Concerns over Bottled Water and NAFTA Swirl during British Columbia Drought

Citizen petition calls for higher fees on Nestle and other bottled water companies while authorities worry about trade agreement implications.

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

When water supplies tighten, scrutiny of all uses, especially those deemed inessential, intensifies. It is happening in California, and it is happening in dry British Columbia where, after a surge of interest in an online petition that called for higher commercial water charges, government officials announced this week that they will review the fees that bottled water companies pay to extract groundwater.

Some officials worry, however, that if the government increases the price of raw water so that revenues rise above the cost of administering the province’s water management program — in other words, if it profits from the resource — the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) investment provisions will kick in, and the government will lose control over its aquifers, lakes, and rivers to American businesses with an eye on Canadian water.

Experts in international trade law say that scenario is far too simplistic and does not reflect current interpretations of the trade agreement.

“The fact that Nestle is allowed to take groundwater and bottle it does not mean that all groundwater or lake water is commodified,” explained Howard Mann, an Ottawa-based lawyer who focuses on investment treaties and international law.

Though never tested in court, countries are allowed to restrict commercial access to water in the name of environmental protection, Mann told Circle of Blue.

“Governments can set quantitative limits on extraction for environmental purposes under trade law,” he said.

Drought Focuses Attention on Water

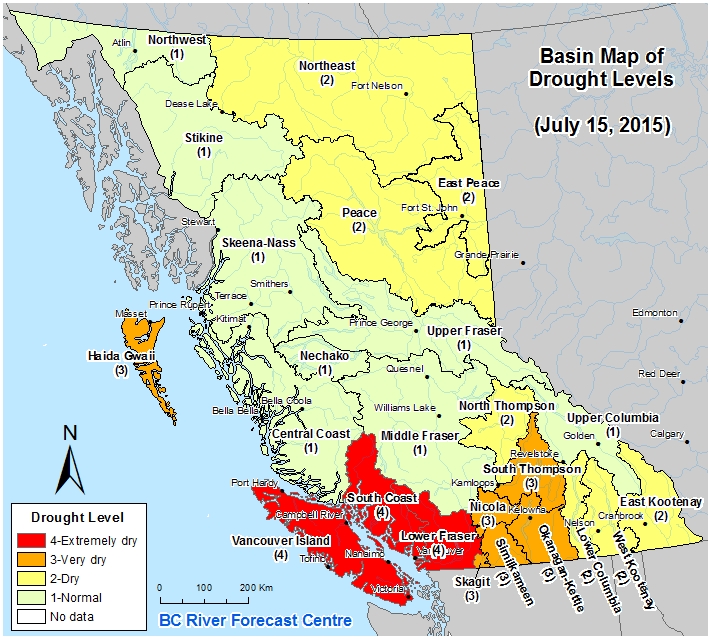

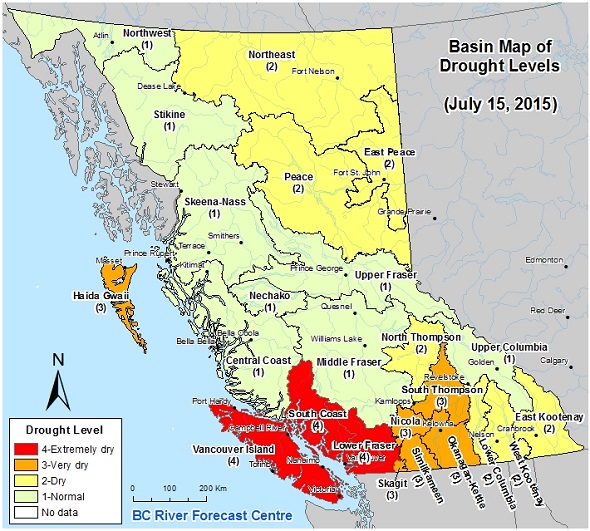

British Columbia, a land of mountains, glaciers, and coastal rainforests, is enduring its driest summer in decades. Several rivers are flowing at record low rates and drinking water reservoirs in metro Vancouver are below normal. On July 15, the provincial government, for the first time since a ratings system was put in place in 2010, downgraded two hydrologic regions in the southwest corner of the province to the most severe drought rating.

As in California, which is in the midst of its hottest and driest period on record, the British Columbia drought has focused new attention on the bottled water industry. A petition posted in February to the website SumofUs.org asks provincial authorities to increase the fees charged to bottled water companies, “to make sure Nestle can’t walk away with our water without paying a fair price.” The petition has garnered more than 225,000 signatures.

On July 13, Premier Christy Clark acknowledged the growing public pressure and announced that the fees would be reviewed.

“We are going to go back and look at the pricing for the big water bottlers in the province and make sure that’s appropriate, because what we’ve heard is people say they don’t think it’s appropriate, they think that we should be at the top end, charging a little more for some of that water that the big bottlers are extracting,” Clark said, according to radio station CKNW.

The charges for water bottlers and other commercial and institutional consumers increased as part of the Water Sustainability Act that passed the provincial Parliament in February. Beginning next year, bottled water companies will pay $CN 2.25 per million liters ($US 1.73 per 264,000 gallons) — the same rate as amusement parks, churches, garbage dumps, and shipyards, and more than double the rate for golf course irrigation and greenhouses. The current rate for water bottlers is $CN 0.85 per million liters ($US 0.65 per 264,000 gallons).

The premier’s press office did not respond to Circle of Blue’s question about whether all water fees will be reviewed, or only fees charged to water bottlers.

NAFTA Concerns

The furor around the fees has prompted questions about the influence of NAFTA, the free trade agreement signed in 1994 by Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Recognizing that water would be a volatile issue, the three countries stated in 1993 that water in its “natural state” would not be subjected to the terms of the trade agreement.

Mann said that trade law provides exceptions for environmental protection. Governments can set limits on water extraction, Mann said, as long as they apply equally to domestic and international companies. Canada did as much in 1999 when Parliament instituted a moratorium on bulk water exports after Sun Belt Water, an American company, attempted to ship water from British Columbia to California in the 1990s.

Governments can even strengthen the rules if more protection is necessary, Mann said.

“It is still possible to tighten up regulations in the future as long as they did it for everyone at the same time,” Mann explained.

Mann could recall no trade law decisions regarding restrictions on water extraction. Neither could Paul Kibel, a professor at Golden Gate University School of Law in San Francisco who teaches environmental law and has written about NAFTA court cases. A few cases have run around the margins, but none has clearly addressed the issue. Sun Belt Water filed a notice of intent to sue under NAFTA’s Chapter 11, the section that prohibits discrimination of foreign investor and taking of property. Sun Belt claimed that preferential treatment was given to a Canadian company that was also interested in exporting water, but Sun Belt did not proceed with the claim. Then in 2004, a group of farmers in Texas brought suit against Mexico for allegedly withholding water from reservoirs in the Rio Grande Basin that was supposed to flow to Texas. The tribunal ruled on a technicality and did not address the merits of the case, Kibel said.

Kibel told Circle of Blue that the lack of precedent makes it difficult to gauge how a tribunal would rule if a water case was brought forward.

Governments concerned about NAFTA ought to look closer to home first and shore up their own legal codes for water use, Mann said.

“The biggest problem,” he concluded, “is that governments generally don’t have a holistic regulatory regime in place to start with.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Just wanted to say what a nice piece the BC/NAFTA piece is. The entire world of water pricing and discrimination in favor of the home team is going to get more interesting and this piece highlights an important and underplayed part.

In addition to Mr. Mann’s comments, we all need to be aware and make sure governments and other foreign or domestic interests understand that the Crown and provinces in Canada and U.S. States hold water as a commons, that is sovereigns for citizens, and absent express authorization to license or commodify, it cannot be exacted by private interests. Moreover, any removal of water that would violate the public right to navigation and fishing in Canada or the public trust in water in the states is not only prohibited, by definition not authorized, nor could it be authorized.