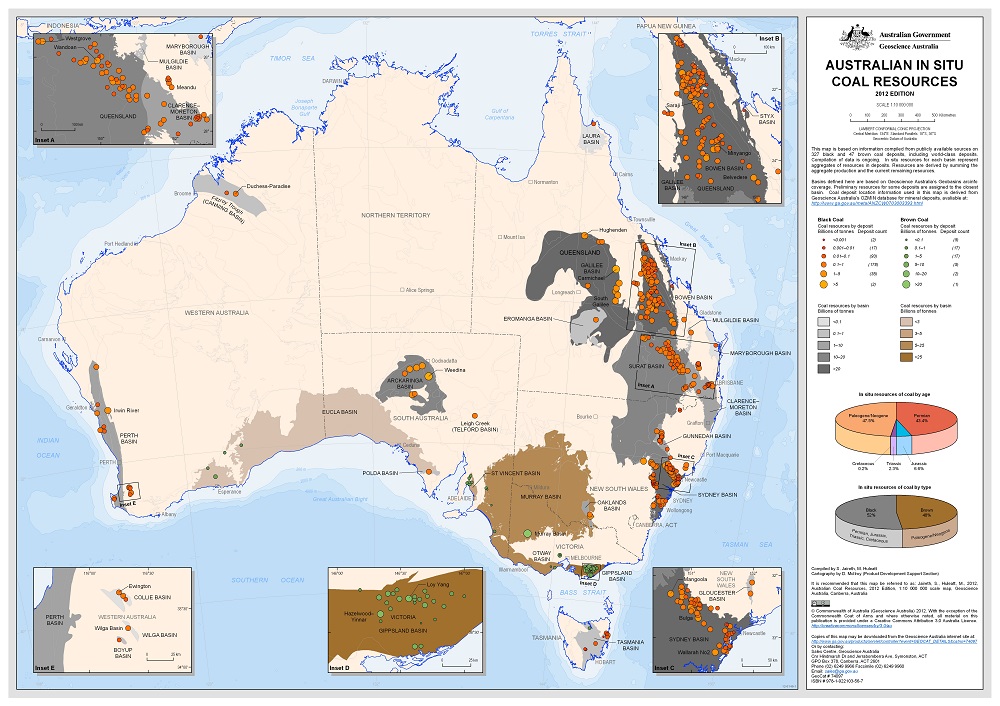

Coal companies have pegged Queensland’s Galilee Basin, a geological formation in the state’s interior, as the next big production zone for Australia’s coal mining industry as it looks to increase exports to India, China, and other Asian economies.

Though the federal government keeps endorsing new projects, opening the mines will be difficult. The industry faces economic headwinds as the world begins to turn its back on coal as a fuel source. There are also public fears about the mines’ water use. Two events in the last month show why water resources are an impediment.

On October 30, the Land Court of Queensland heard final arguments in a legal challenge against the $US 3 billion Kevin’s Corner coal mine, located in the Galilee Basin. Conservation groups and a rancher contend that the mine, approved in 2013, will wreck the area’s groundwater reserves.

“To date we’ve been given no security at all that our groundwater supplies won’t be destroyed by the impact of those mines,” Bruce Currie, the rancher, told ABC news after the first day of the two-week hearing.

Two weeks earlier, Greg Hunt, Australia’s environment minister, authorized the $US 11.9 billion Carmichael coal mine, also in the Galilee Basin. When — some say if — it begins operation, Carmichael will be the country’s largest coal development, producing as much as 60 million metric tons per year for export.

Carmichael, also being challenged in the Land Court, is the fourth large coal mine in the Galilee Basin approved by the Queensland government since 2012. A fifth mine is undergoing an environmental review. Combined, the mines will impose new strains on the ecology of a region prone to deep droughts and torrential floods.

Groundwater Supplies at Risk

Clawing carbon rock from the earth at Carmichael will require significant volumes of water — some 12.5 billion liters (3.3 billion gallons) per year, according to Adani, the Indian company behind the proposal.

Hunt, the environment minister, acknowledged in 2013 during the review process that the mine would deplete groundwater reserves, cause land subsidence, reduce the flow of the Carmichael River, which bisects the site, and diminish the Doongmabulla and Mellaluka springs complexes, home to the endangered black-throated finch, Yakka skink, blue devil, and other threatened species.

Based on the recommendations of an independent scientific panel that assessed the Carmichael mine in 2013, Hunt imposed 36 conditions on the mine as part of its approval. He required that Adani set aside 38,000 hectares (93,900 acres) of critical habitat for species conservation and submit at least three months before beginning excavation a groundwater management plan and a plan for researching and avoiding damage to the springs. He also set limits on the drawdown of the springs and required a regional groundwater model as a condition of approval. The panel had criticized the government for not assessing the cumulative effect on groundwater of all the mine proposals in the Galilee Basin.

“The rigorous conditions will protect threatened species and provide long-term benefits for the environment through the development of an offset package,” Hunt said in a statement on October 15. “These measures must be approved by myself before mining can start.”

Hunt did take into account the scientific panel’s recommendations, according to Matthew Currell, who studies groundwater at RMIT University in Melbourne, but the groundwater modeling process is a bit backward.

“At this stage the model can’t be populated with much actual data from the various proposed mine sites, as most of the monitoring would commence only after mine construction begins,” Currell wrote in an email to Circle of Blue. “This is a bit of a paradox, because until the data comes in, the predictions the model makes of future impacts probably won’t be very accurate.”

Other legal challenges await Adani. Like Currie, the rancher, aboriginal groups in the Galilee Basin object to new coal mines. The Wangan and Jagalingou people strongly oppose the Carmichael project, claiming that it will destroy the springs and leave a “huge black hole” in their homelands.

Hunt noted in his statement of approval the potential damage to ecosystems and said that he “considered all relevant new information.”

“What this means in practical terms is anyone’s guess,” Currell wrote. “In essence I believe he is saying ‘I have considered your concerns and I choose to ignore them’. Expect further court challenges, as the traditional owners continue to argue that they have the right to refuse consent to mine on their ancestral lands.”

Coal Expansion Faces Other Headwinds

Water is not the only obstacle for new mines. Some opponents are concerned that wastewater and the burning of the coal will damage the Great Barrier Reef, some 300 kilometers (186 miles) away. Those skeptical that the mine will ever break ground point to the industry’s increasingly sour economic picture, which is due to steep costs, declining prices, and more vigorous action to address carbon pollution.

The costs of developing the Galilee Basin, where coal deposits are hundreds of kilometers from the coast and without transport infrastructure, are significant. Huge capital investments will be needed to open the mines, build rail lines, and expand port facilities. The Carmichael mine is a $US 11.9 billion package that includes a 189-kilometer (117-mile) rail line. Fourteen banks have declined to finance the project, according to the Sydney Morning Herald.

Meanwhile, the industry is struggling financially. Total income in Australia’s coal industry dropped 24 percent from 2012 to 2014, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Worse, the industry as a whole was not profitable in 2014, marking a $US 937 million loss as the price of coal on the spot market fell to less than half its 2011 peak. The industry is already seeing casualties. The $US 8.6 billion Dudgeon Point coal export terminal was cancelled by North Queensland Bulk Ports, the developer, in June 2014.

Critics also note that the world, albeit slowly and incrementally, is beginning to turn away from coal. In the run-up to the United Nations’ climate summit in Paris in December, 155 countries have submitted pledges to cut carbon pollution. Australia’s pledge was rated “inadequate,” according to Climate Action Tracker, a science group that is analyzing the effectiveness of each country’s plan.

That rating is based on backsliding in Australia’s domestic energy policies, including a repeal of a budding carbon pricing scheme in July 2014 and slashing the national renewable energy target by 20 percent in June 2015.

Government analysis of the Carmichael mine did not consider the carbon pollution from burning the coal, most of which will be exported and would not register in Australia’s domestic carbon accounting. This is shortsighted, argues Samantha Hepburn, a professor at Deakin University Law School.

“Knowing what we do about the imperatives of climate change, approving a vast new coal plant on the eve of the Paris climate change talks, in complete disregard of its significant greenhouse gas implications, is unethical and, at a global level, indefensible,” she wrote in The Conversation, an online forum for policy and scientific analysis.

The irony, of course, is that Australia, already hot and dry, will become much hotter and drier if carbon emissions continue to soar.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!