Water Safety Activism in Rural Red States Impedes Fossil Energy Development

Opposition to a big pipeline in Kentucky is a case in point.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

BEREA, KY — President-elect Donald J. Trump’s aggressive and unorthodox election campaign included a pledge to dismantle impediments to the speedy development of America’s reserves of fossil fuels. In pursuit of that goal, Trump this week named Scott Pruitt, the Oklahoma attorney general and prominent supporter of his state’s oil and gas companies, to be administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Trump’s devotion to oil, gas, and coal, though, does not necessarily mean the start of an unfettered era of carbon-fueled growth and pollution. Nor are the negative projections expressed by his critics — that Trump could succeed — especially accurate. Numerous social and economic obstacles impede his ambitions. Here in rural central Kentucky, a pro-Trump hub in one of America’s reddest states, a plan by Houston-based Kinder Morgan to switch the type of fuels flowing through an old and big north-south natural gas pipeline and reverse the direction of its flow helps to explain why.

During the past two years, as one of the world’s largest pipeline developers pursued a proposal to repurpose a 72-year-old natural gas pipeline to transport natural gas liquids, Republican residents joined Democrats at the frontlines to block the $US 412 million, 964-mile-long project. The safety of water supplies and preventing risks from possible explosions serve as central principles of the opposition.

“Kinder Morgan sent three people here last year to talk to some of our folks,” said Jim Porter, an economist who retired in neighboring Boyle County and is active in the anti-pipeline campaign there. “One of the statements they made was how surprised they were by the resistance to their project. They kind of expected that kind of opposition in California. But certainly not in Kentucky. It was like they thought it was going to be easy to roll over us hillbillies.”

Melissa Ruiz, Kinder Morgan’s corporate communications manager, had this response to emailed questions from Circle of Blue: “We don’t have much to say on this project other than what we have on our website.”

Kentucky Opposition Part of National Trend

The various struggles to block energy development — and there are dozens across the country — encompass tens of thousands of residents and many elected local and state officials who supported the president-elect. In many cases the protests are assisted by state, regional, and national environmental advocacy organizations. Driven by convictions about water quality, public safety, and property rights, the rural opponents to big fossil energy installations are slowing development and are likely to defy any effort to quell them by the Trump administration.

Kinder Morgan’s 72-year-old natural gas pipeline crosses the Dix River in central Kentucky. Because gas liquids are heavier, the pipeline needs to be rerouted to cross beneath the river, which supplies a reservoir that provides drinking water for three counties. Photo for Circle of Blue/Jim Porter

“Yes, we in the interstate natural gas transmission industry are seeing public protests of our projects,” said Cathy Landry, vice president of communications for the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, a trade group, in an email message to Circle of Blue. “Pipelines have always faced opposition. But historically, that opposition was from local stakeholders – landowners, local communities, etc. – with legitimate concerns about the pipeline routing or questions about its operation.

“What we’ve faced more recently is opposition from those that don’t have a close tie to the pipelines. Typically those are environmental groups that are concerned about upstream practices, like hydraulic fracturing, or fossil fuels in general, that are targeting the pipeline because they are unable to stop the upstream practices.”

Simona Perry, vice president of the Pipeline Safety Coalition, a safety education organization that specializes in emergency preparedness and recovery, told Circle of Blue that local citizens, aware of the risks of leaks and explosions, drive most of the opposition to pipeline projects. “In addition to environmental concerns, other organizations and local citizens are concerned about the siting of pipelines near schools, hospitals, places of worship, and community centers as well as the capacity of communities to respond to pipeline disasters,” Perry said in an email message. “The majority of rural places in the United States rely on volunteer emergency services whose capacity to respond to complex hazardous materials leaks and explosions may be limited. Our work with local emergency services staff and first responders both before and after pipeline disasters in California, Pennsylvania, and Maryland has shown a disconnect between preparedness and training for other types of disasters and the unique circumstances involved in pipeline disasters that may lead to long-term individual and collective trauma and longer recovery processes.”

Two years ago, responding to a surge in serious incidents, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration issued a pipeline safety notice that warned against converting and reversing the flow in certain types of pipelines. The agency, a unit of the Department of Transportation, called on operators to thoroughly test the structural integrity of their pipelines to understand corrosion, wear, and increases in pressure that could lead to failures.

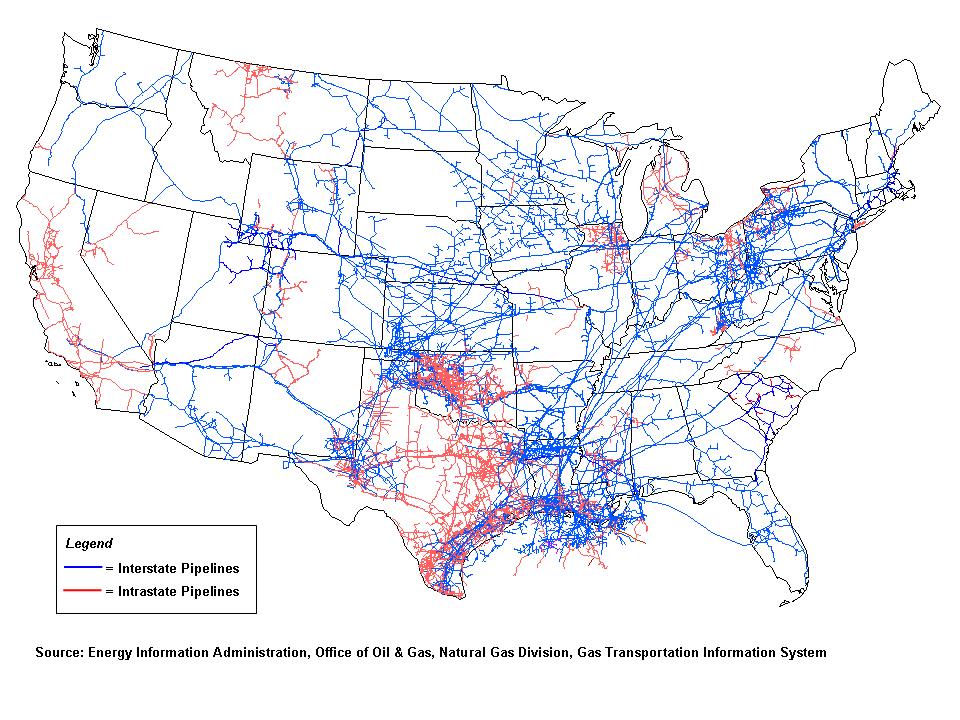

The federal guidance came as America’s natural gas liquids pipeline network expands. Production of ethane, propane, and butane – the natural gas liquids used as fuel and feed stock for plastics – has doubled since 2009, according to the Energy Department. Texas is now being challenged by the deep shale wells of eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and West Virginia as the highest natural gas production region in the United States. Royal Dutch Shell is building a $US 6 billion gas liquids production plant west of Pittsburgh. The domestic and export markets for natural gas liquids is strong and so is the demand for transport.

Long gone, though, is the time when energy companies could swoop into lightly populated regions to build big energy infrastructure projects. More people live in the places close to the unconventional oil and gas drilling fields in the rural West and East. Their daily commutes, backyards, and favorite wild places are disrupted by the transport infrastructure needed to bring fuel to market. Because pipelines cross numerous streams and rivers, and occasionally rupture and explode, pipeline proposals regularly encounter powerful civic resistance.

A Red State Revolt

Kentucky has joined Nebraska, North Dakota, and Georgia as centers of red state opposition. Two years ago a new natural gas liquids pipeline that another company wanted to build in western Kentucky was stopped cold by landowners and state courts. The resistance campaign now waged in central Kentucky, like the previous struggle, features battle-tested lawyers, campaigners, communications specialists, and local government officials of both parties that have drawn lines in the sand to stop the project.

In rural central Kentucky a plan by Houston-based Kinder Morgan to reverse directions and switch fuels flowing through an old and very big north-south natural gas pipeline is stirring opposition. Photo for Circle of Blue/Jim Porter

“The whole idea is extraordinarily ridiculous,” said Craig Williams, a project director of the Kentucky Environmental Foundation who lives in Berea and is one of the most decorated activists in the country. Ten years ago Williams was awarded the Goldman Prize, the top public interest award in global grassroots environmentalism, for his work to halt incineration of the stores of nerve gas held at the Blue Grass Army Depot, 15 miles north of here. “You take a 72-year-old pipeline that moved natural gas from the south to north. Now they want to send north to south a completely different product – gas liquids – through that old pipeline at higher pressures. They want to do this without fully understanding the risks.

“This community is resolved to prevent this project from being completed. Communities and counties through which it passes are exposed to all of the risks and get no benefit from it at all.”

Proposal Encounters Resistance

The battle waged in public meetings, lawyers’ offices, private homes, and local government chambers in Madison and 17 more Kentucky counties crossed by the proposed Utica Marcellus Texas pipeline is a narrative in four dimensions: local, national, regulatory, and legal. Following the defeat in Kentucky of the $US 1.5 billion, 500-mile Bluegrass natural gas liquids pipeline proposed by the Williams Company, Kinder Morgan saw an opening to do the same thing with an existing 964-mile pipeline it owns between the Northeast and Louisiana.

The old pipeline, built in 1944, was a long link in a network that carried natural gas from the Gulf Coast to urban markets in the North. Kinder Morgan asserts that all it needs to reverse the flow from north to south, and fill the line with up to 400,000 barrels of gas liquids daily, is to gain a permit from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to “abandon” the line. That “abandonment” permit request is under review.

Developing a new use for the old line, though, includes investments in new pumping and compression infrastructure and at least one rerouting, said Kinder Morgan. Because liquids are heavier than gas, an overhead crossing on the Dix River in Boyle County needs to be replaced by an underground crossing beneath the river. The river supplies a reservoir that is the drinking water source for three central Kentucky counties.

Pipeline opponents argue that the new crossing, along with the potential risks of the change in the pipeline’s purpose, requires careful government evaluation by states, which oversee liquid fuels pipelines, and perhaps new federal and state air, water, and wetland permits.

The fiscal courts in five Kentucky counties, equivalent to county commissions, have passed resolutions opposing the pipeline. In November, the Danville-Boyle County Chamber of Commerce called for an environmental impact study. In June, Republican State Senator Jimmy Higdon, the Kentucky Senate’s Majority Whip, expressed “serious concerns” in a letter to FERC. Higdon represents Marion County, which is along the pipeline’s 256-mile Kentucky route. “I consider myself a commonsense conservative, and I personally do not know enough about the potential long-term effects of this pipeline conversion, which is why I think we need to take a harder look via a full environmental impact study,” he said.

A plan to repurpose an old natural gas pipeline that crosses the Dix River has stirred influential opposition in Boyle County.

More People Where Fuel Is Developed

Kentucky’s rural pushback, though, should be no surprise. After all, the land and water resources needed for the big new coal mines, power plants, pipelines, and drilling fields that president-elect Trump envisions are not downtown.

The balance of influence has shifted so significantly that bipartisan rural campaigns have forced the cancellation of oil and gas pipeline projects from New England to Georgia, disrupted coal export proposals in the Northwest, and put pressure on oil sands development in Utah. Protests are altering conventional rules of fossil fuel development, transport, and use, and disrupting energy markets in the United States.

In May, for instance, residents of Grant Township, Pennsylvania passed an ordinance that protects citizens from being arrested during protests over a fracking fluids wastewater injection well proposed by a natural gas drilling company. The township, with 700 residents, is in Indiana County northwest of Pittsburgh, where drilling for gas in the Marcellus shale has been extensive and where Trump gained 66 percent of the vote.

Earlier this year, after rural residents and Republican state lawmakers in Georgia objected, Kinder Morgan cancelled its project to build a $US 1 billion pipeline to transport gasoline and diesel fuel to Florida.

In northern Michigan, which voted overwhelming for the president-elect, red and blue voters support closing two 63-year-old oil pipelines that transport 540,000 barrels a day across the Straits of Mackinac and pose a risk of rupture that could ruin fisheries and a strong summer Great Lakes tourist industry.

The $US 3.8 billion Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota has been halted indefinitely since September following months of passionate opposition organized by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. Last year persistent protests, which attracted the support of thousands of farmers and at least one Republican governor across the multi-state Great Plains route of the Keystone XL oil pipeline, prompted President Obama to deny the construction permit.

President-elect Trump said he wants to issue a permit to TransCanada, the Keystone XL builder, to construct the 1,179-mile pipeline, which could cost close to $US 10 billion. Current conditions, though, have changed considerably since the project was initially proposed. Market disruptions largely caused by rising oil production in the U.S. have drastically lowered the price of oil and cut production in the tar sands region of Alberta, Canada, the source of Keystone’s product.

Along with the revival of a powerful multi-state grassroots red-blue opposition campaign in the United States, it would come as no surprise if TransCanada decided not to pursue the project.

———————————————————————————————————————-

UPDATE OCTOBER 17, 2018 — Kinder Morgan today cancelled the project to reverse the flow of its Texas to Ohio natural gas pipeline.

https://insideclimatenews.org/news/18102018/natural-gas-pipeline-kinder-morgan-fracking-utica-marcellus

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider