Toxic Algae Flourish As Everglades Solution Eludes Florida

The blooms plaguing coastal estuaries are a symptom of a system out of balance.

The Landsat 8 satellite captured this image of a blue-green algae bloom in Florida’s Lake Okeechobee on July 2. Blooms of the algae are causing ecological and economic damage downstream in the St. Lucie estuary. Photo courtesy Joshua Stevens / NASA Earth Observatory

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

In the late June heat and as federal managers released phosphorus-laden water from Lake Okeechobee, the rivers and lakes of Florida’s St. Lucie estuary turned virulent green with algae. The noxious blooms have since clogged marinas and closed beaches, forcing Gov. Rick Scott to declare a state of emergency in four counties over the past week and to plead with the Obama administration to declare the region a national emergency.

The unsightly muck is the most recent manifestation of a recurring water quality menace in South Florida. Estuaries east and west of Lake Okeechobee along Florida’s Atlantic and Gulf coasts now regularly succumb to algal blooms, often with severe ecological and economic consequences. Blooms in the past five years have been linked to the decimation of critical sea grass beds in the Indian River Lagoon and to manatee deaths near the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. In communities along the Treasure Coast, where blooms are amassing this year, the presence of algae cuts into important revenue streams from recreation and tourism.

What’s going on in Florida, it’s happening all around the world now.” –Bill Mitsch, Director, Everglades Wetland Research Park

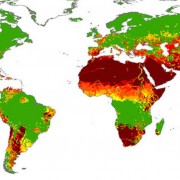

The problems in South Florida also mirror an increase in the frequency and intensity of toxic algal blooms globally. High-profile blooms are an annual occurrence in Lake Erie, where they contaminated water supplies in 2014 for nearly half a million people in Ohio, and in China’s Lake Taihu. The oxygen-starved “dead zones” that accompany large blooms of algae are spreading as well, totaling more than 400 globally. One of the most prominent, the Gulf of Mexico dead zone, is expected to cover an area the size of Connecticut this summer, according to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecast.

Both the blooms and the dead zones are triggered by excess amounts of phosphorus and nitrogen, two nutrients found in fertilizers, sewage, stormwater runoff, and industrial discharges. As agricultural production and cities expand, more nutrients are choking the world’s waterways. Warmer temperatures and intense storms linked to climate change are expected to further drive nutrient pollution and algal blooms.

“What’s going on in Florida, it’s happening all around the world now. There are too many people, too much food production, too much fertilizer on the landscape,” Bill Mitsch, director of the Everglades Wetland Research Park at Florida Gulf Coast University, told Circle of Blue. “It’s going to be haunting us for a long time.”

Florida Searches for a Fix

Releases of fresh water from Lake Okeechobee, discharged to prevent flooding, are widely blamed for causing algal blooms in the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers. Water is discharged when levels become too high to be safely corralled by the Herbert Hoover Dike, a 230-kilometer (143-mile) earthen wall surrounding Lake Okeechobee that dates from the 1930s. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which manages the dam, began releasing water to the Caloosahatchee last October, and to the St. Lucie in January after record amounts of rain fell across South Florida over the winter. Since then, it has been releasing up to 51 cubic meters of water per second (1,800 cubic feet) into the St. Lucie River, with several periods of higher and lower flows. That’s equivalent to more than 4 billion liters (1 billion gallons) each day. The lake water contains high levels of phosphorus, a key nutrient for algae, and the influx of fresh water into brackish estuaries further tips conditions in favor of algae.

The Herbert Hoover Dike is just one component of a 2,700-kilometer network of levees and canals that re-plumbed the region’s water flows.

While other factors also contribute to algal growth—water temperature, salinity, and nutrient pollution from septic tanks are all important—the releases from Lake Okeechobee are the focus of public and political ire. Residents, business owners, and lawmakers have all called on the Corps to speed up repairs to the Herbert Hoover Dike and stop the flow of water into the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee. Since 2007, the Corps has invested more than $US 500 million in projects to shore up the dike, but the timeline for improvements could stretch well into the next decade.

“Florida’s waterways, wildlife and families have been severely impacted by the inaction and negligence of the federal government not making the needed repairs to the Herbert Hoover Dike and Florida can no longer afford to wait,” Governor Scott said in a statement accompanying his emergency declaration on June 29. “Because the Obama Administration has failed to act on this issue, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers continues to discharge millions of gallons of water into the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee estuaries resulting in the growth of blue-green algae which is now entering residential waterways in South Florida.”

The governor’s emergency order directed the South Florida Water Management District, the state agency that manages water from Orlando to the Florida Keys, to store more water in the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes, before it reaches Lake Okeechobee. For its part, the Corps agreed to reduce the target water flows into the St. Lucie estuary to 33 cubic meters per second (1,170 cubic feet), and to 85 cubic meters per second (3,000 cubic feet) for the Caloosahatchee.

The Everglades Problem

But even if dike repairs eventually allow managers to store more water in Lake Okeechobee, South Florida will still face an immense water management challenge. The Herbert Hoover Dike is just one component of a 2,700-kilometer (1,700-mile) network of levees and canals that re-plumbed the region’s water flows. After flooding from hurricanes killed more than 2,600 people around Lake Okeechobee in the late 1920s, and caused widespread destruction again in 1947, Congress authorized the construction of the Central and Southern Florida Project. The project’s aim was to provide flood control to areas east of Lake Okeechobee and drain agricultural land to the south. To accomplish those goals, most of the water that once flowed south into the Everglades, sometimes in a sheet stretching 100 kilometers (62 miles) across, was kept in Lake Okeechobee and channeled east and west through the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers.

By engineering a solution to some problems, water managers created others. The result of the dike system is too much fresh water running into the rivers and their associated estuaries on the coasts, and too little fresh water making it south to the Everglades. In the estuaries, this can lead to algal blooms and harm oysters and vegetation. In the Everglades, it allows more saltwater intrusion from rising sea levels that can cause the collapse of peat soils and the destruction of wetland habitat.

The water in Lake Okeechobee is so heavily laden with phosphorus from farms, cities, and septic runoff that it is too polluted to risk sending to the Everglades.

The solution, then, seems obvious: allow water from Lake Okeechobee to flow south to the wetland as it used to do.

“The basic concept is the water should flow north and south,” said Mitsch. “The diversion east and west really brought in a whole other set of problems that they hadn’t anticipated, or maybe they had but thought they could get away with it.”

But in a twist of ecology, the water in Lake Okeechobee is so heavily laden with phosphorus from farms, cities, and septic runoff that it is too polluted to risk sending to the Everglades, where plants and animals are adapted to extremely low levels of the nutrient. Higher levels of nutrients can facilitate the growth of nuisance species such as cattail, which displaces native sawgrass.

“We have the option of getting lots of water from Okeechobee that is currently being turned loose on the St. Lucie,” said Peter Frederick, a research professor in the department of wildlife ecology and conservation at the University of Florida. “They would love for us to take that water. The only problem is it’s dirty water.”

An additional barrier is population growth. A century ago, the Everglades region was home to half a million people. Now, more than 6 million people live in major population centers south of Lake Okeechobee, including Miami, West Palm Beach, and Fort Meyers.

Restoration Slow and Difficult

The phosphorus problem has long stymied restoration efforts in Lake Okeechobee, the Everglades, and coastal estuaries. In 2000, Congress authorized the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), billed as the largest ecosystem restoration project in the world. The project is estimated to cost more than $US 10 billion and could take more than three decades to complete. Though some progress has been made, funding gaps and technical hurdles have impeded the plan’s implementation.

Chief among them is the difficulty of extracting phosphorus from the large quantities of water flowing through Lake Okeechobee. While some efforts have focused on reducing phosphorus runoff from agricultural lands in the Lake Okeechobee watershed, scientists say the legacy phosphorus contained in the lake’s sediments—as much as 300 years’ worth—would pose a problem even if farmers reduced runoff to zero. Instead, they argue that the best bet to clean the water is filtering it through large areas of constructed wetlands. This would mimic the natural functioning of the Everglades system; before the installation of canals and dikes, water could take more than year to trickle down from Lake Okeechobee through the Everglades to the ocean. Extra water storage could also help communities better withstand periods of droughts and floods, which are expected to become more severe under climate change scenarios.

We’ve got a huge amount invested in this infrastructure, in this system. With a little bit more we could make the whole thing go.” –Peter Frederick, Research Professor, University of Florida

“If that’s true, buffering is really going to be at a premium,” Frederick told Circle of Blue. “The problem we are faced with right now is that we’ve got a huge amount invested in this infrastructure, in this system. With a little bit more we could make the whole thing go.”

Finding the space and finances to build all of these wetlands, called Stormwater Treatment Areas, is yet another challenge. Florida has already constructed 23,000 hectares (57,000 acres) of STAs south of Lake Okeechobee. Last year, they treated 1.4 million acre-feet of water and reduced phosphorus by 83 percent, according to the South Florida Water Management District. The state plans to allocate $US 5 billion over the next 20 years to further implement the CERP, on top of the nearly $US 2 billion it already invested, but argues that the federal government should be paying more to help.

A water resources bill before the U.S. Senate would do that. The bill allocates $US 1 billion to the Central Everglades Planning Project, which would help rehabilitate the natural hydrology in South Florida. Both of the state’s senators support the measure as do environmental groups. Researchers say that the region, with a better ecological balance, can recover.

“It’s a hydrological mess right now, but it’s not unsolvable,” Mitsch said.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek