California Farms Use How Much Water? Nobody Really Knows

No comprehensive data exist on agricultural water consumption.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Information is the heart of California’s $US 2 trillion economy. A generation ago, the computational pioneers in Silicon Valley summoned ever-greater information processing power from a microchip and ushered in the Digital Age. The state’s research universities are among the world’s best at producing new scientific knowledge and invention. In nearly every sector, data — and the strategic decisions it enables — are a principal source of the Golden State’s economic triumph.

But in agriculture, the bedrock water-consuming industry in a state buffeted by a deep four-year drought, water data are not collected with anywhere near the same rigor and dedication. For such a technologically adept state, California knows surprisingly little about the water-using practices of the sector that it says withdraws nearly 80 percent of the water.

“The state produces estimates, but they are pretty coarse,” said Heather Cooley, water program director at the Pacific Institute, a research group. “We don’t really know how much agricultural water is used.”

–Heather Cooley, water program director

Pacific Institute

Arguably the most useful water data that California collects from farm regions is the result of SBx7-7, a 2009 state law that requires water districts supplying more than 4,047 irrigated hectares (10,000 acres) to measure the amount of water they deliver to farms, and to submit annual reports with monthly figures. Not complying renders a district ineligible for state grants. The law strengthens an earlier version by requiring more precise monitoring standards.

The information that districts report is farm-gate delivery data, which is the amount of water sent from a canal to an individual farm. These numbers primarily track surface water use, not groundwater, which is the other main source of irrigation water. There is no coordinated measurement of groundwater use in California.

“This is just the beginning,” Fethi Ben Jemaa, chief of the agricultural water use efficiency section of the Department of Water Resources, told Circle of Blue. “As we see more suppliers implement their measuring programs, we will get more accurate data.”

One of the goals of the 2009 law is to enable districts to charge farmers for water based on consumption. The idea is that farmers, if they pay for each unit instead of paying a flat fee, will use water more wisely. Ben Jemaa makes an analogy to urban water bills.

“When households know how much they use, they tend to use less and use it more efficiently,” he explained. Studies show that residential water use declines by 15 to 20 percent when moving from a flat fee to a volume-based charge, according to the Pacific Institute.

More Data Needed

As California confronts its worst drought in memory, the urgency of not wasting a drop is increasing. Researchers and officials say that better monitoring and reporting of water data, and easier access to the data that are collected is necessary for improving the efficiency and productivity of a scarce resource. Farmers are being pressed to duplicate the same water reporting requirements required of California’s urban centers.

Since June 2014, urban suppliers must submit monthly water use reports. The data formed the statistical baseline for the state’s first-ever mandatory water restrictions, which the Water Board approved earlier this month. In addition, AB 2572, a state law signed in 2004, requires all urban connections to be metered by 2025.

But for agriculture, neither reporting nor metering requirements are as strict. Farms and irrigation districts often have a better idea about water use than the state does. But some don’t measure use at all, and the information they do collect is not well cataloged. None of the researchers or state officials interviewed for this story knew of a database listing irrigation districts with groundwater metering requirements for agriculture. Enormous gaps exist, particularly for groundwater data.

“If you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” Ben Jemaa said.

State officials recognize the holes in their spreadsheets. The most recent update to the state water plan, published last October, highlighted an array of missing agricultural water data:

“Lack of data, mainly farm-gate irrigation water delivery data, has been an obstacle for assessing irrigation efficiencies and planning further improvement. The state lacks comprehensive statewide data on cropped areas under various irrigation methods, applied water, crop water use, irrigation efficiency, water savings, and the cost of irrigation improvements per unit of saved water. Collection, management, and dissemination of water use data to growers, water suppliers, and water resource planners are necessary for furthering water use efficiency.”

Missing Groundwater Data

California knows even less about groundwater than surface water. Between 1977 and 2010, farmers drilled 41,526 irrigation wells, according to the Department of Water Resources. State authorities do not know how much water is pumped from these wells each year. The state estimates groundwater use based on a formula: an estimate of how many acres of crops were planted, multiplied by an assumption about the average water needs for each acre of almonds or strawberries or tomatoes, minus the amount of surface water delivered.

Not only are farmers not required to report groundwater use. The state has no requirement that they measure how much they pump. Mary Scruggs, a geologist who works on the Department of Water Resources’ groundwater monitoring program, told Circle of Blue that the state does not know how many irrigation wells are metered.

“We don’t have that information,” Scruggs said. “We have no idea. It’s something we don’t track.” (The state did begin a partnership with local agencies in 2012 to track seasonal water level changes in key groundwater basins, a program known by its acronym CASGEM.)

Not all groundwater basins, however, are a mystery. Basins that have gone through a court process to sort out groundwater rights, most of which are in Southern California, do have metering and reporting requirements. Others levy fees on each unit of water removed from the aquifer. Orange County Water District, for example, charges a withdrawal fee, even though it does not set volume limits.

But three-quarters of California’s groundwater is withdrawn from the Central Valley, where groundwater monitoring and metering is less prevalent. That will soon change, however. A trio of laws signed last year requires tighter control over groundwater use. Local agencies will be in charge, but in order to manage the resources to the state’s satisfaction, they will need better data.

A Dashboard for the Farm

Better data is not only a matter of state oversight. Knowledge of pumping rates and water use can help farmers maximize water supplies, reduce waste, and cut energy consumption.

Like all mechanical equipment, irrigation systems wear down. Distribution lines clog, pipes break, pumps deteriorate. Instead of being applied evenly across a field, water in a poorly performing system might pool in certain areas. That wastes both the water and the electricity to pump it from the ground.

David Zoldoske, director of the Center for Irrigation Technology at Fresno State University, compares a water meter to information displayed on a car dashboard. A meter serves as an early-warning signal, like a flashing check-engine light, when a system’s performance begins to decline.

“Every system needs to be assessed and compared to its designed efficiency,” Zoldoske told Circle of Blue. “Nobody gets a pass. It’s more important than ever that growers make sure their systems are operating efficiently.”

Data in Action

Booth Ranches is an orange grower with headquarters on the eastside of Fresno County. Booth grows Cara Caras, navels, and Valencias on 3,360 hectares (8,300 acres) spread across the Central Valley.

Water use in the orchards is tracked in 20-acre blocks, said Dave Smith, the ranch’s general manager. A device called a tensiometer, placed near the tree roots, determines moisture levels in the soil. A drip irrigation system applies small amounts of water when a tree is thirsty.

Not all farms are so meticulous, the Pacific Institute’s Cooley said. Farmers that grow higher value crops such as fruits, vegetables, and nuts are more likely to measure water use than farmers who grow alfalfa or corn.

Booth’s system is akin to a soil X-ray. Managers can tell when the roots need moisture and deliver it accordingly. “If you water based on what you’re seeing on the surface, you don’t know what’s going on,” Smith told Circle of Blue.

“If there is water in the ground,” he added, “why add any more if you don’t need it? Once your glass is empty you know to put more water in it. If you overwater, you push the water below the root zone, and generally that water is lost to use.”

The system works. Smith said that Booth uses 2.1 acre-feet of water per acre on its orchards, roughly 20 percent less than the industry average.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

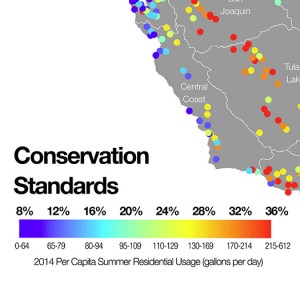

Infographic: California Urban Water Conservation Standards

Infographic: California Urban Water Conservation Standards

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!