California Groundwater Law Tests State’s Capacity to Oversee A Vital Resource

A year after passage, California begins building a new regulatory infrastructure

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

SOQUEL, California — On September 16, 2014, Governor Jerry Brown, cheerfully triumphant, signed into law the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which many observers assert is the most significant addition to California’s water protection code in a century.

Brown’s jubilance appeared justified in a dry, fast-growing, 165-year-old state that relies on prodigious volumes of freshwater from aquifers for its water supply, doesn’t really know how much water lies underground, and where leaders that sought changes to oversee the resource were subject to intense opposition.

Brown, himself, was one of the victims. During a drought in 1977, in his first term as governor, Brown appointed a commission to review the state’s water laws. The recommended protections for groundwater were not implemented. Lawmakers and the powerful agricultural sector did not feel the urgency to act.

“When the groundwater act was created, the watch phrase was ‘local control’…Now people are scratching their heads. They have to figure out how to form [an agency] and fund one.”

–Andrew Fisher, professor

University of California, Santa Cruz

The recent groundwater act is an attempt to change the course. The state’s drought emergency and record-low aquifer levels provided Brown with the political cushion necessary to push through the first statewide safeguards for aquifers, making California the last western state to adopt a regulatory system for groundwater.

But while Brown and other state leaders view the new law as a breakthrough in policy, it is not at all assured that building a new regulatory infrastructure to sustain California’s groundwater reserves will be a triumph of practice. The law’s requirements to establish local water oversight boards are complex and detailed. Moreover, the ultimate deadline for meeting the law’s major goal of much more cautiously consuming groundwater doesn’t need to be met until 2040, when California’s population is projected to reach 50 million residents, 11 million more than today. In almost every way, putting the groundwater law into effect is a 21st century test of a state’s capacity to respond to new and urgent ecological and economic conditions.

A year after the act’s passage, Californians have put aside lingering skepticism and are busy putting the text into action. Water managers, county supervisors, city and state officials, irrigation districts, and a bevy of other interested parties are scurrying to meet a cascade of deadlines that were laid out in the statute: deadlines for confirming the boundaries of their groundwater basins, for forming new agencies that will be tasked with overseeing water withdrawals from local aquifers, and for writing the management plans that will guide groundwater use for the next 25 years in the state’s major cities and farming centers.

To watch the process unfold is to witness the foundations of democracy. The same questions that Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison argued about and debated more than two centuries ago are now echoing in city council chambers and public forums from Clovis to Salinas. Who gets a seat at the table? Who gets to vote? How much is their vote worth? How will fees be collected? Who must pay for projects that reduce groundwater use or increase supply? How much will they pay?

With the law, California is, in effect, creating micro-states for groundwater, instituting new political divisions that are set, loosely, on basin boundaries, much as John Wesley Powell advocated, in 1890, for watersheds, as a way to govern the entire American West.

Crafting the fresh institutions that will oversee groundwater is contentious, tedious work, filled with late night meetings, mediators, technical details about geology and hydrology, and discussions about the nature of governance. The act — a two-step process that was designed to pull California groundwater regulation out of the hydrologic Dark Ages — forces agencies that may never have collaborated to agree to a long-term vision for water supply and availability.

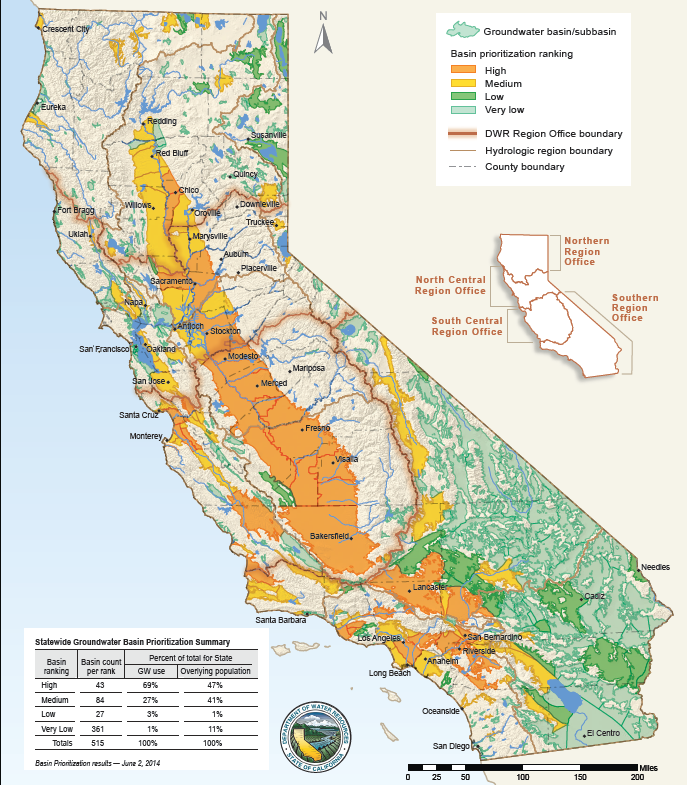

First, the 127 groundwater basins that are covered by the law must form a Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) that will have the power to measure and monitor groundwater use, levy fees on users, set standards for new wells, and enforce compliance with the law. The deadline to form an agency is June 30, 2017.

Second, the GSAs, once formed, must write sustainability plans that will balance water withdrawals with inflows by 2040. The plans are due in 2020 or 2022, depending on the severity of groundwater depletion in a basin. The state will evaluate the plans to ensure that they meet minimum criteria, but the local agencies, as they lobbied for, are in the captain’s seat.

“When the groundwater act was created, the watch phrase was ‘local control’,” Andrew Fisher, a University of California, Santa Cruz, scientist who studies groundwater, told Circle of Blue. “The legislation was vague on the details. It said nothing about what a groundwater agency looks like. Now people are scratching their heads. They have to figure out how to form one and how to fund one. It’s not quite clear how to do that. It’s going to be an interesting 20 years.”

Agency Formation Depends on Local Relationships

Forming a GSA is straightforward in some areas. The legislation authorizes 15 existing water agencies to become the GSA in their jurisdiction. They are all special districts that were previously established by the Legislature to manage groundwater.

“We’ve been given a pass card,” Mary Bannister, general manager of Pajaro Valley Water Management Agency, told Circle of Blue. By that, Bannister means that Pajaro Valley, one of the districts named in the act, is ahead of the game. Its boundaries, function, and purpose have already been legally defined and they were confirmed during an August board meeting. The agency can move to step two: writing a sustainability plan.

The rest of the state is still on step one: forming a GSA. In most cases, the agencies that will regulate groundwater use are being created from scratch, stitched together from the fabric of existing institutions.

A few paces in front of the pack is the Soquel-Aptos Groundwater Basin, a small basin in Santa Cruz County, on the coast. Soquel Creek Water District, one of a number of water providers in the basin, declared a groundwater emergency in June 2014. Groundwater is the district’s only water source, more water is pumped from the aquifer each year than is recharged by rainfall, and the Pacific Ocean is slowly creeping inland, which is a threat to coastal wells. The basin is one of 21 “critical” basins in the state, as designated by the Department of Water Resources.

At an August 20 meeting, a basin coordination committee that was formed in 1995 added new members, in order to implement the groundwater act. Santa Cruz County, the city of Santa Cruz, and three members representing private well owners joined Soquel Creek and Central Water District. The 11-member committee will most likely become the GSA for the basin.

“The spirit of cooperation among the entities is really good,” Tom LaHue, a Soquel Creek board member, said at the three-hour meeting, which ended a few minutes before 10 p.m.

A number of questions are unresolved. Soquel-Aptos might appeal to the state to revise its basin boundaries (see sidebar). The committee must decide whether to pursue water supply projects jointly or as individual agencies. The biggest point of contention at the meeting was the speed of the GSA formation.

“It’s three steps forward, two steps back on GSA issues,” Melanie Mow Schumacher, special projects manager for Soquel Creek Water District, told Circle of Blue. “The discussions about assessing fees — those are the steps back. Recognizing the fact that we need to be doing something about groundwater, that is running forward.”

Observers in other basins also see money as the most significant hurdle for the GSAs.

“The biggest vulnerability for SGMA is how to get funded,” Bannister said.

Bannister speaks from experience. After Pajaro Valley was established by the Legislature in 1985, she said it took 15 years for the fledgling agency to begin developing projects that addressed the basin’s declining groundwater levels.

“It took the metering of wells, five years of hydrologic modeling, and $US 5 million to $US 10 million in expenses to get us to the point where we could identify solutions. The question for the new agencies is how do you pay for it?”

The state will provide some assistance. Local agencies can apply for $US 100 million in planning grants, part of the $US 7.5 billion water bond that voters passed last November.

Go Quicker

The most frequent criticism of the SGMA process is that it is too slow. Sustainability plans are due by January 31, 2020, for the critical basins and January 31, 2022, for the other 106 basins covered by the law. Though the state will evaluate progress toward the plan goals every five years, basins do not have to be in balance until 2040.

“I worry that by the time we get our act together and implement the plans we’re going to be facing a more immediate crisis of groundwater supply,” Kevin Haroff, an attorney at the San Francisco office of Marten Law, told Circle of Blue.

Even Governor Brown says that legislation is going too slow, claiming in an August 23 interview on NBC’s Meet the Press that “we’re not aggressive enough” but that the state “will be stepping it up year by year.”

The critics worry because the state leaned so strongly on groundwater to survive the four years of drought that the crutch might snap if dry times continue much longer. Residential wells in the Central Valley are going dry at an unprecedented rate. The land, with the water removed, is sinking in certain areas at record pace. Saltwater, held in abeyance along the coast thanks to a multitude of recycling projects, is likely to creep inland as more groundwater is pumped.

But those implementing the act’s provisions — the irrigation districts, county officials, water managers, and well owners — have a different view. They say the timeline feels fast, or “incredibly aggressive,” as Bannister said.

When asked about the speed of implementation, Rob Johnson, deputy general manager of the Monterey County Water Resources Agency, paused before answering.

“It’s a very interesting question,” he told Circle of Blue. “For the people to put an agency in place and write plans and change their practices, it will take that amount of time.”

Monterey County is part of the Salinas River Basin, which is another of the critical basins that must submit a plan by 2020. Unlike Soquel-Aptos, however, there is little agreement about the form a GSA should take.

Initially, the Monterey County Water Resources Agency said that it alone would be the GSA. Farmers and the city of Salinas objected to that concentration of authority.

“We said, ‘No, that’s not going to work for us,’” Gary Peterson, director of public works for Salinas, told Circle of Blue. “That would be abdicating land use to the county. We needed more equitable management.”

Farm interests, on the other hand, feel that they should have the controlling stake in the GSA, since agriculture uses between 85 and 90 percent of the basin’s groundwater.

“We feel that voice is commiserate with our use of groundwater,” Norm Groot, executive director of the Monterey County Farm Bureau, told Circle of Blue.

To help guide the basin to a resolution, a coalition of competing interests — the Monterey County Water Resources Authority, Monterey County, the city of Salinas, the Monterey County Farm Bureau, the Grower-Shipper Association, and the Salinas Valley Water Coalition — elected to bring in a facilitator.

Plans Will Wait

The GSAs are only a beginning, an intermediate step toward sustainable groundwater use. The harder questions come after the GSA is established, when the rules of the game will be written. Will basins focus on reducing demand or increasing supply? Who will pay for those projects? How will landowners in parts of a basin that are not experiencing detrimental declines in groundwater feel about paying for projects that benefit people living in areas that do have problems?

Groot, for instance, said that the farm interests in Monterey County do not want a reduction in groundwater pumping, that they prefer measures that increase supply, such as pulling out vegetation in the Salinas River channel.

Even those basins with widespread agreement about the shape and composition of a GSA face a steep path when they write their sustainability plans.

Schumacher, of Soquel Creek, said that the idea for the Soquel-Aptos basin is to stage the discussion in two parts. First, move forward with the GSA, which everyone agrees is a necessary step. Filing for the GSA sooner will allow for a head start on the details of the sustainability plan, which is due in five years.

As for consensus on what goes into the plan, “we’re just not there yet,” Schumacher said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Keystone cops.