Gila River Diversion in New Mexico Pits New West vs Old

Debate demonstrates the power of water in the drying American West.

Cottonwood trees flank the Gila River in southwest New Mexico. In November, a state agency voted to move forward with plans to divert more water from the river. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

GILA, New Mexico—Woven in braided channels as it cascades through the Mogollon Mountains, the Gila River flows quick and clear on a spring morning between a corridor of cottonwood trees so green they appear radioactive.

That’s not nearly the case 400 kilometers (250 miles) downstream in Pinal County, Arizona. Impressed there on the roasted desert scrubland is the memory of a river.

Like a trail from yesterday, the course of the dry Gila still cuts across the central Arizona landscape. The mattress of sand in the dusty bed yields so readily that a traveler attempting a traverse sinks to the ankles. Though occasional monsoon floods fill its banks and subsurface moisture nourishes pockets of hardy thistle and long-stem grasses, the Gila River southeast of Phoenix is a dead river.

The contrast in conditions between the downriver and upriver stretches of the Gila highlight a notable regional struggle over the Gila’s flow. Upstream communities in New Mexico want more of the Gila’s water and a 2004 Congressional statute gives them some potent legal authority to seize it — maybe.

The proposal to divert the Gila River has attracted considerable opposition, invited intense scientific scrutiny, could involve large public investments, and is being aggressively pursued by the New Mexico agency charged with studying the diversion idea.

In short, the currents of the Gila and its tributaries are a revealing tale of the arduous decisions about access to water facing desert communities in the steadily drying American West. The effort to divert the river’s water pits pioneer beliefs that water left in a river is a wasted resource against 21st century ideas of conservation, efficiency, and environmental protection.

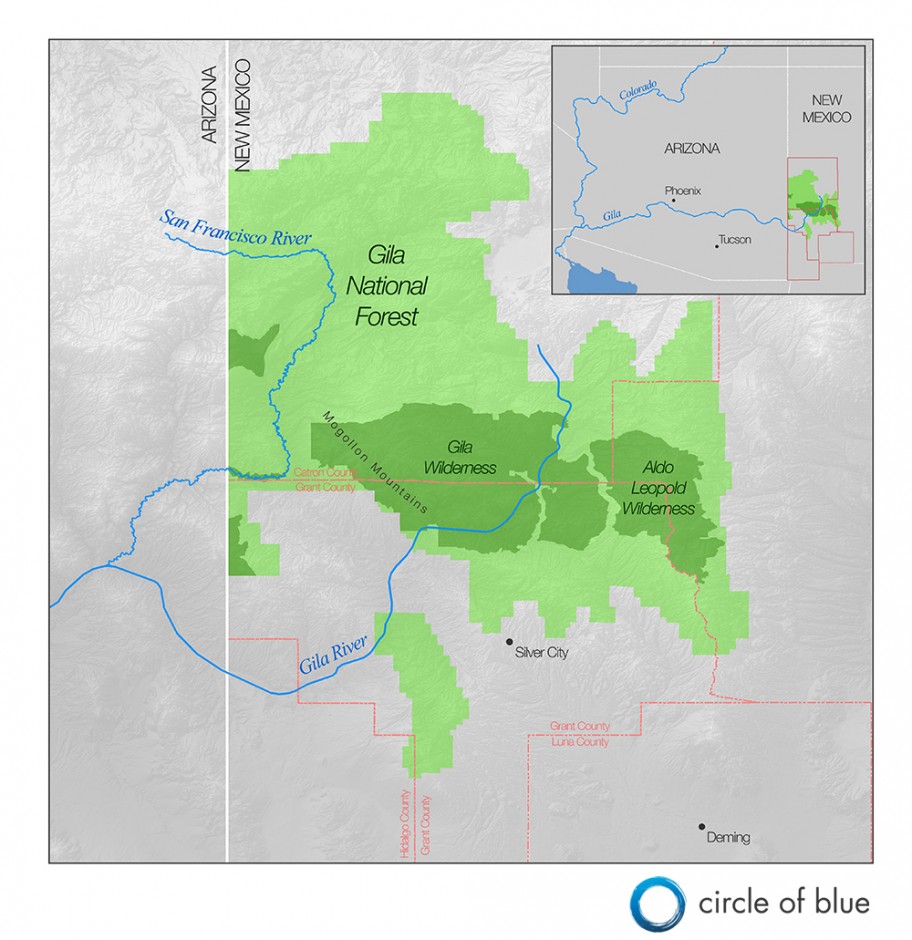

Grant County and American Wilderness

Nearly a century ago this corner of southwest New Mexico was where Aldo Leopold, the great American naturalist and then a young ranger for the U.S. Forest Service in New Mexico, gave substance to the idea of permanently protecting great expanses of American wildlands. In 1924, prodded by a three-page proposal from Leopold, the U.S. Forest Service designated 755,000 acres of the Gila National Forest as the nation’s first wilderness area.

Sunrise over the Mogollon Mountains, southwestern gateway to the Gila Wilderness, the nation’s first federally designated wilderness area. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

That action, in response to the spread of roads in national forests, sought to balance solitude, development, and the preservation of forest assets, including the waters of the Gila River. Today, the sparsely populated region is again debating how to effectively join competing choices about water use, public investment, and the wise use of natural resources.

Like so many communities in the West, southwest New Mexico’s top priority is securing its freshwater resources. Right behind on the list of goals here is the best way to build an economy and society in the desert. The opportunity to achieve these goals has both presented itself in a novel way, and also attracted considerable dismay about costs, complexity, and wisdom of actually sharing water with new tools and practices.

Eleven years ago Congress approved legislation that allows four counties in southwest New Mexico to take more water from a river. The Arizona Water Settlements Act, approved in 2004, allows the counties to withdraw up to 14,000 acre-feet per year from the Gila River and the San Francisco River, its tributary, to be used for irrigation, towns, industrial growth, or other purposes. That is roughly 5 percent of the region’s current water withdrawals from rivers and aquifers. Eighty-five percent of current withdrawals are directed to agriculture.

Supporters of the legislation were elated. They said that drawing more water from the Gila and the San Francisco will help reduce reliance on the region’s groundwater reserves, a supply that supporters said cannot be sustained in the long run.

Lining up against the idea of diverting water from the two rivers are environmental groups and budget hawks who are backed by numerous technical evaluations that find that the obstacles are real and formidable. Among those impediments are:

- The Gila doesn’t have enough water on most days of the year to meet the legal thresholds for diverting the river’s water, and flows are expected to steadily decrease as the climate warms.

- Based on the historic record, less than 12,000 acre-feet of water on average is actually available when accounting for the legal constraints on the timing of diversions, according an analysis led by the Nature Conservancy.

- In order to supply water for diversions, at least one dam, and perhaps several more, would need to built in side canyons for reservoirs with bottoms composed of porous soil. The estimated cost: between $US 83 million and $US 598 million depending on the dam, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

- Evaporation rates are high in the region, and the evaporation counts against New Mexico’s share of the water.

- To supply Deming, the region’s largest town, five pumping stations would lift the water 1,680 feet over the Continental Divide. The electric bill to operate the pumps is expected to reach nearly $US 3 million annually.

- Six endangered species live in the river ecosystem and the requirements of the federal Endangered Species Act could derail development.

- Opponents of the project contend that a mix of conservation, wastewater recycling, and wise use of groundwater is a cheaper, less destructive way to meet the region’s needs.

The Bureau of Reclamation, the federal government’s chief dam-building agency, found that costs significantly exceed benefits for all 11 of the diversion and reservoir options that it analyzed. These factors and more have led many in the state to question the wisdom of a project whose cost to build and operate, which depends on the option selected, could range from $US 62 million up to $US 775 million.

“The major problem is that the project is not feasible,” Norm Gaume, one of the strongest critics, told Circle of Blue. Gaume is a former director of the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission, the state agency that is evaluating the diversion.

“There’s not much water there,” Gaume added. “The project is extremely exposed to climate change impacts. The cost is just over the top, and the environmental impacts are extreme. It’s an egregious proposal.”

Nonetheless, the ISC voted last November to continue pursuing the project.

“It would be irresponsible for the ISC to ignore the annual average of 14,000 acre-feet of additional water available to New Mexico in the 2004 Arizona Water Settlements Act,” wrote spokeswoman Lela Hunt in a statement to Circle of Blue. ISC commissioners declined a request for an interview.

The Proponent

The office of Anthony Gutierrez is bright white and appropriately cluttered for the planning director of Grant County. Gutierrez is also the chairman of the Gila-San Francisco Water Commission, a forum for regional water decisions. He spoke with Circle of Blue in March, four months after the ISC’s November vote.

“We want to keep New Mexico’s water in New Mexico as best we can,” Gutierrez said. “I hate to think of water as a commodity but our social well-being has made it that. It’s more valuable than gold or oil to us.”

Anthony Gutierrez, chairman of the Gila-San Francisco Water Commission, says that the region should use the Gila River water granted by Congress. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

What the nine ISC commissioners approved last fall was a formal declaration of their intent to divert water from the Gila. The declaration was required under the Arizona Water Settlements Act (AWSA) by the end of 2014. By making the declaration, the state has a year to form a governing body for the diversion, officially called the New Mexico Unit of the Central Arizona Project, the federal canal that moves the Colorado River through the heart of Arizona. The Gila-San Francisco commission wants to be in charge of the New Mexico Unit, meaning it will be responsible for financing and operating a large project for a four-county region that is home to just 62,000 people.

The AWSA is a tangled piece of legislation. Its primary purpose was to settle Native American water rights in Arizona. To garner support from the New Mexico delegation, water from the Gila was added to the package and federal dollars sweetened the deal. The act provided New Mexico with $US 66 million to spend on any water supply project in the four-county area. Because it was pegged to inflation, the amount available has grown to $US 90 million. An additional tranche of money, up to $US 62 million, is earmarked for the capital cost of building a diversion.

An agreement ratified as part of the AWSA, called the Consumptive Use and Forbearance Agreement, sets hydrological limits on when water can be removed from the river. Because the Gila’s flow has sharp peaks and deep valleys, in some years no water would have been diverted, according to the Nature Conservancy study. By mid-century, average river discharge is expected to decrease by 6 percent, based on five climate models.

That study also concluded that a diversion would harm the floodplain by reducing groundwater recharge and increasing land erosion during the Gila’s occasional fierce floods. Drawing more water from the river, especially during the spring snowmelt, will cut off fish habitat and reduce spawning grounds for two endangered species, the loach minnow and spikedace.

Gutierrez is sympathetic to claims of environmental damage, but he says they should not be a deterrent.

“I live on the river,” Gutierrez said, referring to his home in the Gila Valley. “I spent my childhood on the river. I want to preserve the resource. But the conservationists carry their goals too far. Plus, I’m a planner. I can see that we already have water issues. Drought is affecting the water supply.”

The AWSA, he asserted, is a tantalizing proposition: “Here we have a congressional act to keep water in New Mexico. I don’t see why we wouldn’t. It might be our last opportunity.”

Gutierrez says this often: I’m a planner. His background is engineering and infrastructure development. All money spent by Grant County for capital projects — roads, buildings, water supply — comes through his office.

Explaining Desire for Diversion

In a 90-minute conservation it is clear that the commission’s plan for the Gila diversion, at this point, is more a desire for water than a coherent blueprint. Mainly this is because no single project from the dozens of combinations of diversion points and reservoir locations has emerged as a winner. A final cost will not be known until environmental reviews are completed by 2019.The commission is basing its estimates on a $US 350 million project, Gutierrez said.

But Gutierrez does not believe that the unit cost for water — what a city or a farmer will pay for an acre-foot — is required information. He believes that contracts for the water before construction begins are unnecessary as well. “There’s already a need,” he said. “Once the water is available people will use it.”

Is this Field of Dreams assumption — that if the project is built, someone will pay for the water — sufficient for the commission to continue pushing for construction?

“That assumption is enough for me,” replied Gutierrez, who talks about investing the AWSA money and using the returns to help finance the project. “It may not be enough for the environmental community.”

Conservation Alternatives for AWSA Funds

The assumption that paying customers will eventually come knocking is not enough for Gaume and countless other critics of the Gila diversion. According to Gaume’s calculations using Bureau of Reclamation data, the monthly cost of water for residents of Deming would rise more than 10-fold if they paid for their full share of the project.

Allyson Siwik, executive director of the Gila Conservation Coalition, which opposes the diversion, said the group has been making the economic argument from the start.

“People do not want to face facts that the New Mexico Unit is a pipe dream,” Siwik told Circle of Blue. “It defies logic when we could fund non-diversion alternatives to meet our needs at a fraction of the cost.”

Dozens of proposals were submitted to the ISC from towns, irrigation districts, and watershed organizations for spending the AWSA money. The ISC selected 15 projects to consider for funding, 12 of which do not divert water from the Gila. Those projects include lining irrigation ditches to cut seepage losses, municipal conservation programs, new groundwater wells, and recycling wastewater. Siwik points out that all 12 could be funded in full by the AWSA money. The combined cost of the 12 projects, according to the ISC, is $US 72 million. The ISC, however, decided at recent meetings to allocate $US 9.1 to the non-diversion projects.

A few of the non-diversion projects are better bargains. The Bureau of Reclamation found that municipal conservation and wastewater reuse had the highest ratio of benefits to cost.

Wait and See

Resembling a band of snapped elastic, Turkey Creek Road on the eastside of the Gila River is a warped and looping path of dirt and gravel wide enough at its narrowest for a single car. The eight-mile drive to road’s end takes 45 minutes.

This bend in the Gila, just downstream from the wilderness boundary, is one diversion site analyzed by the Bureau of Reclamation. Photo © Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

In the hour after sunrise only one soul, a camper, is in the area, part of Gila National Forest. Here, just downstream from the Gila River’s junction with Turkey Creek, is one of the diversion points evaluated by the Bureau of Reclamation. Less than two miles upstream is the boundary of the Gila Wilderness.

What the site will look like in 20 years is unknown. If this diversion point is selected, the road will be widened to smooth the passage of excavators, concrete mixers, and dump trucks. The heavy machinery would carve out an 8.5-meter (28-foot) wide canal parallel to the river. The water would travel 51 kilometers (32 miles) to a reservoir plugging Spar Canyon, east of the river in the Gila Valley.

Gaume thinks that such a scenario is unlikely. “The project will die under its own weight,” he said. “I don’t see how another outcome occurs.”

What is certain are the meetings. Over the next months the Gila-San Francisco Water Commission must persuade local governments to back its bid to lead the New Mexico Unit. That agreement must be approved by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior and completed by November 26. Then the lengthy federal environmental review process can begin.

Even if the Gila diversion ultimately fails, the idea will not die. If history is a guide, as long as there is water in the river, someone will want to take it.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!