In Oakland, Still A City With Thorns, A New Garden Emerges (Part II)

Quality of life and economy thrive with greater care for water, energy, air, and waste.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

The event that touched off Oakland’s reappraisal of itself and its fortunes was a natural calamity. On October 17, 1989, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake crumpled the Bay Area. In Oakland, 42 people died when a 1,200-meter (3,900-foot) elevated section of Interstate 880 in West Oakland, the Cypress Freeway, collapsed. Across the city’s central core, signature buildings, including City Hall, were heavily damaged.

A wildfire in October 1991, in the wealthy neighborhoods on the hills east of downtown, destroyed over 3,000 residences and killed 25 people. As it so often does in California, nature made it plain to Oakland residents that no block – rich or poor – was immune to calamity.

The two disasters, and the decisions about recovery and reconstruction, started a deeper civic discourse about Oakland’s well-being and the use of public spending to improve it. In a remarkable series of policy steps, a generation-long study in policy and program push-and-pull between the city and the state, Oakland went to work on itself.

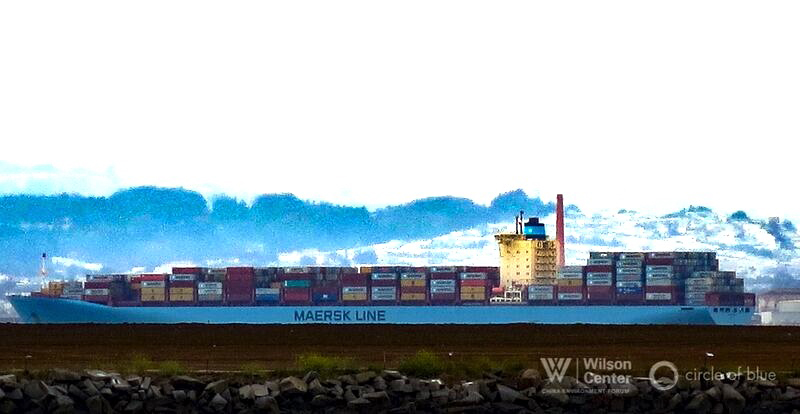

West Oakland, one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, set between downtown and the Port of Oakland, emerged as an early center of activity. The neighborhood of 20,000 residents, most of them African Americans, became active in the national environmental justice movement to focus attention on communities of color affected by high levels of pollution.

West Oakland activists expressed resolve to clear the air of soot and chemical pollutants first by rerouting the Cypress Freeway after its collapse, and second by limiting diesel air pollutants from trucks and ships at the neighboring Port of Oakland, the nation’s fifth largest container port, where half of the trading volume and value is with China.

The neighborhood campaigns gained significant technical and research assistance from the Oakland-based Pacific Institute, which is affiliated with Circle of Blue. In 2000, the well-regarded science and resource group helped to form the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project to take careful measurements of the levels of pollutants and provide help in communicating the results.

As researchers involved in the indicators project brought forward evidence of the relationship between high levels of asthma in West Oakland children and soaring concentrations of soot and pollutants in the air, public pressure steadily built on highway authorities and the seaport.

–Scott Wentworth, energy engineer

City of Oakland

As part of our Global Choke Point project the China Environment Forum, a program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and Circle of Blue are closely studying trends in energy and water supply and use in two Pacific port cities – Oakland and Shenzhen, China. The Choke Point: Cities project builds on five years of multimedia reporting and convening that examined the water-energy-food confrontations in China, Australia, the United States, India, Mongolia, and the Arabian Gulf.

Among United States port cities, few have met the challenge of responding to warmer, drier, more resource-scarce conditions as has Oakland.

Clearer Air

It took a while, but the Cypress Freeway was reconstructed further inland. In 2006, in large measure due to the activism in Oakland, the state approved new regulations to cut air pollution from state seaports. Three years later Oakland port directors announced the start of a $US 650 million program to cut soot and dust from diesel emissions by 85 percent by 2020.

The first step in the plan was to install strict emissions limits on trucks calling on the port. Under a $US 32 million state grant, truck owners were provided financial assistance to add filters and other pollution control equipment to their engines. Oakland also spent $US 60 million to install electric power hookups at port berths. No longer are ships that regularly visit the port allowed to operate with their diesel engines running while loading and unloading.

According to the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, installation of the shore power equipment cuts 11 tons of air pollutants and particulates annually at each of the 11 berths equipped for electricity. In 2014, researchers from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory announced they had measured what they called “dramatic reductions” in diesel emissions at the seaport. The median emission rate from diesel trucks operating at the port declined 76 percent for black carbon, a major portion of diesel particulate matter and a pollutant linked to global warming.

Dr. Thomas Kirchstetter, an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, said that between 2009 and 2013 the average emission rate for nitrogen oxide, which leads to the creation of ozone and particulate matter, fell 53 percent.

“There’s no plug and play with this kind of work,” said Richard Sinkhoff, the port’s director of Environmental Programs and Planning. “It’s a design process. How do you take regulatory requirements and design a program to deliver the project’s goals? In this case it’s working.”

It is working well enough, in fact, that West Oakland’s cleaner air is a factor in encouraging new home buyers in the neighborhood that features block after block of early 20th-century single family houses. Now concerns about change and gentrification have replaced pollution at the top of the list of neighborhood priorities.

Cleaner Water

The story of how West Oakland achieved cleaner air is consistent with so many other environmental goals that Oakland set and is meeting.

The Oakland government has elevated stormwater management, for instance, to a high public priority to stem water pollution. The Oakland seaport, which operates on more than 240 hectares (600 acres) and manages 30 kilometers (19 miles) of bay shoreline, approved an ordinance and started a program earlier this year to hold and treat stormwater draining off its land. By slowing the flow and directing it to storage basins and filtering equipment, the port will be able to keep trash and other contaminants from entering storm drains and San Francisco Bay.

The port can look to other city agencies for expertise. Oakland developed and manages one of the country’s best programs for restoring creeks and using natural buffers and swales to cleanse stormwater. Much of the work is financed by a $US 198 million bond fund, approved by city voters in 2001. Half of the money is directed to reconnecting Lake Merritt to the tidal influences of San Francisco Bay, building pedestrian bridges, redesigning roads to slow traffic, and expanding the park’s bike lanes and green spaces.

Lake Merritt’s restoration is polishing up the nearby neighborhoods, which have become choice places to live and open businesses.

“When I first started working in Oakland in 1984, we jogged around the lake on broken sidewalks, and sometimes the water was stagnant and stunk,” said Gary Wolff, the director of StopWaste, an Alameda County-wide agency charged with overseeing recycling and green building programs. “It’s phenomenal now. My daughter lives in the up and coming east side of the lake and close to all that restored property. It’s beautiful.”

In energy efficiency, pollution control, and waste management, Oakland also is setting national standards of policy design and performance. Three programs form the foundation of the city’s work:

- A 2006 plan, put into motion by then-mayor Jerry Brown, to cut Oakland’s production of solid waste – from homes, businesses, construction, and organic materials—to zero by 2020.

- A 2012 Energy and Climate Action Plan, among the country’s most ambitious, to cut carbon emissions 36 percent by 2020.

- A 2010 green building code and standards to require new home, office, retail, and recreation buildings to be much more energy efficient.

Energy Efficiency and Climate Change

Oakland, it turns out, was among the first cities in California to design and enforce energy efficiency standards for new homes and buildings. In 2009, pressed by West Oakland’s Ella Baker Center and Van Jones, its charismatic Yale-educated founder and director, the city started to develop its Energy and Climate Action Plan, which was consistent with the 2006 state climate emissions reduction statute. Governor Jerry Brown has since signed an executive order that puts California on the path to reduce carbon emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

–Gary Wolff, director

StopWaste

With city and state carbon reduction limits in place, Oakland set out to meet them. The city audited its buildings, analyzed its fleet of vehicles, and reviewed its solid waste infrastructure with the clear goal of being more efficient. A big downtown parking garage, for instance, was rewired, relit with low-energy lighting and controls, and outfitted with electric vehicle recharging stations. The retrofit, according to city figures, saves $US 55,000 in annual operating costs and 343,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity, equivalent to 111,000 kilograms (246,000 pounds) of CO2 emissions annually.

“We’ve taken the same approach with all of our infrastructure,” said Scott Wentworth, Oakland’s engineer. “The city has 2 million square feet of space in 116 buildings. We have 1,500 meters, 600 intersections, 35,000 streetlights. We’re changing lights, putting in new equipment, and doing what we need to do to meet the city’s climate reduction goal.”

With the help of StopWaste, Oakland, in 2000, was one of the first cities in the country to adopt an ordinance requiring that 50 percent of construction and demolition waste be recycled. In 2005, Oakland was among the first cities in the country to adopt a green building ordinance for municipal projects. In 2006 the city encouraged new homes and offices to be green by creating incentives for green developers and in 2010 strengthened the program by requiring energy-efficient certification for large commercial projects, and for single and multi-family homes.

Oakland was among the first cities in the country to adopt a green building ordinance for new homes and offices, and in 2010 strengthened the program by offering technical assistance to builders. A good bit of the city’s green building codes and programs were embraced in CalGreen, the state green building code.

In the waste management arena, Oakland is similarly focused on reducing the generation of energy-wasting trash and recycling, both of which translate into carbon emission reductions.

Oakland’s big wastewater treatment plant recycles food and organic waste in huge digesters that produce methane gas that is burned to produce 11 megawatts of electrical generating capacity, which is more than the plant consumes to operate equipment. The plant, owned and operated by EBMUD, the water utility, is a central fixture in Oakland’s aggressive Zero Waste recycling program to drastically reduce the amount of home, business, and construction waste destined for landfills.

Recycling Everything Not Tied Down

Three years ago the city and Alameda County banned conventional recyclable wastes from businesses – plastic, glass, paper, metal – from being shipped to landfills. This year, Oakland signed a contract with Waste Management, its designated waste hauler, that also blocks commercial organic wastes from being landfilled.

StopWaste makes a strong case that such forward-thinking waste reduction measures translate into big reductions in CO2 emissions. Every ton of corrugated cardboard that is recycled reduces carbon emissions by 3.6 metric tons (four tons), says the agency. Recycling a ton of plastic saves about two tons of CO2 annually. The new requirements for green waste and recycling will save an average of 450,000 metric tons (496,000 tons) of CO2 annually in Oakland, according to city projections.

“Those of us who see all the work that still needs to be done may not realize how well we are doing,” said Wolff. “People are still being killed by random gunfire, and not just in low-income neighborhoods. Street litter is common, even though recycling is up. Progress, poverty, death, and start-ups. We’ve got it all. Oakland is a city being transformed. I understand that completely. ”

In many ways caring for a city is like the parenting of a child. It takes most of a generation of careful nurturing for the results to become apparent. Oakland’s growing tech sector, its rising property values, and its restored parks crowded with visitors are evidence of the city’s vitality.

In the guts and bones that support the city there is much more to do, though, to reach Oakland’s goal of 36 percent carbon reductions by 2020, or achieving zero waste production, or making all of its neighborhoods safe.

Heavy truck and passenger vehicle traffic through the city accounts for 40 percent of carbon emissions. The transition to electric vehicles is still far off. The city counted just 1,700 homes powered with solar energy in 2014, a fraction of Oakland’s total residences.

PG&E, the big electric utility, says it is on the way to meeting California’s requirement to generate 33 percent of its power with renewable fuels by 2020. But the utility still relies on natural gas for 27 percent of its generating capacity, according to company figures, and operates a 600-megawatt gas-fired electrical generating station near Oakland. The Gateway generating station’s big resource-efficient statement is its low water consumption. The plant is air-cooled, which the utility reports uses 97 percent less water than older water-cooled power plants.

Gertrude Stein, the influential novelist and playwright, was raised in Oakland in the late 19th century and apparently never felt great fealty for the city. “There is no there, there,” she once wrote. Four generations later, that is no longer true.

By most measures of economic vitality, environmental quality, and civic energy, Oakland has a there, there. Because of the depth of work done to address climate change, Oakland is one of the 12 American cities selected to join the Local Climate Leaders Circle at the UN Climate Change conference in Paris in December. Mayor Libby Schaaf and 11 other colleagues will be in Paris to display the capacity of cities to limit emissions of greenhouse gases. With resolve that has largely bypassed national and international attention, Oakland is purposefully reworking its operating strategy, developing new standards of resource efficiency and pollution prevention, and prospering in the new century’s treacherous ecological and market conditions.

As part of our Global Choke Point project the China Environment Forum, a program of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and Circle of Blue are closely studying trends in energy and water supply and use in two Pacific port cities – Oakland and Shenzhen, China. This story is the second in a two-part series on Oakland. Read the first part here: In Oakland, Still A City With Thorns, A New Garden Emerges (Part I). The Choke Point: Cities project builds on five years of multimedia reporting and convening that examined the water-energy-food confrontations in China, Australia, the United States, India, Mongolia, and the Arabian Gulf.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider