California Drought: A Dry January Closes and Dread Mounts

Snowpack in the parched state is just 25 percent of normal, a near-record low.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

It’s not a worst-case scenario — at least not yet. But the optimism that sprouted in California after a drenching December is wilting at winter’s midpoint. State and federal officials are again preparing for a year of unpleasant decisions that will test the state’s ability to manage a severe social and ecological crisis.

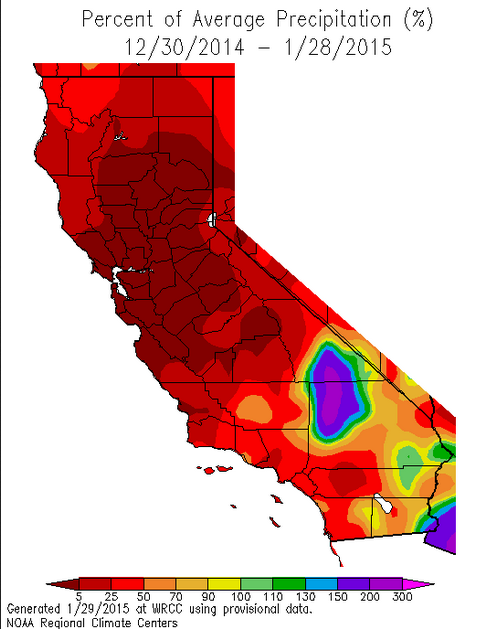

All hydrological signs indicate that 2015 will be a tougher challenge. California received almost no precipitation in January, typically the wettest month. Temperatures soared to as much as 8 degrees Fahrenheit above average in the Sierra Nevada mountain range, accelerating the melting of snow that fell in December.

–Arthur Hinojosa, chief of hydrology

California Department of Water Resources

Measurements taken on Thursday revealed that snow levels at the Department of Water Resources’ official monitoring site some 145 kilometers (90 miles) east of Sacramento are just 12 percent of normal, or “dismally meager,” according to the department. Measurements from a broader network of sensors suggest that the snowpack in all regions of the Sierra Nevada is just 25 percent of normal — an enormous drop from the December assessment, which was 50 percent of normal. A bleak midwinter indeed.

“It’s a bit grim,” Arthur Hinojosa, chief of hydrology at the California Department of Water Resources, told Circle of Blue. “It doesn’t bode well for the coming year. Even average precipitation for February and March would do little to alleviate the pain.”

Preparation For Less Water

Water managers are preparing for another drought year. Their task is unenviable: divide scarce water supplies between cities and farms, wildlife refuges and rivers, for a system that is in the midst of a massive environmental shock. A dreadful 2014, the state’s hottest and third-driest year, taught officials not to delay.

“In 2014 we learned the value of early planning, cooperation, and communication,” said Tom Howard, executive director of the State Water Resources Control Board, which administers water rights. Governor Jerry Brown, a Democrat, declared a drought emergency on January 17, 2014, and organized a drought task force comprised of agency officials that meets weekly.

The fruits of early planning are beginning to show. Managers from the State Water Project and the Central Valley Project, the two major dam-and-canal systems that move water hundreds of miles from north to south, released a drought plan on January 15, a full three months earlier than last year. The blueprint for disaster response prioritizes three areas: supplying water for human health and safety; pushing saltwater out of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the crossroads for water supplies being pumped across the state; and maintaining enough cold water in mountain reservoirs to dampen river temperatures during the late summer salmon runs.

Juggling the three, in addition to doling out supplies to dozens of farm districts and municipal systems from Sacramento to San Diego, will require a deft touch.

“We have to figure out the most critical areas and operate as close to the edge to balance available supply with demand,” Howard told Circle of Blue. “A lot of people won’t get the water they feel they need. There is water that won’t get delivered to the environment as well.”

The State Water Project announced in January that its 29 contractors — mostly farm districts and cities in the Bay Area, Central Valley, and Southern California — would receive 15 percent of the water they requested, an allocation that seems unlikely to rise given the pitiful snowpack and reservoirs that are no better off than last year. Though storage is up slightly in Lake Oroville, the main reservoir for state canals, six key reservoirs operated by the federal Bureau of Reclamation collectively hold less water than in 2014, by a few percentage points.

New Water Restrictions

Signs of stress in the system are appearing. On January 23, the water board told water rights holders to prepare for restrictions. Last year was the first time since 1977 that the board had invoked curtailment, a process in which those who acquired their rights most recently were told that they could not draw water from a river. The board will post a list of critical basins in the next few days, to help communities who might be cut off to plan for alternate sources.

The state’s largest water wholesaler is also considering restrictions. Reservoir storage for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California dropped by more than half since 2012. The district, which supplies half of California’s 38 million people, will decide in the next six to eight weeks whether to cut supplies to its retail contractors by 10 percent, according to Jeff Kightlinger, the general manager.

Elsewhere, problems that became acute in 2014 risk turning endemic. Farmers in the San Joaquin Valley will receive a fraction of their surface water supplies, forcing many to pump more groundwater to reap a harvest. The same circumstances last year led to a public health crisis in Tulare County, a farm county the size of Connecticut, as dry domestic wells left thousands of residents without running water.

“It’s looking worse this year in the San Joaquin Valley,” Hinojosa said. “The problems will be exacerbated. There will be more communities with more troubles.”

Fish Without Water

Though urban users will struggle, fish will be devastated unless more snow falls. A fish survey conducted by the Department of Water Resources in December found a record low number of Delta smelt, an endangered species protect by federal law. The department is considering installing emergency dams in the delta if water supplies do not improve. The dams would channel freshwater to force back an infiltration of salty water that threatens fish, farms, and drinking water intakes in the estuary.

Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., Democrats and Republicans are gathering behind closed doors to negotiate a new drought bill. A bill that passed the House last February was panned by Governor Brown and other state leaders as an unhelpful meddling in state water policy and a water giveaway to large agribusiness.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Have you seen the Fallen Leaf Lake study showing the 800 year drought from 1,200 years ago? University of Nevada Reno released that study 2 years ago and shows 60 to 80 foot trees still standing at the bottom of the lake. { Duration and severity of Medieval drought in the Lake Tahoe Basin }. That was long before the industrial revolution and shows this to be more of a cycle than what others would like to believe.

Irrespective of the 3 yr drought’s roots, Ric, the urgency and execution of sustainable-driven planning with equitable distribution for ALL, is here so using academics from an 800 yr drought won’t matter or help out, this is a new roadmap!