2016 Preview: Brackish Groundwater Takes a Star Turn

In the perpetual search for water supplies, a salty upstart will be in the spotlight

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

It was a swift rise to fame.

In 2015, groundwater, the out-of-sight resource that supplies as many as 3 billion people with drinking water, garnered national attention because of its role in the California drought and international headlines thanks to high-profile studies on aquifer depletion and sustainability. Previously neglected by the public and policymakers, groundwater became an A-list resource.

Fresh groundwater, that is.

In 2016, brackish groundwater, a salty sibling still trapped in relative obscurity, will command center stage.

Deep droughts in recent years forced water managers to reckon with water scarcity and to diversify their water supply portfolios. Brackish groundwater is their latest target.

“There’s an interest in finding alternative water supplies,” said Jennifer Stanton, a U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist. “Freshwater is becoming more scarce.”

The coming out party for brackish water begins with science. A slew of technical investigations will be published this year, including the first national brackish groundwater assessment in a half century. Then comes development. In October, San Antonio will open the first phase of what will eventually be the world’s largest inland desalination facility.

A National Map

Brackish water is commonly defined as water with dissolved mineral content between 1,000 and 10,000 milligrams per liter. Sea water, by contrast, is more than 35,000 milligrams per liter.

The last national assessment of brackish groundwater was published in 1965. It was supposed to be a preliminary study, Stanton explained, but it collected dust and was never enhanced. That will soon change.

Stanton is leading the USGS’s efforts to update the map, which Congress requested in the 2009 Secure Water Act, a bill that authorized several studies of the nation’s water resources.

The new edition of the brackish groundwater map, which draws on 36 existing data sets, will be published in September. It assesses in broad terms the quantity of brackish groundwater to a depth of 914 meters (3,000 feet). It also identifies any chemical ions or trace elements such as arsenic or boron that would pose health risks. Three regional pilot studies have already been published, one of which found that 17 states in the central United States have enough brackish groundwater to fill the Great Lakes twice.

For all the improvements, the new map lacks the field-level detail necessary for drilling individual wells or understanding the consequences of widespread pumping, according to Stanton. She called the study a “starting point” for states, cities, and districts that are considering brackish groundwater as a new supply.

“A national study will not be able to address sustainability questions,” Stanton told Circle of Blue. “What happens if we use this resource? What will the effects be on other wells?”

Those are the sorts of questions that Texas officials are interested in.

Brackish Is Bigger in Texas

For state and local assessments, Texas leads the pack.

The Texas Water Development Board, a state agency, began its brackish water program in 2009. Of the state’s 30 major and minor aquifers, some 26 have significant brackish water resources, according to John Meyer, a TWDB geologist who runs the brackish groundwater program.

The water board is mapping water quality and availability for each aquifer. Four studies are complete and two more — of the Carrizo-Wilcox and Lipan aquifers — will be ready in the summer, Meyer said. Like DNA sequences, no two aquifers are alike. Thus the need to map them.

The Texas Legislature handed Meyer another task last year. HB 30, signed in June 2015, directed the water board to designate “groundwater production zones” for brackish aquifers and determine the amount of water that can be safely pumped over 30 and 50 years without polluting or depleting nearby water sources.

The entire assessment is due in 2022, but lawmakers asked that four aquifers of high interest be evaluated by December 1. They are the Carrizo-Wilcox, Gulf Coast, Blaine, and Rustler aquifers.

Brackish water is starting to be used in the oil and gas industry as a substitute for fresh water, but cities also have keen interest. To turn brackish supplies into drinking water the salts must be removed, often using the same membranes used to desalinate seawater. Because the salt content is so much lower in brackish water, less energy is required to cleanse it, which lowers the cost.

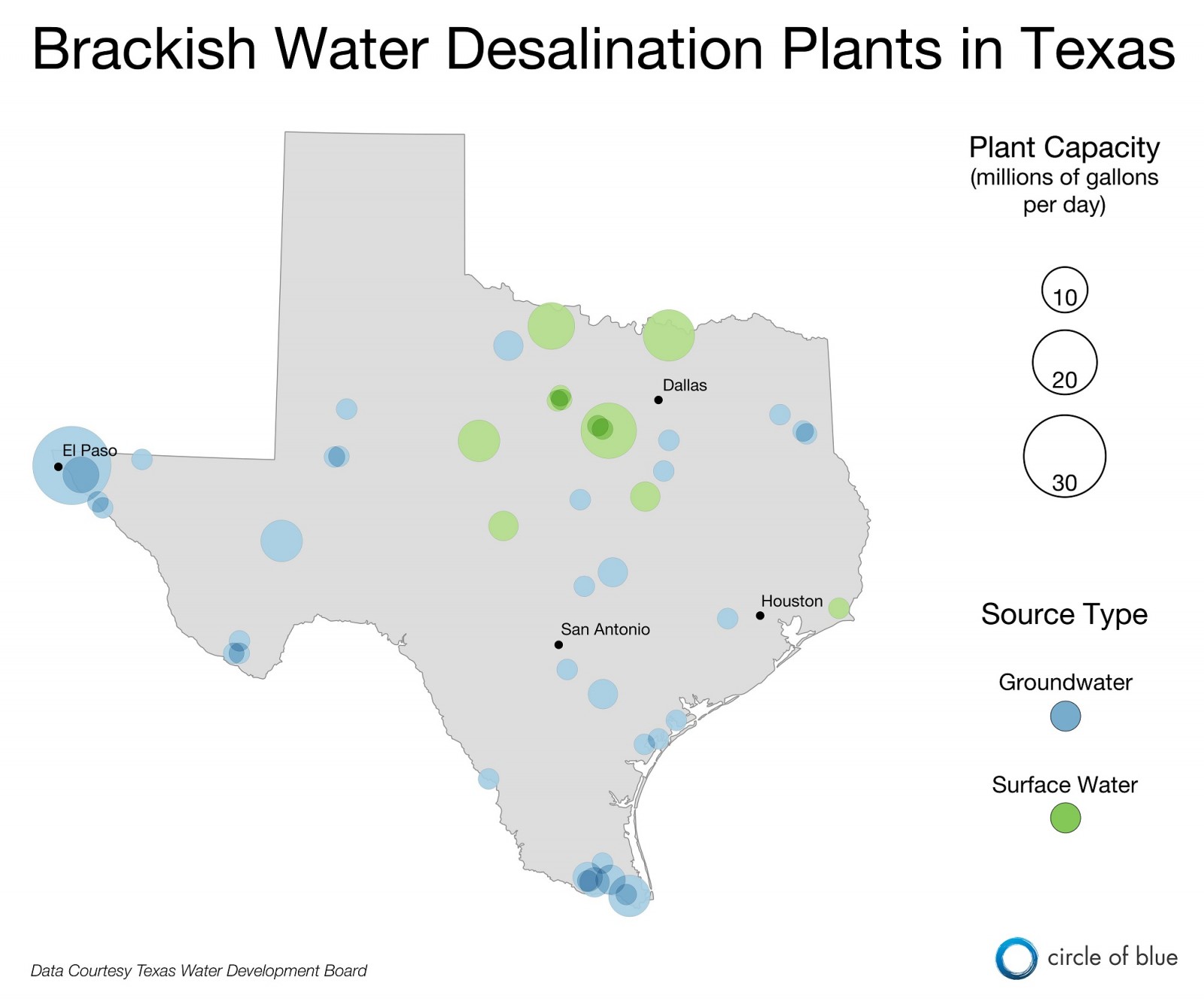

Texas already has 46 inland municipal desalination facilities that use brackish water. The Kay Bailey Hutchison desalination plant in El Paso is the world’s largest such facility, capable of producing 27.5 million gallons of drinkable water every day.

It will not be the champion for much longer, though. San Antonio is preparing to open the first phase of its own brackish groundwater desalination facility. Initially purifying 12 million gallons per day, the facility produce 30 million gallons per day when completed in 2022. (The nation’s largest seawater desalination facility, by contrast, is in Carlsbad, California. It opened in December 2015 with a 50 million-gallon-per-day capacity.)

San Antonio will begin testing phase one this summer and it will be operating in October, according to Anne Hayden, a San Antonio Water Systems spokeswoman. Because it will be the city’s first desalination plant, she said there was an initial learning curve for the public.

“A lot of people didn’t understand the concept of brackish water,” Hayden told Circle of Blue. “We started calling it ‘the salt water beneath our feet.’”

By any name, brackish water will be more well-known in 2016.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!