California Hepatitis Outbreak Has Killed 19 People

State health emergency declared in response to largest U.S. hepatitis A outbreak in more than two decades.

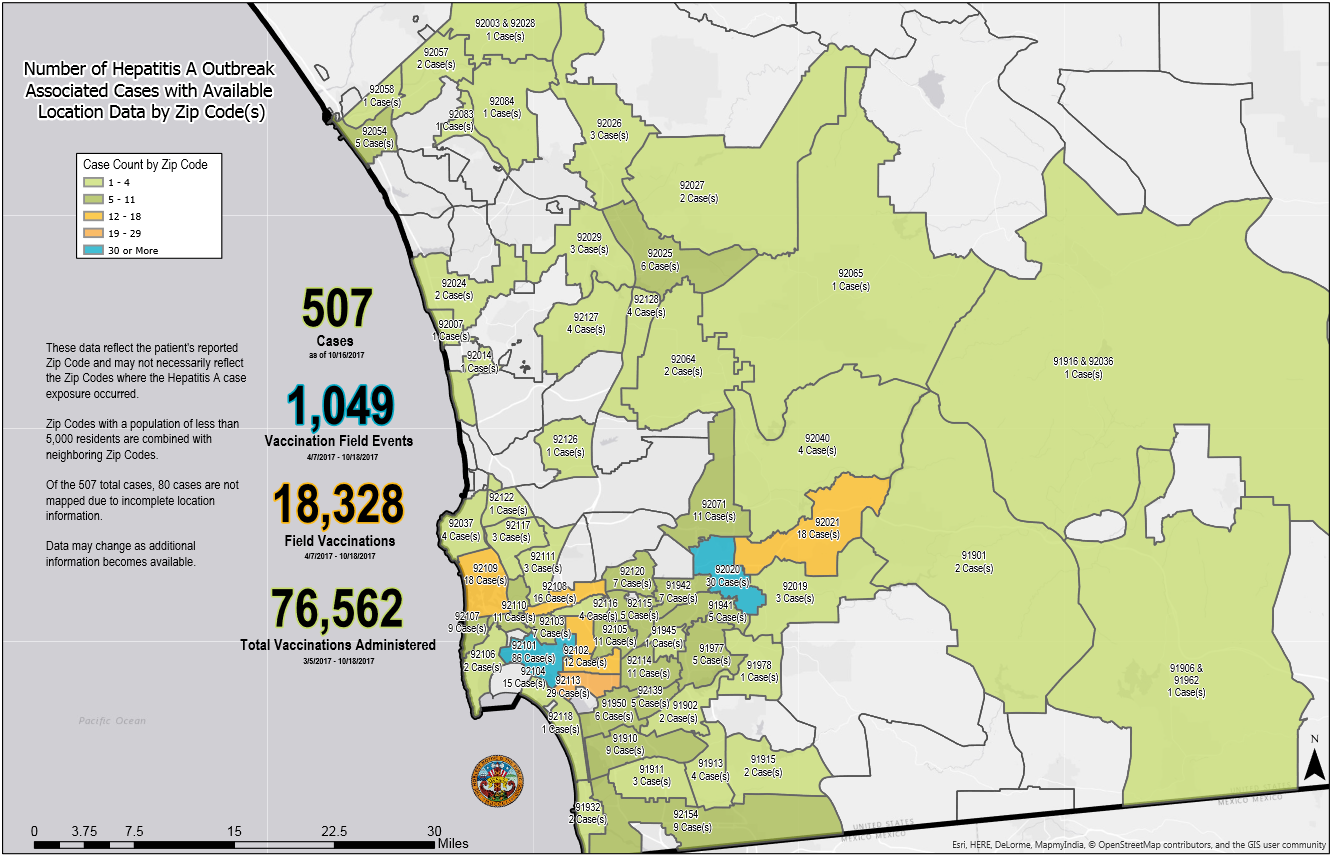

California’s hepatitis A outbreak stems from poor sanitation among San Diego’s homeless population. The map shows the location, by zip code, of reported cases in San Diego County. The highest number are downtown. Click here for a larger version of the map.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

In response to a hepatitis A outbreak that was incubated in unsanitary conditions among the homeless, Gov. Jerry Brown declared a public health emergency last week to contain an epidemic that has killed 19 people this year in California.

The declaration, made on October 13, allows health officials to prioritize the distribution of limited vaccines and to “take all measures necessary” to acquire more.

Spread through contact with fecal waste, hepatitis A is viral infection that damages the liver. Public health officials say that the California epidemic, the largest person-to-person outbreak in the United States since 1996, can be contained in two ways: vaccines and sanitation.

“Sanitation, particularly access to toilet facilities, and careful handwashing after contact with feces and before eating is important for reducing disease transmission,” said Gil Chavez, the California state epidemiologist.

“Clearly one of the risk factors in this outbreak are individuals who happen to be homeless and lack access to regular sanitation,” Chavez added. “Anything that can be done to improve access to sanitary facilities for individuals who are homeless will go a long way in helping to prevent the outbreak.”

Sanitation, particularly access to toilet facilities, and careful handwashing after contact with feces and before eating is important for reducing disease transmission.” — Gil Chavez, California state epidemiologist

San Diego health authorities documented the spread of the disease among the homeless in March. Cases then emerged in April in Santa Cruz, nearly 500 miles to the north. San Diego County, the epicenter of the crisis, declared a public health emergency on September 1, and is washing its sidewalks with bleach. Some two weeks later, on September 19, Los Angeles County, its neighbor to the north, also declared a public health emergency.

Nearly 85 percent of cases — 507 out of 600 — and all 19 deaths occurred in San Diego County.

The homeless and drug users have highest disease rates in the outbreak, Chavez said. At highest risk are those who cannot find an open bathroom. Chavez said that the viral strain causing this outbreak is rarely found in the Americas and is more common in Mediterranean and South Africa. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) does not know how the virus entered San Diego County, but it does think that it was introduced by an infected person and not contaminated food.

CDPH has sent 81,000 doses of vaccine to affected counties. Those vaccines were acquired from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, but Chavez said that the CDC is approaching a limit for the vaccines it can provide. The declaration of a state emergency will help the department coordinate the distribution of vaccines to the people at greatest risk of infection and transmission.

Sanitation Is a Public Good

The outbreak is bringing renewed attention to inadequate bathroom facilities for California’s homeless population. The state has the highest poverty rate in the nation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure, which accounts for housing costs and other living expenses.

Sanitary conditions have been a health concern in San Diego for years. In 2015, a grand jury report criticized the city for slow action. “For more than a decade the city has been advised of the need for more public restroom facilities in the downtown area for the general public, tourists, and the homeless,” the report stated. Businesses and downtown property owners, according to the grand jury report, had objected to additional toilet facilities, fearing that more services would attract more homeless people.

Since September San Diego has added four portable restrooms to the downtown area, bringing the number of sites with public toilets to 23. It also added 60 handwashing stations

San Diego is the center of the current outbreak, but it is not alone in its neglect of toilets for the homeless. A coalition of nonprofits and residents compared toilet access in Skid Row, a 50-block area of downtown Los Angeles with a large homeless population, to United Nations standards for long-term refugee camps.

The Skid Row audit, conducted in the winter of 2017, found that the area was 80 toilets short of meeting the UN standard during nighttime hours. During the day, when shelter residents are emptied onto the streets, the area is 164 toilets short. More importantly, many toilets were frequently out of service or lacked toilet paper or paper towels.

What about the rest of the state? How many do not have easy access to toilets? Laura Feinstein, a researcher at the Pacific Institute, an Oakland-based think tank, has looked at what little data exists. Using two data sets — the American Community Survey and state counts of the number of homeless living on the streets — she estimates that roughly 178,000 people in California do not have easy access to a toilet. These could be people sleeping in a van, on a boat, in a tent, under a bridge, or in a city park.

Access to adequate sanitation is presumably a component of the state’s human right to water law, which was passed in 2012. The law states that every person in California has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.”

Officials in the State Water Resources Control Board told Circle of Blue that, because financial and staff resources are limited, they are prioritizing drinking water access over sanitation. Drinking water advocates also say that sanitation is a blind spot, both in funding and in data collection.

Sanitation “has been the overlooked portion of the human right to water,” Feinstein told Circle of Blue.

Water officials are taking note of the sanitary connections to the hepatitis A outbreak.

“It has influenced us,” Mike Antos, senior watershed manager for the Santa Ana Watershed Project Authority, a southern California water supply collaborative, told Circle of Blue. In June, the authority hosted a symposium on how to serve the homeless population. Antos is planning a second symposium for December and looking at how state grant funds might be used to extend water services to the homeless.

Sanitation for the homeless will still be a timely topic this winter. When asked if the outbreak might last several months to more than a year, Chavez would not impose a timetable. The quicker that people are vaccinated, the quicker the outbreak will be contained and eliminated, he said.

“Our goal is to reach everyone at risk and get them vaccinated,” he remarked.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton