Lake Ontario Water Level Plan Tests Attitudes Toward Environment

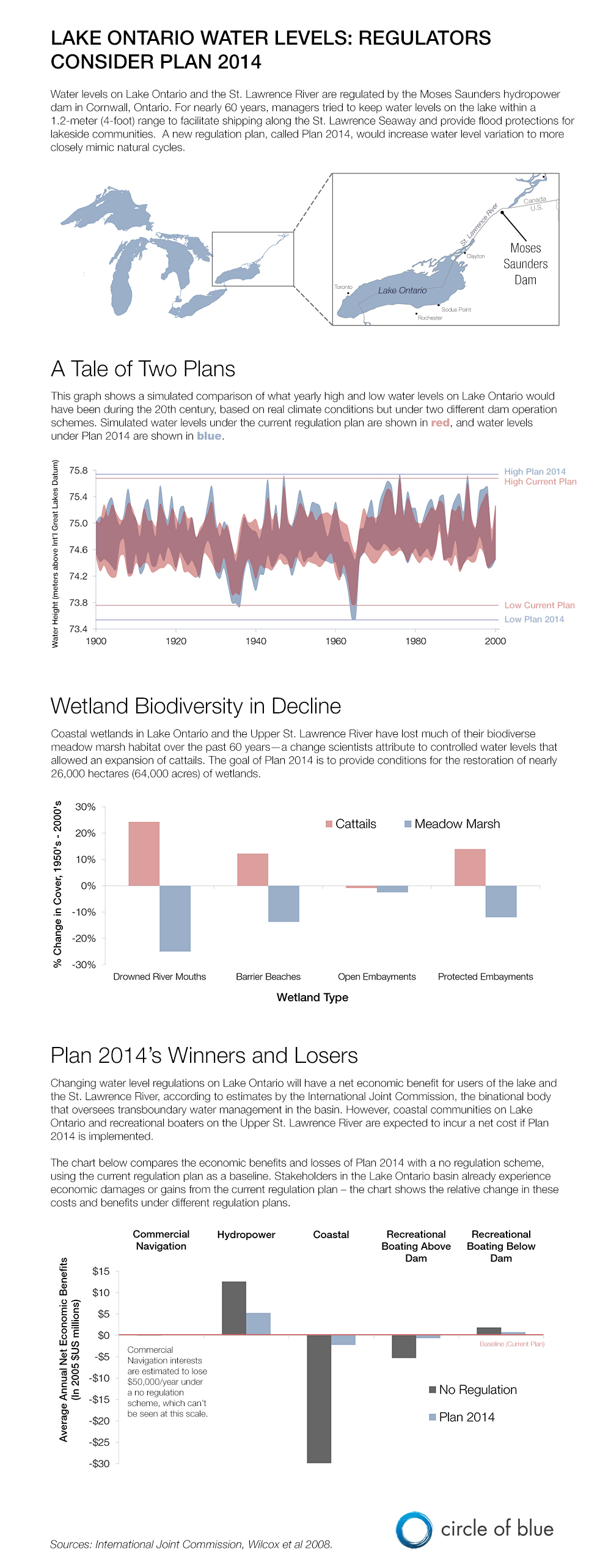

Plan 2014, a proposal to alter lake levels and restore wetlands, places ecosystems at the heart of decisions.

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

CLAYTON, N.Y.— All the force of the Great Lakes—the largest system of fresh surface water in the world—rushes into the St. Lawrence River and shatters the land into spangles of forest, mist, and water. This is the Thousand Islands region, a labyrinth of more than 1,800 islands where 226-meter-long (740-foot-long) freighters nose their way along the St. Lawrence Seaway into the heart of North America.

The river rolls past the castle homes of 19th-century millionaires and wends through leafy coves and expanses of shallow marshlands. But what appears as a thriving and verdant natural haven is in reality a landscape under assault.

Lee Willbanks pilots his boat along the shores of Grindstone Island, the fourth largest island in the St. Lawrence, and points to a wetland in Flynn Bay. It is a mass of waving cattails, as close together as bristles on a brush and as uniform as a field of corn. Absent are the sedges and grasses, the rushes and meandering water channels that provide food and shelter for birds, fish, and mammals.

The state of Lake Ontario wetlands is they have all been invaded by cattails.” —Doug Wilcox, Professor of Wetland Science, SUNY College at Brockport

“When somebody who doesn’t know the issue goes and stands and looks at a wetland area, and it’s a monoculture of green cattails, it still looks alive, it still looks vibrant, and it’s not,” said Willbanks, who serves as the executive director of Save the River, the Upper St. Lawrence Riverkeeper in Clayton, New York. “Where you once had channels that spawning fish could go up into, you have nothing but a lot of cattails. They bump their noses on it, they release their eggs in the deeper water or they spawn in inappropriate places. I mean it is a visual, immediate thing.”

Biologists trace the decline of the region’s wetlands to events more than half a century ago. In 1958, 165 kilometers (102 miles) northeast of Clayton, the United States and Canada opened the Moses Saunders power dam. At 2,000 megawatts, it was one of the world’s largest hydropower projects at the time. The dam, spanning the two countries across the vast watery tract of the St. Lawrence River, was built to fuel the adolescent but rapidly maturing economies of New York and Ontario and would also form a key control point for water levels along the newly constructed St. Lawrence Seaway. And regulators, still raw with the memory of Hurricane Hazel’s ruthless floods four years earlier, granted one other concession: a promise to keep water levels in Lake Ontario, as nearly as possible, within a 4-foot range and thereby ensure a measure of flood protection for lakeside homeowners.

The cost, unintended but also unconsidered, was the health of wetlands like those in Flynn Bay. In their eagerness to tame the 14th largest lake in the world and streamline one of the largest rivers in North America into an efficient marine highway and energy source, the two countries tipped water conditions in favor of the innocuous cattail—a native plant that, in the past, was kept in check by the Great Lakes’ fluctuating water levels. Regulating the lake’s water levels largely cut out low water years, keeping Lake Ontario artificially high and squelching the opportunity for the seeds of other wetland plants to germinate.

Seasonal water levels changed too, with managers drawing the lake lower in the fall to accommodate spring snowmelt. This deteriorated conditions for two keystone species—muskrat and northern pike—by forcing muskrats to abandon their winter dens and making it difficult for northern pike to reach their spawning grounds in the spring, explained Doug Wilcox, a professor of wetland science at SUNY College at Brockport who researches Great Lakes wetlands.

Over the ensuing 60 years, biologists estimate that crucial biodiversity has been lost across nearly 26,000 hectares (64,000 acres) of coastal wetlands along Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River as cattails take over areas that were once diverse meadow marshes.

“The state of Lake Ontario wetlands is they have all been invaded by cattails,” said Wilcox in an interview with Circle of Blue.

Now, faced with a growing body of science documenting the benefits of healthy, intact wetlands—including improved water quality, stronger fisheries, and erosion control—Canada and the United States are contemplating a plan to place the environment at the center of decisions about water level regulations on Lake Ontario. The proposal, called Plan 2014, aims to restore the lake’s coastal wetlands by increasing the variability of water levels to mimic more natural fluctuations. It is the culmination of more than two decades of research and deliberation, a $US 20 million binational study, and a procession of earlier plans evaluated and discarded in the quest for a perfect balance between shipping, hydropower, municipal, recreational, residential, and environmental interests.

If it is adopted, Plan 2014 would reflect a seismic shift in thinking about how water should be used and valued that first took root during the environmental movement of the 1960s. In the heart of the 20th century, the architects of major infrastructure projects like the Moses Saunders dam and the St. Lawrence Seaway spared little concern for sedge grasses, waterfowl, and fish. But the 21st century, rife with erratic and severe weather, burgeoning populations, and dwindling resources, is putting immense pressure on regulators and managers to reimagine how humans and natural water systems coexist.

The result is manifest around the world—in efforts to safeguard California’s San-Joaquin Delta, reconnect the Colorado River with the sea, and keep more water in Australia’s Murray-Darling River system—and the shakeup is not without casualties. As California runs dry, cities and farmers south of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta are decrying the amount of water being saved to protect the endangered delta smelt, a 10-centimeter long fish. In the Murray-Darling Basin, farmers have pushed for stricter limits on government efforts to buy water for the environment.

Largely the commission felt that, yes, not everyone would be happy. But it was impossible to make everybody happy.” –David Fay, Senior Engineer, International Joint Commission

Submitted last year by the International Joint Commission, the binational body that oversees transboundary water resources, Plan 2014 has been awaiting approval from both the Canadian and American federal governments ever since. Its release was met with unusual silence from Governor Cuomo of New York, where much of the plan’s influence would be felt, and the U.S. State Department has been equally mum. Supporters worry that, with Canada’s government in transition following federal elections on October 19 and the United States ramping up its own political machine ahead of presidential elections next fall, the window of opportunity for passing the new regulatory framework is closing.

Plan 2014 Mired in Bureaucratic Process and Civic Discontent

That leaves Plan 2014 –a blueprint that would alter the control regime for an entire Great Lake, could foster one of the largest wetland restorations in North America, and could inflict millions of dollars in damages to shoreline property—quietly stuck in bureaucratic limbo.

On the U.S. side, the plan is stuck in the Department of State. A department spokesperson told Circle of Blue that numerous federal agencies are considering the proposal, but there is no set timeline for a response. Across the border, its fate rests with Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development. There is little indication that either government will approve or deny the plan anytime soon, and, by default, water level regulations remain as they have for the past 57 years. In addition, the state of New York has yet to make a determination in favor of or against Plan 2014.

“Governor Cuomo, he’s very quiet about the whole thing, he hasn’t spoken one way or another about it because it’s a hot potato,” Chris Tertinek, the mayor of Sodus Point, New York, on the south shore of Lake Ontario, told Circle of Blue. “And I don’t think he wants to get into it—which I don’t blame him.”

“I would like the governor to take a side on it, one way or another,” he added. “The governor, although he does not have veto power, if he said we don’t want to have it, then the State Department most likely will not go with it. So he has a tremendous amount of influence.”

Meanwhile, a bitter debate has ensued between homeowners on the south shore of Lake Ontario, the IJC, and environmental groups pushing for the plan’s implementation. IJC engineers contend it would represent a relatively small change from current water level operations, but both proponents and opponents say it will doubtless inflict damage on some communities—though they disagree on the amount and equity of those damages. What Canada and the United States must weigh is to what extent they are willing to sacrifice human interests in the name of environmental restoration and a chance to alter a development paradigm built not to accommodate nature, but to tame it. The tradeoffs are a reality that the International Joint Commission acknowledges.

“Largely the commission felt that, yes, not everyone would be happy,” David Fay, senior engineer for the IJC in Ottawa, told Circle of Blue. “But it was impossible to make everybody happy.”

A Contentious Plan to Restore More Natural Water Levels

Current orders governing the release of water from the Moses Saunders dam are designed to make sure there is enough water in the St. Lawrence River to ease the passage of ships navigating the St. Lawrence Seaway, while still protecting homeowners and boaters on Lake Ontario. To do so, they stipulate that average monthly water levels on Lake Ontario should not fall outside a 1.2-meter range (4 feet) from high to low, though the lower limit is only in effect from April through November. In comparison, natural water levels recorded prior to regulation varied by about 1.8 meters (6 feet), according to the IJC.

Plan 2014 is meant to mimic natural variations in water levels and so does not specify a set range of high and low water marks. It instead relies on a collection of trigger levels that change depending on the time of year to mirror seasonal fluctuations in water level. The International St. Lawrence River Board of Control, an entity created by the IJC in 1952 to manage water levels on the lake and river, would only take action to significantly lower or raise water levels on Lake Ontario when one of the trigger levels is reached—a departure from current practices that allow the board this discretion at any time.

The triggers, however, are not a floor or a ceiling for Lake Ontario water levels. Instead, they represent the point at which the Board of Control is allowed to deviate from Plan 2014 in order to protect stakeholders such as shipping interests, municipal utilities, shoreline homeowners, and recreational boaters. As a result, water levels could and likely will go above or below the trigger points, according to Frank Sciremammano, a Rochester-based engineer who has served on the Board of Control for 20 years.

“Generally now, if we’re approaching the upper or lower end, the board takes discretionary authority to try to bring it back so it doesn’t last very long,” Sciremammano said in an interview with Circle of Blue. “But depending on the time of year, it’s very hard to respond, and it’s also a slow process to bring the lake down or up because of the constraints in the river. So the bottom line is that, at least now, some discretionary action can be taken when the extreme levels come. Under the new plan, the board would be constrained.”

While the constraints on the Board of Control are concerning for shoreline communities, where some homes could be flooded at the highest trigger level, they are encouraging for wetland restoration—especially if the board decides to allow water levels to dip further than the lowest trigger level.

“Ideally, under Plan 2014, when we have a period of low water supplies that would allow the lakes to be low, Plan 2014 would let it happen,” Wilcox said.

Due to instances of extreme water levels over the past 50 years that were not accounted for when the current regulation plan was designed, such as those experienced during low-water times in the mid-1960s and high-water years in 1973 and 1993, water levels have already escaped the confines of the 4-foot range. Since 1960, water levels have been above the current high-end water limit for 14 months.

The people that live here, they have basically, for the last 60 years, been planning and building according to the present levels.” –Chris Tertinek, Mayor, Sodus Point, New York

Simulations completed by the IJC show that water levels under Plan 2014 would rarely go beyond the extremes experienced under current regulations, with the highest levels under Plan 2014 only 6 centimeters (2.3 inches) greater than the highest levels recorded—though significantly higher than the top end of the 4-foot range. In exchange, the IJC asserts that the added variability would herald one of the largest wetland restorations in North America, requiring a modicum of political will.

“There’s no capital cost at all; it’s just telling the people running the computer program, ok switch from one to the other,” the IJC’s Fay said. “They’ve already done all the coding; they’re prepared for that. The costs and benefits would be to the interests, and that would largely depend on what the climate is.”

South Shore Communities Hit Hardest By Plan 2014

In the haze of a late summer day, the town of Sodus Point appears as wholesome and inviting as apple pie. Plump green baseball diamonds nudge up against the town’s main street, a spit of land reaching into Lake Ontario’s Great Sodus Bay and edged on either side by a huddle of marinas, restaurants, and t-shirt shops. Families stroll along the cozy harbor next to planters spilling over with purple petunias, and children splash into the bay’s languid water with yelps of glee.

Since 1958, shoreline communities like Sodus Point have struck a delicate bargain with Lake Ontario, and residents here are not comforted by the IJC’s projections.

You can’t hold one group or one area harmless and have all the damages in another area. It’s just not fair, and it’s really reneging on their political promise.” –Frank Sciremammano, U.S. Member, International St. Lawrence River Board of Control

The south shore is susceptible to more erosion and storm damage than other areas of the shoreline because of the way winds and currents move water around the lake and because there is more coastal development. Communities along this backstretch of New York, along with those across the lake in Ontario, are also the only stakeholder group that will have a net economic cost if regulators switch to Plan 2014, the IJC found. Recreational boating above the Moses Saunders dam could lose an estimated $US 680,000 on average each year, according to the commission’s estimates, but benefits downriver from the dam are expected to provide an overall boost to the industry of $US 100,000 annually. Estimates place average annual damages to coastal properties around the lake at $US 20.37 million under Plan 2014, about $US 2 million more than the estimated cost under the current plan.

The vast majority of the damages—86 percent—would be to sea walls and other shoreline protections, not to homes, according to the IJC. But those numbers do not include shoreline protections on Lake Ontario bays, which the IJC says are less susceptible to waves, and they underestimate damages to public property and infrastructure like parks, boat launches, and sewage lines, according to Sciremammano.

Moreover, residents along the St. Lawrence River downstream of the Moses Saunders dam are not being asked to give up any level of flood protection under Plan 2014, a shift from earlier versions of a new regulation plan the IJC first proposed in 2007. The reason is that the goal of Plan 2014 is to increase water level variability and restore ecosystems on Lake Ontario, not downstream where water levels already fluctuate more and wetlands are relatively healthy, according to the IJC’s Fay.

“The bottom line is, you also have to distribute the damages,” Sciremammano said. “You can’t hold one group or one area harmless and have all the damages in another area. It’s just not fair, and it’s really reneging on their political promise.”

Part of the problem stems from the development of businesses and homes that have come to rely on the set range of water levels laid out under the current regulation plan. In places along the south shore, houses are so close to the lake that their decks hang over the water like springboards. The IJC points out that the 4-foot range is a set of guidelines that have been exceeded in the past regardless of regulators’ efforts—meaning that home and business owners already need to deal with extreme water levels—but communities worry that Plan 2014 would increase the duration and frequency of the times they are at risk.

“The people that live here, they have basically, for the last 60 years, been planning and building according to the present levels,” Chris Tertinek, the mayor of Sodus Point, told Circle of Blue. “Now, all of a sudden they’re going to change the level and all the stuff that was built over the last 60 years is in jeopardy now, especially in the low areas.”

Because of the sandy soil in areas of Sodus Point, including the town’s namesake peninsula, higher water levels could still cause flooding even if residents build higher shoreline defenses, according to Tertinek.

“There’s very little we can do as far as protection,” Tertinek said. “You can protect a certain amount to keep the erosion down, but there’s nothing you can do to keep the flooding down.”

The fact of the matter is we know in 2015, as much as we knew when we started this in 1999, that the environment and the health of the environment is key to the health of the communities along the water.” –Lee Willbanks, Executive Director and Upper St. Lawrence Riverkeeper, Save the River

Plan 2014 does not offer any form of assistance—financial or otherwise—to help shoreline property owners or any other stakeholders in the basin mitigate the effects of higher or lower water levels. The IJC, created solely to facilitate studies and decisions about international water management, has neither the authority nor the resources to form a mitigation program. It did, however, give examples of methods used on the Canadian side of Lake Ontario to reduce flood risk—namely government programs to purchase private properties along the lake and convert them to public land. Wider beaches and small dunes that provide shore protections and have disappeared on Lake Ontario under current regulations could also rebuild during low water times under Plan 2014, but the IJC cautions that this may not occur where shorelines have already been hardened with sea walls.

“Basically what they’re saying to people is, we don’t want you on the shoreline and we’ll just flood you out to get rid of you,” Sciremammano said.

But Save the River’s Willbanks and other proponents of Plan 2014 insist it will provide benefits far beyond the confines of coastal wetlands.

“The fact of the matter is we know in 2015, as much as we knew when we started this in 1999, that the environment and the health of the environment is key to the health of the communities along the water,” Willbanks said. “To continue to deny this is just wrong.”

“One thing that happens when it goes on so long is that people begin to move to other issues,” he added, citing the Canadian and American federal elections. “We’re at a real point in time where we need to focus everybody’s attention on this and get it resolved before we have to go through a whole other process of education.”

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!