Water Affordability Is A New Civil Rights Movement in the United States

Cost of water and sewer services is rising out of reach for hundreds of thousands of Americans.

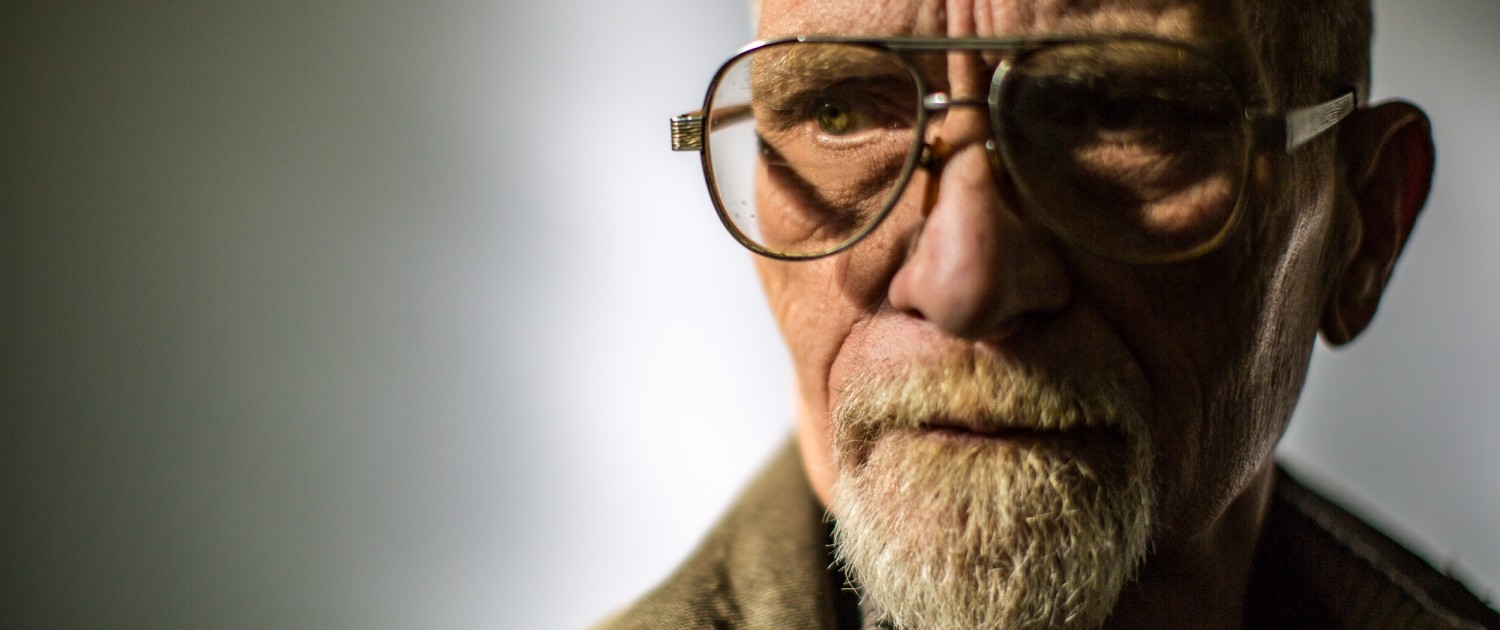

In August 2014, people rallied in Detroit to protest the cutting of water service to residents behind on their bills.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

The cost of drinking water and sewer services in the United States, rising on average at twice the rate of inflation, is giving birth to a new civil rights movement, one based on access to water and sanitation for the poor.

Stirred by the thousands of Detroiters whose water service was shut off in 2014, local groups have coalesced into a national campaign for affordable water. They seek new policies at the local, state, and federal levels to help the country’s poorest residents maintain basic services during an era of financial tumult.

The movement’s origins are local, led by grassroots activists primarily in the Rust Belt and New England. Dozens more communities around the nation that are stung by poverty, government mismanagement, or old infrastructure are also involved: the Massachusetts Global Action’s Color of Water Project, in Boston; the People’s Water Board, in Detroit; the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization; the Environmental Justice Coalition for Water, in California.

“We have gone beyond the point where water and sewer services are affordable for the poor,” says Patricia Jones, who for a decade has lead the right to water program at the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, a leader in the affordability effort that is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The water affordability movement is a symptom of a great upheaval in America’s economic and political life. Even before the 2007 recession put nearly 9 million people out of work, America’s economy was cleaving in two — wealth flowing to the savviest firms and top earners while abandoning those at the bottom, who see the costs of food, housing, medical care, and even water sprinting far ahead of their income.

The movement also is a result of a fundamental rebalancing of America’s relationship to water. Systems to treat and deliver drinking water and dispose of sewage are a rotary phone in the age of wireless communications — still functioning but not optimally. America’s urban water systems leak. They break. They are expensive. They spill wastes into rivers and onto beaches during downpours. They treat nearly all water to drinking standard, even when it is used to flush the toilet.

Systems in every state need to be modernized for a world of more powerful droughts, fiercer floods, and rising seas. Doing so will cost trillions of dollars, according to industry estimates. Yet despite the widespread societal benefits of such investment, pitfalls will arise.

The poor are already being left behind. The affordability movement wants to ensure that the next round of water infrastructure spending does not break them. Like nearly all questions of public policy, the basic question that is swirling is, who pays? And how much?

The campaign’s proposals are gaining a foothold in state and local politics. In Michigan, a state at the center of the movement thanks to crises in Detroit and Flint, legislators introduced a 10-bill water affordability package last November. Two months earlier, Philadelphia became the first big city in the country to have a water rate for the poor that is based on how much they earn.

Big Problem Brews National Coalition

The moral and intellectual foundations of the affordable water movement can be traced to July 28, 2010, when after years of debate, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution recognizing the human right to water. It was a landmark action for human rights campaigners.

Soon after, in February and March of 2011, Catarina de Albuquerque, the United Nations independent expert on drinking water and sanitation toured the United States. She released a report in August of that year that outlined the struggle to maintain clean water or sanitation in California, Massachusetts, and Maryland. She also heard testimony from citizens in Alabama, Alaska, Michigan, West Virginia, and Puerto Rico who endure similar problems.

Then on September 12, 2012, California Governor Jerry Brown signed AB 685, a bill that recognized that “every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water.” The water rights concept, initially directed at developing countries, was spreading to more affluent places.

California might seem a natural spot for such a law to take hold in the United States. The state is often at the vanguard of progressive social policy and it has tremendous wealth disparities — tech millionaires in the Bay Area and farmworkers in the Central Valley with chronically polluted water. One state, two worlds. The center of the movement, however, is to the east, in the hollowed out post-industrial cities that launched the American Dream in the beginning of the 20th century.

Flint residents are struggling with bad water and high bills. Photo © J. Carl Ganter

In cities like Detroit and Flint water access and racial justice movements have aligned. In its early 1950s post-war heyday, when it was the wealthiest city in America, the population of Detroit peaked at 1.8 million residents, more than 80 percent of whom were white. Today, Detroit’s population is 680,000 and more than 80 percent black. Forty percent of the people live in poverty. Those remaining have inherited the legacy costs of a city built for an absent 1 million people.

“Where water infrastructure is crumbling are the places without the ability to absorb the cost increases,” Stephen Gasteyer, a Michigan State University sociologist who studies water access, told Circle of Blue. “The people who were left in these cities are predominantly minorities. Where you see things falling apart are predominantly minority communities.”

It was in Detroit at the end of last May that local groups combined forces. They formed the National Coalition on Legislation for Affordable Water (NCLAWater) to advocate for changes in utility, state, and federal policies.

The groups knew the statistics: income for the top 5 percent of American households rose 60 percent between 1980 and 2014, while income for the poorest 10 percent in the same period fell, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the U.S. Census Bureau. An average water bill in some California cities represents 17 percent or more of household income for the poorest 10 percent. They saw thousands of their neighbors — 17,000 in Detroit in the summer of 2014; 8,100 in Baltimore in 2015 — cut off from water service.

“The mass shutoffs provoked the conversation,” Suren Moodliar of the Color of Water Project told Circle of Blue. They had carried buckets and handed out bottled water. They heard the arguments that water service is cheap – cheaper than cell phone bills! – and were compelled to sharpen the narrative.

Ability to Pay Going Down

The movement has earned important victories, both in advertising its cause and in changing practices.

On October 23, 2015, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an organization that helps set the human rights agenda in the Americas, held its first-ever hearing on access to water and sanitation in the United States. Representatives from the Color of Water Project, Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, the Baltimore Right to Housing Alliance, the Multicultural Alliance for a Safe Environment, and other groups described unsanitary conditions and people cut off from water.

“We have families, especially children, living and playing among raw sewage,” Catherine Flowers, the executive director of the Alabama Center for Rural Enterprise, and the leading advocate for sanitation in rural Alabama. “This is the starkest form of inequality in this nation, and a blatant violation of the human right to clean water and sanitation.”

The IACHR was intrigued. The commission granted a request for a second hearing, which will be held on April 4.

“It’s on the agenda because the IACHR wants to hear more about it,” Maria Isabel Rivero, IACHR spokeswoman, told Circle of Blue.

Practices, too, are beginning to change. Boston has a right-to-service policy stating that it will not cut water service to households with serious illness or households where the residents are over age 65. Last September, Philadelphia became the first big city to allow poor residents to pay a percentage of their income for water. Moodliar praised the measure, saying that he hopes more cities adopt it. The water would not be free, but it would be cheaper for the poor. Establishing an income-based water rate is one of the bills in the Michigan legislative package.

“We are introducing these bills because we all believe that water is a human right, and we need to protect the residents of Detroit, Highland Park, Flint, and all Michigan communities by making sure that each resident has the right to safe, affordable, and accessible water,” said Stephanie Change, a Democrat from Detroit and one of the bill sponsors.

These types of subsidies need to be a part of the conversation, argues Jason Mumm, a water rates analyst at Hawksley Consulting.

“Unless something turns around with the U.S. economy that causes wages for the groups of people at the lower end of the income distribution to rise — which is difficult to do in a short period of time — we have to look at subsidy of service costs for citizens in the urban core,” Mumm told Circle of Blue. Subsidies could come from two sources: higher rates paid by companies or wealthier customers, or local, state, or federal taxes.

A 2014 report from the National Consumer Law Center on water and sewer affordability recommended a federal grant program for low-income households, modeled after a program for energy bills.

Those solutions, however, might not be transferable. Colorado, for example, prohibits utilities from using tax revenue to fund operations. In North Carolina, cities are not allowed to use utility revenue for financial assistance.

Thinking Broadly

Assistance programs are a lifeline for the poor, but aid alone will not fix affordability, Jones and others argue. The needs are too great, the economic trend lines too divergent, the thinking about water too narrow.

The cost of clean water is shooting skyward. Cities and states already pay for more than 95 percent of it, and bigger bills are coming. Cities have not raised enough funds for repairs, preferring to delay investment under political pressure to keep rates low.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is requiring utilities to spend billions to prevent heavy rains from overwhelming sewer systems that also transport stormwater. The responsibility for cleaning up farm pollution, at the heart of a closely watched Clean Water Act lawsuit in Iowa, is being offloaded to cities or is degrading downstream waterbodies.

The country can solve its water problem by building more equipment, but only when everyone pays a fair share will the poor be protected. Forcing cities to shoulder all the costs is a subsidy to the polluters, according to Jones. “We ought to be confronted by the choices of our subsidies,” she stated.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

I too believe that water is a human right. I grew up in the Detroit area, and was back there in 2013 to fix up and sell my childhood home. I found the water bill to be absurdly low, and the quality of the water (it was Detroit water) to be very high, except for the chlorine, which I do not have at my own home. I have been a property appraiser, and I always follow water bill issues in my present community. So many people simply decide not to pay the water bill, so the bills, the delinquencies, and the penalties mount up. Water is indeed a human right, but in cities, it is very expensive to treat and pipe in and that is not a right. you can go dip water out of the Detroit River and boil it, or you can help pay to get it to come out of your tap. You should not own a cellphone if you do not pay your water bill. You should not eat in restaurants if you do not pay your water bill, or buy and smoke cigarettes. Some of this is true poverty and some of this is a choice to treat water as a public good that everybody wants and nobody wants to pay for. And yes–the baseball stadium has a huge delinquency, as do other commercial entities. What is with being allowed to skate on the bill in such an impoverished place? why don’t you people just write the check and pay the darned bill? I make a point to pay mine, and it is quite high.