Oakland’s Web of Waters Shapes New Economy, Civic Energy

A nationally significant program of storm water management daylights streams, renovates a centerpiece lake, restores an estuary, and empowers a West Coast city.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

OAKLAND, Ca.— In March 1999, not long after he was sworn in as the 47th mayor of Oakland, Jerry Brown called Lesley Estes, the supervisor of the city’s watershed protection program. Brown, who is now California’s governor, wanted the city staffer he called “Creek Lady” to describe the most formidable ideas she had to conserve natural areas, make parks more beautiful, and clean up the city’s waters.

A healthy portion of Brown’s comeback campaign for mayor in 1997 included avante garde ideas about economy-strengthening ecology that had distinguished all of his political career. “I see Oakland as an ‘ecopolis’ of the future – a city that is both in harmony with the environment and in harmony with itself,” he told supporters.

One of the most important tools for accomplishing that feat was to understand the role that the city’s abundance of fresh water could play in what Brown called “transforming the urban space.”

It was not an entirely new thought. By the late 1990s, other cities across the country had recognized the economic value of restoring ecological resources, particularly water. New York was busy purchasing forestland in the Catskill Mountains to safeguard its major clean water reservoirs, a $US 1.3 billion project that replaced the need to build a $US 6 billion water treatment plant.

Pittsburgh was rebuilding its parks and shorelines along the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, the start of a downtown revitalization that jump-started the city’s revival as a high-tech design center. Chicago rebuilt its Lake Michigan waterfront to feature restored parks and a lengthy shoreline bicycle and running trail.

Clean Water As Economic Driver

These and many more water-related urban projects anticipated the powerful shift in the operating strategies of American cities. In the 20th century, pollution, highways, and various public policies that encouraged suburbanization drove Americans out of cities and turned what was left into sanctuaries for parked cars, downtowns that died at dark, and isolated islands for the poor.

In the 21st century, urban leaders have refocused on reviving the quality of life and attracting skilled workers. Infrastructure investments have stressed replacing concrete with natural features like restored streams and accessible parks, and more recently addressed clean air, energy efficiency in new housing, transit, and reducing climate changing emissions.

Oakland has become a national leader in all of this. Mayor Brown and Estes had big roles.

Brown, who had lived in Oakland for five years prior to the campaign, understood the city’s opportunity and the reputation for innovation displayed by its watershed protection director. Fifteen creeks flow from the Oakland foothills. Estes, a native of Palo Alto and a city worker since 1992, was building support for a state-of-the-art program to replace the 20th century use of those streams as ugly, concrete-burdened stormwater drains with 21st century restoration and pollution prevention principles.

The natural functions of the city’s creeks, she asserted, needed to be restored by demolishing concrete culvert straitjackets and rebuilding vegetated banks.

A Day With The Mayor

Brown wanted to learn more about what Estes was up to. She was overjoyed that he called.

“The mayor approached me at the beginning of his term,” Estes said in an interview. “He knew I was the stormwater manager and he fondly called me, ‘the Creek Lady.’ I was the person responsible for all regulatory compliance and restoration of creeks in the city of Oakland. I’m not sure he ever knew my name.

“He asked me to spend the day with him to show him the craziest ideas about creeks in Oakland. I took him to various sites to show him crazy ideas that I thought would never pass muster.”

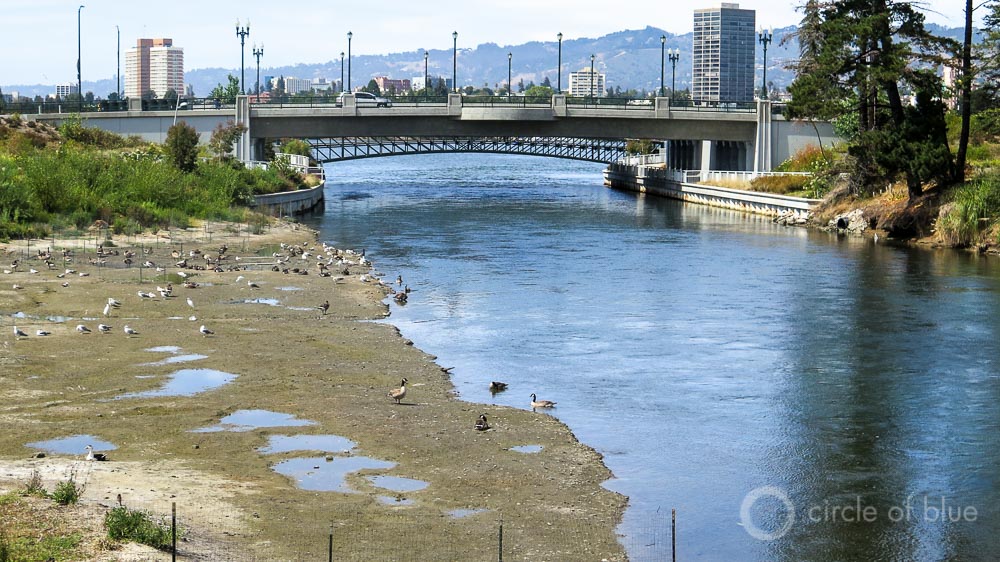

At one point, Brown and Estes, accompanied by Dharma, the mayor’s black lab, toured the outlet for Lake Merritt, the 62-hectare (154-acre) tidal lake that has served as Oakland’s Central Park since soon after the city was incorporated in 1852.

The last century was cruel to the tidal channel that joined the lake with San Francisco Bay. A series of culverts constructed beneath roadways built on causeways of dirt and rock acted like dams, constricting the flows of fresh and sea water. Lake Merritt’s oxygen levels were low. Its waters had a foul scent. Its surrounding walking paths and grass knolls attracted vagrants. Nearby neighborhoods languished.

Estes told Brown that Lake Merritt was the city’s top candidate for an ecological revitalization that would recharge Oakland’s neighborhoods and its reputation as a choice place to live.

“I said that we should open up the estuary to Lake Merritt,” she said. “It was an idea bandied about by people for many years. You have to understand that the whole area was devoted to roads and cars. We’d have to redesign everything that was there. It was so far-fetched to open up all the culverts and have better connection between Lake Merritt to San Francisco Bay.”

Brown was intrigued though. Several months passed until Estes learned the mayor had found a pool of money from the city’s port to finance feasibility studies. In 2001, Brown led the work to write a city-financed $US 198 million bond, to be voted on by city residents and paid for by a modest property tax increase.

A Public Fund For Clean Water

Half the money for the Safe Parks and Clean Water bond proposal would open the Lake Merritt channel, redesign streets around the lake to limit vehicle traffic, and revive the park. The other half would be invested in restoring creeks, preserving natural areas, improving shoreline parks, and other water-related projects.

The bond proposal was a political smash, passing with an 80 percent super majority. The program’s priorities were decided with the help of citizen oversight groups, who have also been ardently involved in planning and executing dozens of projects undertaken with public funds over the last decade.

The city designed the bond to serve as seed money to leverage federal and state dollars for projects. In many cases a dollar spent from the bond attracts three more from other funders.

In the city’s Dimond Park, for instance, the city is undertaking a $US 4 million project to demolish 228 meters (750 feet) of concrete pipe and broken concrete culvert that has contained Sausal Creek for more than half a century. Just $US 1 million of the cost is from the clean water bond. The project also involves grading the banks and planting native trees and bushes.

An inkling of what the struggling channel will look like is just upstream, where Estes’ program 12 years ago turned an equal length of concrete-jailed Sausal Creek into a bubbling brook accompanying a forested trail up into the Oakland hills.

“It’s beautiful now,” said Estes. “But these are hard projects that involve change that can be difficult for people. A restoration project takes 12 years to fill in vegetation. Spillways and check dams need to be removed. When the projects are in construction it’s very destructive. We go in with bulldozers. It’s hard to envision at the time of restoration that it will ever be great. But now we can see. It turned into something fantastic.”

Strong Support

Except for two instances when groups protested the cutting of trees to make room for improvements – one lawsuit to halt tree removal around Lake Merritt was dismissed in 2007 by a county judge – city residents have largely expressed strong support for the clean water work occurring all over Oakland.

In 2010, the city invested $US 500,000 in clean water bonds to fund an $US 800,000 project to purchase private land to conserve Butters Canyon, a remarkably wild and steep natural area. The balance was raised by residents living in and near the canyon.

Estes helped supervise the redesign of Lion Creek, diverting the flow from a concrete culvert used for controlling floods into an artificial wetland that holds the creek’s flow in a tangle of native water-loving plants. The new wetland is the centerpiece of an affordable housing project close to a stop on the BART rail transit system and within eyesight of Oracle Arena, home of the 2015 NBA champion Golden State Warriors.

“There’s been a real change in ideology about how to deal with storm water,” Estes said. “Before we started taking a holistic approach, the goal was to get the water out of here as fast as possible. Cities did that with concrete. That’s traditional engineering. We found over time that it harms water quality. Concrete doesn’t last forever. It breaks apart and causes safety hazards.

“In 1997, when I started the program, managing stormwater quality was a new field. Storm water is ubiquitous. It falls everywhere. On the street. Rooftops. It flows along impervious surfaces and picks up pollutants – all the oils and chemicals and material on the ground – and carries them directly to the stream.

“So what do we do about those pollutants? We started with best management practices – carwashes hooked to the sanitary sewer, and asking industries to keep their sites clean. We also started asking people to change practices. Pesticides. Fertilizers. Dog poop. Now we’re keeping trash and PCBs from getting into the bay.

“We also found that if we filter storm water through natural landscapes, the natural landscapes remove a lot of the pollutants. That’s the emphasis now. Drain rooftops into rain gardens. Creek restoration is an element. If we can build natural creek buffers, and have that water process through the buffer, we really improve water quality.”

Beautiful Lake Merritt

As a result of the water bond, Lake Merritt is a different place. A boathouse and other historic structures have been renovated. New bridges have been built for pedestrians and old culverts have been removed. The lake’s channel to the bay is close to being fully restored. Grassy lawns have replaced concrete roadways. The lake’s waters are cleaner. Lake Merritt’s restoration is part of the reason that Oakland’s population has grown to nearly 414,000, the highest in its history.

“The traffic is slowing,” said Richard Bailey, former director of the Lake Merritt Institute, a non-profit citizen group that helps keep the park clean. “Swales have been built to capture runoff so it doesn’t go into the lake. We’re seeing higher tides and lower tides because removing culverts allows more tidal flow to come.

“The lake’s improvement is part of the renaissance that Oakland is undergoing. We’ve seen a definite upgrade in the neighborhood. We’re finding champagne bottles instead of bottles of rot-gut. We find a lot of pacifiers now.”

On June 17, the city built a stage on the western bank of Lake Merritt and hosted a rally to celebrate the Warriors’ NBA championship. A million people, said Estes, attended the celebration on a pitch-perfect, sunny Bay Area day.

“It was fantastic,” Estes said. “We bring a million people to Oakland, to Lake Merritt. The rally happened at that very place where Jerry Brown and I talked some 16 years ago. It was a different place then. It was a mini-freeway where nobody wanted to go. Now there’s a lovely park and an open estuary. Lake Merritt now is all about bikes and pedestrians and recreation. It’s a gathering place for this community.”

As part of the Wilson Center and Circle of Blue’s Global Choke Point project, Choke Point: Port Cities will examine how Oakland, California, and Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, are responding to interlinked water, energy, and pollution challenges. These multimedia reports are meant to inform exchanges and convenings in 2016 to share among leaders of both cities and others like them around the Pacific Rim.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider

Michigan Pipeline Task Force Sets Stage for Line 5 Closure

Michigan Pipeline Task Force Sets Stage for Line 5 Closure

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!