Projecting Global Water Supplies With A New Tool

ISciences develops predictive model for anticipating water stress.

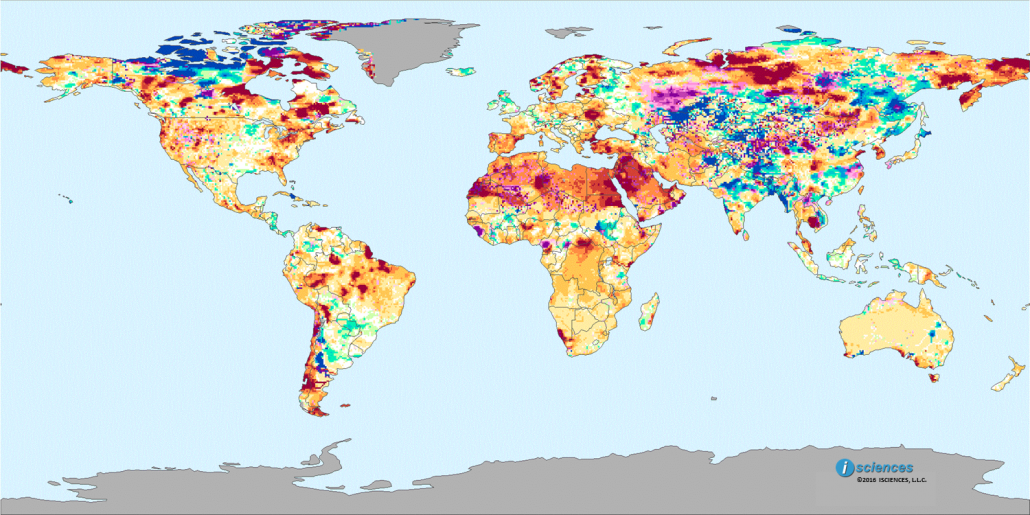

Each month ISciences updates their World Water Watch List highlighting the regions where freshwater levels are expected to rise or fall over the next nine months. Their predictions map for September 2016, shows large deficits in the Middle East with big changes predicted for Russia and Central Asia.

The profound disturbance in the planet’s water supply is linked by scientists to climate change. As the world’s weather becomes more erratic so too does predicting how much fresh water will be available for human use.

ISciences, an Ann Arbor-based research group, has set out to remedy this problem with a novel approach to predicting changes in water availability up to nine months in advance everywhere on the planet. Using the past three month’s weather patterns—combined with historic data on rainfall, soil moisture, and a host of other variables―ISciences can project with significant skill where freshwater levels rise or fall over the next nine months.

ISciences call their predictive tool the “Water Security Indicator Model (WSIM).” With it they can show where “water anomalies” occur anywhere on the earth. Water anomalies are historically significant changes to water, whether it be too much water, not enough water, or just an unusual amount of water for that region. The group’s water indicator model is capable of identifying anomalies within a 3,025 square-kilometer area (1,168 square miles)—an expanse about four times as large as New York City

The goal of the monitoring and predicting tool is to help governments, agriculturalists, and water-hungry business recognize global trends in water availability and better plan and manage water resources. .

In order to make their data more publicly consumable, each month ISciences pack their predictions into the Global Water Monitor & Forecast Watch List. Presented as a series of maps, the report highlights countries and regions around the world where water abnormalities are more likely to occur.

Their most recent watch list, published in September, has some alarming predictions.

In northern Indian, from Rajasthan extending eastward all the way to Bangladesh, water will flow freely and possibly even cause flooding, while southern India dries up. Northern Saudi Arabia will see only minor fluctuations in water quantities, easing the shortages of the past few months. But in Iraq and Iran the deficits will get worse. Kyrgyzstan will, paradoxically, experience shortfalls and excesses in water supplies.

Some of the most severe irregularities highlighted in the September report are clustered in Russia and Central Asia, where there will be too much water in some places, and not enough in others. These deficits and surpluses are trends expected once every 40 years or so in that region. Enormous swings in water availability in Russia have global consequences.

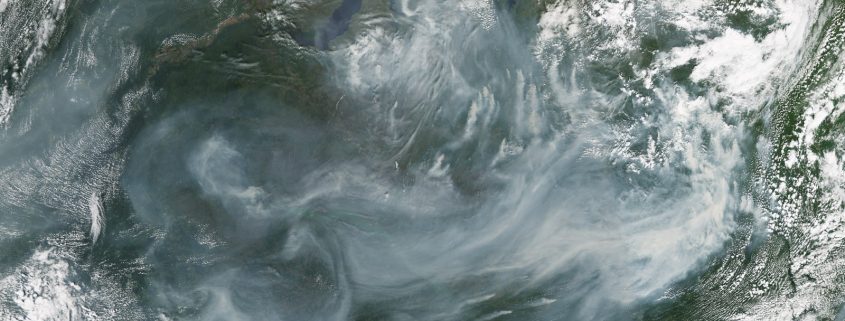

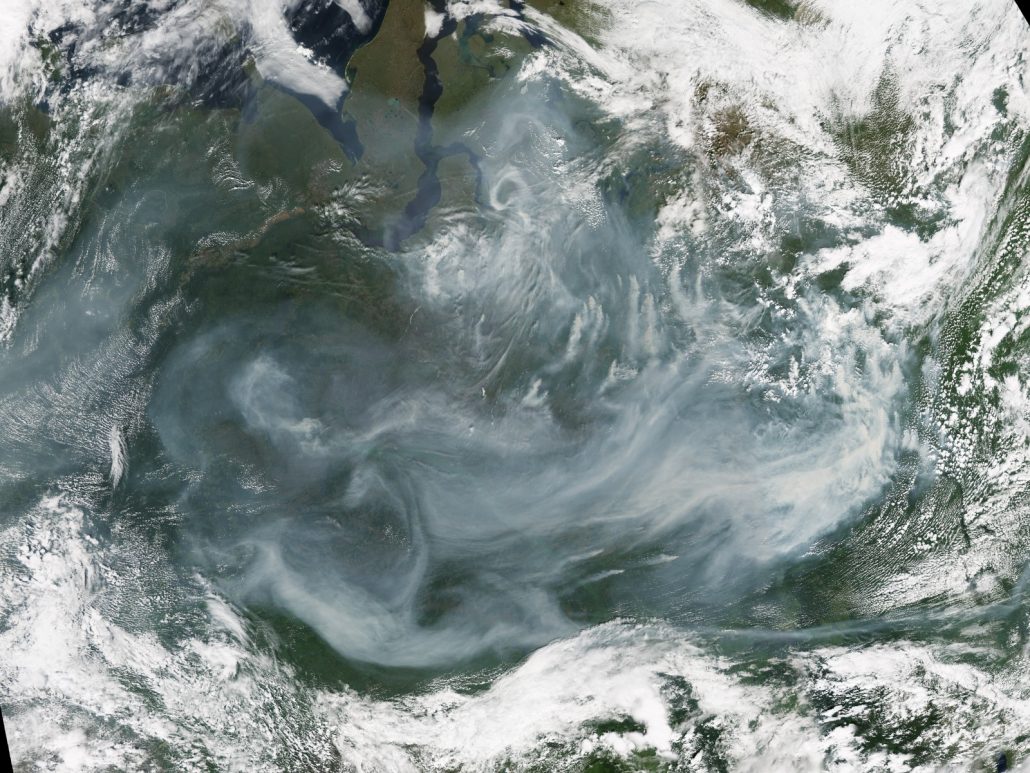

Satellite details from July 19, 2016 showing wildfires and smoke blanketing parts of Siberia. NASA/JPL

For instance, the Siberian fire season, which normally ends with summer, has extended into the fall. Exceptionally dry conditions, combined with “dry” thunderstorms—where lots of lighting is reported, but little rainfall—have combined to create one of the worst fire seasons the region has ever seen. The enormous wildfires have been spotted by NASA from space and are devastating the globally important Siberian forests, which typically absorb climate-altering carbon emissions.

Sergey Verkhovets, chair of Ecology and Environmental Studies at Siberian Federal University in Krasnoyarsk, told reporters in late September, “It seems that autumn fires and wide range of summer fires occurred due to global warming … and we expect intensification of fires in Siberia as a direct effect of climate change.”

Circle of Blue’s east coast correspondent based in New York. He specializes on water conflict and the water-food-energy nexus. He previously worked as a political risk analyst covering equatorial Africa’s energy sector, and sustainable development in sub-Saharan Africa. Contact: Cody.Pope@circleofblue.org