U.S. Dam Safety Improves But Faces Evolving Risks

No fatal dam failures in last decade, but plenty of warnings.

The remains of the Lake Delhi Dam, in Iowa, after the 59-foot-high structure failed during a heavy rainstorm in July 2010. Photo by Josh deBerge / FEMA

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

All was quiet at the Fehring house before the flood came. It was before dawn on March 14, 2006. The family was asleep, unaware of trouble upstream. The Ka Loko Dam, strained by six weeks of heavy tropical rain, was coming unhinged. Before daybreak the 116-year-old earthen barrier collapsed. Four hundred million gallons of water poured out of the reservoir on the north end of Kauai, a Hawaiian island. Seven people who were sleeping in houses on the Fehring property — including Aurora Fehring, her husband Alan Dingwall, and their two-year-old son Rowan — died in the deluge.

The Ka Loko tragedy was the most recent fatal dam failure in the United States. That no one has died in the decade since because of a collapsed dam is partly a matter of luck, experts say. A presentation in 2012 from a Maryland dam safety official was titled “Dodging the Bullet.”

Zero deaths is largely a testament to dam-safety preparations that have been dramatically strengthened. State and federal governments are doing more inspections, committing more money to oversight programs, completing emergency plans for downstream evacuations in case of disaster, and removing old dams that are too hazardous to keep standing. The efforts to reduce risk have worked.

“We are systematically better at doing this in the last 30 years,” Marty McCann, director of the National Performance of Dams Program at Stanford University, told Circle of Blue. “We’ve been successful. Not perfect, but successful.”

Still, the heightened attention to dam safety in the United States follows several recent and serious incidents of dam failures. Earlier this fall, some 20 dams were breached in North Carolina and 25 more in South Carolina in the wake of Hurricane Matthew. In South Carolina, 51 dams failed in the first week of October 2015 during record floods associated with Hurricane Joaquin.

In the decade since Ka Loko, moreover, there have been hundreds of breaks, ruptures, and failures that have swept away homes, torn up property, mangled roads, and poisoned ecosystems. The collapse of a dike in 2008 that held coal ash waste in Kingston, Tennessee released a billion-gallon toxic tide of muddy ash loaded with arsenic, lead, and other contaminants into the Emory River.

In the 1970s, dams failed and people drowned, observes Bruce Tschantz, a dam safety consultant to the Carter administration and the first chief of federal dam safety. Based on data gathered by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, at least 466 people died in dam failures during that decade. Today, authorities generally alert residents to leave before dams give way.

The nation’s fleet of more than 90,500 dams faces an evolving equation of risk. First is structural integrity. Dams, like bridges, roads, and water mains, are aging. Most are more than 50 years old, and an unknown number are not built to contemporary safety standards.

Second is shifting environmental conditions. Climate change is unleashing more powerful storms that will test a dam’s engineering.

Third is changing land uses. New housing and business development upstream is perhaps a greater near-term worry than climate change, Tschantz said. The asphalt and pavement of cities and suburbs increases runoff into reservoirs during hard rains, which can overwhelm a dam’s outlets. Meanwhile, development downstream puts more people in the path of potential destruction.

Fourth is oversight. Federal dams have attentive managers, sophisticated monitoring, and cash for repairs. But more than three out of four dams are regulated by states, where the commitment to dam safety varies considerably. Roughly one-third of the most dangerous dams do not have emergency plans to guide a downstream evacuation, according to state data filed with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ National Inventory of Dams. Nearly two-thirds of dams have private owners, such as homeowners associations that want lakefront property, who may have neither the desire nor the money for repairs.

Added up, there are two conclusions: Dam safety has never been stronger. And dam owners and regulators still have much work to do. “Things happen slowly in dams,” Tschantz told Circle of Blue. “The dam might have been there 50 years and nothing happened until now. Then boom! A tropical storm comes zipping up and you realize that the dam is not so good. We’re learning every time a major storm comes through how complacent dam programs and owners are at maintaining safe structures.”

Dam Safety Risks Are Both Familiar and Unusual

The universe of American dams is expansive. There are tailings dams that hold back a slurry of mine wastes, stock ponds for irrigation or watering cattle, and artificial lakes for sailing and speedboats. There are dams to detain flood waters and dams to filter debris. Then there are the hydropower behemoths such as Grand Coulee and Hoover, symbols of 20th-century engineering might. Though iconic, these canyon-bridging concrete plugs are the minority. Most dams are small structures less than 25 feet tall made of packed dirt and rock and built more than 50 years ago.

Surprisingly little is known about why individual dams fail. Few states do autopsies to learn precisely what went wrong. That is why McCann founded the National Performance of Dams Program in 1994. The program’s goal is to learn from past failures so that managers can identify problems before they become tragedies. McCann has found that the U.S. dam industry is far behind the nuclear power and oil and gas pipeline industries in the amount of data it collects.

Not every dam failure is judged by the same criteria. The United States has a three-tier rating system that classifies a dam based on the destruction resulting from failure. The rating system is used to set design standards; the greater the risk the stricter the codes. Low-hazard dams are expected to cause minimal property damage. McCann said that it’s acceptable if these dams, as long as they are accurately categorized, fail because the risks to life and property are low. Richland County, South Carolina notes that several of its dams will fail in a 50-year flood. Significant-hazard dams are a step up. They might destroy infrastructure or cause severe property damage if breached. The most worrisome category is high-hazard potential. A rupture at one of these dams could kill people.

A new risk on the industry’s radar is climate change but engineers are still trying to figure out how droughts and severe storms will affect dam performance.

“Climate change is not doing dam safety a benefit at all,” Tschantz said. “We know it will change risk but it has not been quantified yet.”

Eric Halpin, deputy dam safety officer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said that the key variable is how a dam’s engineering responds to sharp shifts in weather.

“We’re living off the investments of two to three generations ago,” Halpin told Circle of Blue. “Those dams have the science and engineering of their times embedded in them. The pace of change today doesn’t get easier. It gets harder in the future: back to back wettest years followed by five years of drought. All this has an impact on dams.”

The Response

Dam safety experts point to a number of actions that states and dam owners should be taking.

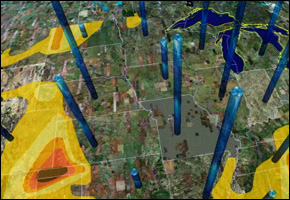

Dams should have an updated emergency action plan (EAP). These plans coordinate actions between the dam owner, regulators, emergency responders, police, and the local community. Plans organize the chain of command and establish triggers for evacuation orders. They include inundation maps that show the land that would be flooded if the dam released all its water. The Ka Loko Dam had no emergency plan.

The number of high-hazard dams with an EAP has more than doubled since 2000. “We’ve come a long way,” Tschantz said. “But [circumstances] are constantly changing. EAPs need to be reconsidered consistently.”

In 2015, California tore down the 106-foot-high San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River because the dam was at risk of collapsing in an earthquake. Photo by Kelly Grow / California Department of Water Resources

Whether a dam requires an EAP depends on its classification and state standards. Some states require a plan only for high-hazard dams. That relates to a second problem: incorrect classification. Conditions above and below dams change. Cities grow, rural land becomes a subdivision, more people move into harm’s way. The number of high hazard dams has increased by 67 percent since 1998, according to data in the National Inventory of Dams. The need for a better accounting of how upstream development magnifies floods was one of the major conclusions of a Northeastern University assessment of the South Carolina dam failures. Counties in the center of the state saw 17 to 24 inches of rain in a 24-hour period.

Incorrect classification has consequences. The Ka Loko Dam, for one, was classified as a low hazard. An independent investigator appointed by the Hawaii attorney general to review the Ka Loko tragedy determined that the hazard rating was “a mistake.” The dam was never inspected, due in part to Hawaii having only one full-time and one part-time dam inspector, fewer than the 6.5 full-time equivalent staff it should have had for the number of dams in the state.

Inspections are essential, Tschantz and others said. They reveal whether the dam is still structurally sound. Some of the biggest threats are from surprising sources: burrowing animals and tree roots that carve out a dam’s innards.

If a dam needs to be modified there are ready solutions. Increasing the size of spillways, which are used to dump water rapidly, are a “quick and efficient fix,” Jason Vazquez, senior engineer for locks and dams at Arcadis, told Circle of Blue. The main reason that Ka Loko failed is that the owner filled in the spillways and could not pass the flood.

The Future

All of these actions require money. Experts interviewed for this story said that funding is the biggest impediment for dam safety. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO), the premier organization dedicated to safer dams, estimated in 2013 that $US 18 billion is needed to repair the nation’s non-federal high-hazard dams.

Repeated for years, the message reached Congress this year. A water infrastructure bill that passed the House and Senate in early December authorizes $US 445 million over 10 years for state-regulated high-hazard dams. It is the first time that Congress has designated grant money for state dam repairs. Still, compared to the tens of billions of dollars necessary to bring sub-standard dams up to code, the outlay “just scratches the surface,” notes Lori Spragens, executive director of ASDSO.

A catastrophic dam failure, unfortunately, is often the messenger of last resort. In response to the dams that ruptured in 2015, South Carolina lawmakers voted earlier this year to increase the dam safety budget to more than $US 1 million, roughly four times higher than it was in 2014. The increase comes after years of neglect, according to Mark Ogden, ASDSO project manager. Before the big flood, South Carolina was spending about one-sixth the national average per regulated dam.

A bill to strengthen state regulatory authority, however, did not pass. Lawmakers called more regulations a burden. But after Hurricane Matthew knocked out 25 more dams this October, lawmakers are expected to revisit the issue next session, The State newspaper reports.

“The people of South Carolina can see the damage that, within a matter of hours, can be brought to this state,” said Rep. David Hiott, chairman of an advisory committee. “It’s our responsibility as legislators to provide for safety for the public and that includes dam safety.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton