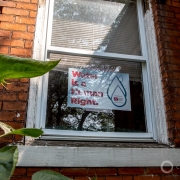

Water A Key Factor in Zika Virus Spread

Zika is carried by mosquitoes that reproduce in standing water, but in some cities that water can be hard to eliminate.

The Aedes aegypti, or yellow fever mosquito, is the primary carrier of the Zika virus. It can breed in nearly anything that holds water, from garbage to gutters, and its eggs are resistant to dry conditions. Photo by James Gathany courtesy Flickr Creative Commons

By Codi Kozacek

Circle of Blue

The World Health Organization on Monday declared the spread of the Zika virus to be a public health emergency of international concern due to its potential link to microcephaly, a birth defect that causes abnormal head and brain development. The outbreak of the mosquito-borne disease, which began in Brazil last year, is spreading rapidly through the Americas and could infect as many as 4 million people by the end of the year.

Controlling mosquito populations is paramount to stopping the outbreak, WHO said. But that proposition could prove challenging in the sprawling tropical cities where Zika has taken root. Both the Aedes aegypti, known as the yellow fever mosquito, and its relative, Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito, are capable of transmitting the Zika virus. They thrive in urban environments across the Americas and have a penchant for biting people. The mosquitoes are also active throughout the day, instead of a short window at dawn or dusk, making it more difficult to target them with traditional chemical sprays.

But perhaps the biggest challenge to eradicating the Aedes mosquitoes is their propensity for breeding in almost anything that holds water—from garbage to gutters to planter pots. Even items that do not currently contain water, but could in the future, are fair game because Aedes eggs can withstand dry periods and will hatch when water becomes available again.

“The eggs they lay are resistant to being dry or cold for some period of time,” Shannon LaDeau, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York, told Circle of Blue. “Albopictus are more resistant to cold, and aegypti are more resistant to periods of drought. They are almost like seeds that can withstand being dry and cold, which is what makes them so suitable for global dispersion. They can be moved in this egg stage large distances in a boat or in shipping containers.”

Need for Water Security Complicates Problem

That leaves city residents with the daunting task of clearing away the myriad yard items that can harbor Aedes eggs. “We need to eliminate all standing water spots, where Aedes lives and reproduces,” Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff tweeted on January 27, the same day she called for a “war” on the Aedes aegypti mosquito to stop Zika. Easier said than done. Because cities often do not provide adequate tap water, residents collect rain water in buckets and tanks for daily use. Poor public water service produces conflicting priorities, according to LaDeau.

“What the World Health Organization and other groups have acknowledged, and it’s difficult enough, is that our biggest chance of getting things under control is to have everyone take charge of their own yard,” LaDeau said. “What is challenging in some countries is that people don’t have a secure water supply, so when it rains people save water.

“There is tension between the need to get rid of all standing water and the need for people to have access to water that’s reliable,” she added.

Traditional methods to control adult mosquito populations are not as effective against the Aedes mosquitoes because they are active throughout the day, making it paramount to eliminate the standing water where they breed. Photo courtesy Malova Gobernador via Flickr Creative Commons

Outbreaks Not Inevitable

While the need for water security is less likely to be a problem in developed countries like the United States, rain barrels and planters can still provide breeding habitat for Aedes mosquitoes, which are present in many U.S. cities. The Aedes albopictus species is especially concerning because, although it does not feed almost exclusively on humans like Aedes aegypti does, it is beginning to bite humans at a much higher rate than in its native range in Asia. Because it is more cold-tolerant, it is also capable of spreading to northern cities.

Nonetheless, it takes a combination of human and environmental factors to create outbreaks of diseases like Zika, or dengue fever and chikungunya, which are also transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes.

“Things need to line up,” LaDeau explained. “To have an outbreak, someone has to carry the pathogen in. There has to be enough mosquitoes that there will be a very high probability they will bite that person. Density is very important. And then the mosquito also has to survive long enough that the probability that they bite a second person is high. Both the density and survival of the mosquitoes is directly related to weather, as well as human action.”

The prevalence of standing water is a major determinant of mosquito population density. Areas with lots of trash can give rise to large populations, for example. Sometimes populations are larger just after a drought because people have been saving water. The survival of adult mosquitoes is also dependent on factors like relative humidity and actions by humans to control them. The WHO warned that El Nino conditions this year could “increase mosquito populations greatly” in many areas.

Moreover, populations of urban mosquitoes have become much more similar across the world in the past several decades as international trade and travel increase. In the past, the species of mosquito in a given city may have been different than those found elsewhere. Now the same type of mosquito that bites a person in Tokyo could also be present in Rio de Janeiro. That enables diseases to transfer more easily across continents. Still, the mosquitoes must come into contact with an infected person to pass the disease to other humans. In some cities where air conditioning and screens are widespread, or where people stay indoors most of the time, there is less likelihood that disease transmission will occur.

“You could have a huge number of mosquitoes and an infected traveler, but still not get an outbreak because they just aren’t in contact,” LaDeau said.

A news correspondent for Circle of Blue based out of Hawaii. She writes The Stream, Circle of Blue’s daily digest of international water news trends. Her interests include food security, ecology and the Great Lakes.

Contact Codi Kozacek