As Groundwater Withdrawals Increase, Jakarta Sinks

Subsidence strikes the foundations of an Asian megacity.

Jakarta is sinking as it pumps groundwater to provide drinking water for more than 10 million people.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Jakarta — home to more than 10 million people and the capital of Indonesia, the largest economy in Southeast Asia — is sinking at an increasing rate.

The head of Jakarta’s environment agency told Tempo, a news site, that the city’s land surface is dropping 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) per year on average. Groundwater withdrawals increased by 24 percent between 2011 and 2014, which is worsening the problem, Edy Junaedi said.

As water is pumped, the ground compacts like a wrung sponge. Roads, canals, and building foundations, all of which require a stable surface, can crack and shift. Coastal cities, like Jakarta, are exposed to greater risk of flooding from rising seas. With the world’s groundwater supply an increasingly urgent topic — because demand is outpacing recharge and most of the world’s major aquifers are in long-term decline — interest in the consequences of too much pumping is growing rapidly as well.

“It feels like carbon in the 1980s,” Gilles Erkens, a researcher at Deltares, told Circle of Blue at an earth sciences meeting in December 2014, referring to the decade when the study of global warming came to prominence. “It’s an exciting time, and subsidence is getting a lot of attention.”

Deltares, based in the Netherlands, is one of the world’s leading research institutions that is focused on subsidence. The organization released a report in 2014 that compared subsidence rates in coastal megacities, finding the most severe rates in the metropolises of Southeast Asia: Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila, and Ho Chi Minh City.

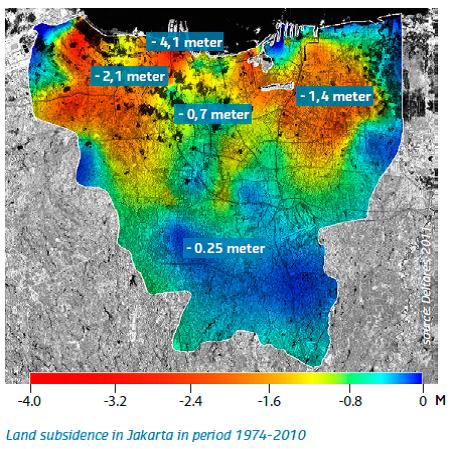

Parts of Jakarta sank more than four meters (13 feet) between 1974 and 2010. So much water was pumped from aquifers beneath the city to supply its population that the land collapsed.

“In many coastal and delta cities land subsidence exceeds absolute sea level rise up to a factor of ten,” the report states. “Without action, parts of Jakarta, Ho Chi Minh City, Bangkok and numerous other coastal cities will sink below sea level.”

In the United States, the public is most familiar with subsidence in California, where sinking soil is the final tile to fall in a series of drought-related dominoes. Dreadfully low snowpack and rainfall in the last four years prompted officials to slash water deliveries from state and federal canals. That resulted in a wave of groundwater pumping, which is causing land in the Central Valley to sink at its fastest rate ever — 5 centimeters (2 inches) per month in the summer of 2014 along the valley’s western edge.

But other areas also are affected. Houston, America’s fourth-largest city, has been wrestling with subsidence for decades. Land near Galveston Bay, the region’s industrial corridor, dropped by as much as 3 meters (10 feet) during the 20th century, according to data from the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, an agency created by the state Legislature to regulate local groundwater use.

Houston has halted the decline by transitioning from groundwater to river water. Area agencies received nearly $US 3 billion in state funding last year to aid the shift.

The Jakarta environment agency says the same course correction must occur on its home turf. The water utility plans to build more reservoirs and water treatment plants so that river water can meet new demands.

Junaedi’s advice is clear. “Stop using groundwater,” he said.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!