Choke Point: Tamil Nadu

New reporting project describes how drought, storms, and floods are forcing big Indian state to contend with severe water stress.

By Keith Schneider

Circle of Blue

TUTICORIN, INDIA — Among the 75 government ministries that manage and regulate this bewitching and impassioned nation, there is no Ministry of the Future. There should be.

Narendra Modi, the prime minister, has stirred a buying spree following his party’s 2014 electoral victory. The former chief minister of Gujarat, a western Indian state, coaxed domestic and international investors to build new ports, develop new mines, build electric generating stations, purchase military jets and ships, and lure multi-national, high-tech companies to set up back-office operations in the country’ s biggest cities. Modi’s development-at-any-cost model looks a lot like the plans that richer counterparts executed in the previous century: the Marshall Plan that the United States deployed to rebuild Western Europe after World War Two, and the opening of the Chinese economy in the 1980s under Deng Xiaoping.

The 21st century though has produced new circumstances that are impeding Modi’s development goals: dire ecological stress, disarray in economic markets, and swelling civic resistance. An Indian Ministry of the Future would help this nation of 1.3 billion people understand that vastly altered patterns of rainfall and water use are literally drying up the nation, causing huge financial losses and leading to deepening social conflict. Such a ministry, were it so empowered, might also convince India’s leadership to replace its obsolete and dangerous development strategy with a much more pragmatic approach that elevates ecological values, especially the conservation of water, as essential principles of progress.

Drought in Tamil Nadu has ruined rice crops, even those that look green. Farmers that irrigate in the Cauvery Delta only from surface water supplies sustained total crop failures this year. Photograph @ Dhruv Malhotra/Circleofblue.org

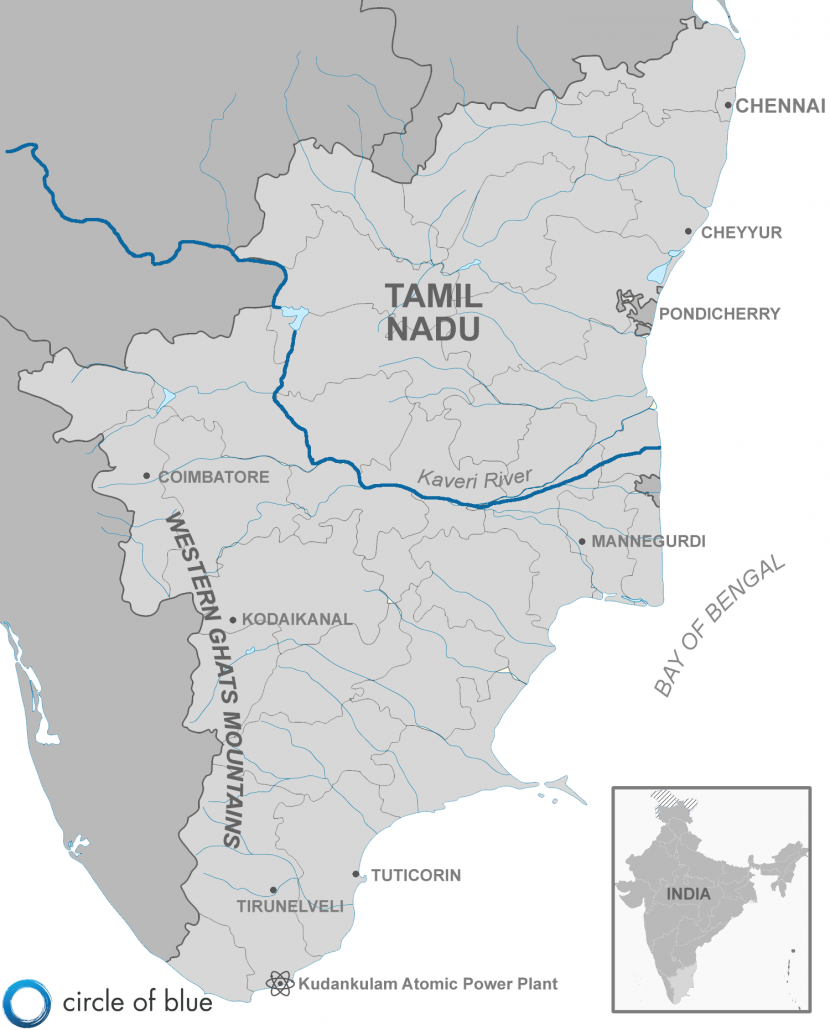

The Ministry of the Future could easily start its work here in Tamil Nadu, a state that sits at the southern tip of India’s geographic triangle.

Tamil Nadu is renowned in India for its thriving and orderly cities, superior medical care, and fine universities. Chennai, its capital, is the country’s fourth largest metropolitan area. Defined by the Bay of Bengal on the east and south, tall mountains and forests to the west, and flat coastal plains, Tamil Nadu also is pitched on the frontlines of the powerful forces of climate, water scarcity, and fast population growth that are beginning to bludgeon the Earth’s densely populated coastal regions.

This month Circle of Blue, in collaboration with the Wilson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, is in Tamil Nadu. We are here to take a close look at how a big Indian state of 78 million residents, and the country’s second largest economy, is responding to the powerful disruptions in water supply, energy, and farm and business markets that have overtaken much of India and the world. With the help of Care Earth Trust, a Chennai-based environmental science group, and four Indian journalists — environmental reporters S. Gopikrishna Warrier and Sibi Arasu, and photographers Dhruv Malhotra and Amirtharaj Stephen — we are producing Choke Point: Tamil Nadu. It is the latest chapter in our Global Choke Point project, which since 2007 has closely examined the competition for water, energy, and food on a planet challenged by the rapidly changing climate.

Tamil Nadu, the big southeast Indian state along the Bay of Bengal is gripped by the deepest drought since 1876. Rivers are dry. Water supplies for farmers are scarce, killing harvests. The drought’s effects are a facet of big public demonstrations that lasted for over a week in late January all over the state. Here, the Cauvery River has no water for irrigation. Photograph @ Dhruv Malhotra/Circleofblue.org

A Bay of Bengal Laboratory of Eco-Stress

Tamil Nadu’s treacherous position along a dynamic coastline of warm, storm-fueling water, is exacting a huge economic and human toll. Erratic rainfall and sharp growth in population and businesses has drained groundwater. Industrial and human wastes contaminate surface water. A sizable share of the drinking water in the capital of Chennai is transported from rural wells and served from tanker trucks and plastic bottles.

A deep drought now grips the state, killing harvests and producing drinking water shortages. In Karnataka, a neighboring state, riots erupted in September over a court order to share water from the Cauvery River. A hospital in Coimbatore cancelled surgeries because the water reserves stored in big plastic tanks ran dry. The drought generates such stress on farmers in this state’s Cauvery Delta region, one of India’s great grain bowls, that 17 farmers have committed suicide in the last several months. Over 100 more have died of heart attacks. The region has never experienced such mortality from depleted harvests, a 59-year-old cardiologist told us.

November and December are especially tough months for Tamil Nadu. Two months ago, in December 2016, a cyclone blasted the northern reaches of the state, piling streets with downed trees and halting electricity and water distribution for a week in Chennai and nearby communities. A year before, heavy rains caused a flood that overflowed sewage treatment plants and drowned almost all of Chennai in fetid waters that killed 18 people and brought the city to a near standstill for a month. More than 400 others died from flooding across the state, according to the state’s chief minister. The offices and warehouses of EBay, Amazon, and other prominent tech companies housed in new buildings in Chennai’s IT corridor were shut and lost millions of dollars.

In December 2004, without warning, huge waves rose up from a Pacific tsunami and crashed against Tamil Nadu’s 1,072-kilometer coastline (669 mlies). The sea tore through fishing villages, demolishing homes and businesses. More than 6,000 people drowned.

Seven years later, in November 2011, a cyclone wrecked the $US 2 billion Nagarjuna oil refinery, which was under construction along the coast in Cuddalore District. Later, a big new coal-fired power plant just 14 kilometers (8 miles) away also got into trouble. A citizen lawsuit questioned the plant’s effects on coastal fisheries and water supplies, and the legitimacy of studies and permits used by the company building the $1.6 billion generating station. A decision in 2014 by the National Green Tribunal, a high court that decides environmental cases, halted construction of three new electrical generating turbines at the plant. Together, the refinery and power plant form one of the most costly clusters of stranded fossil fuel assets in the world.

Tamil Nadu, in sum, joins Venezuela, Brazil, Nepal, almost all of Africa, and northern China as a region beleaguered by acute ecological change that also is producing billions of dollars in losses, draining economic performance, and causing social unrest.

A farmer from Mannargudi, in the Cauvery Delta region of Tamil Nadu, stores scarce water in stainless steel pots and a cistern at his home. The worst drought in 140 years is battering the southeast Bay of Bengal state. Photograph @ Dhruv Malhotra/Circleofblue.org

A Civil Reckoning and Awakening

Government officials are not ignoring Tamil Nadu’s situation. Nor have the state’s citizens and influential public interest organizations. A powerful civic awakening is unfolding across Tamil Nadu that is driven in large part by water stress. Various campaigns, organized on Facebook and Whatsapp, are challenging polluters, and bringing lawsuits that disrupt operations of soft drink bottlers and other water consuming industries. Tamil residents say water shortages are impeding their constitutional “right to life.” Access to adequate supplies of clean water is seen as an essential facet of that right.

Chennai has turned to desalination plants to convert the salty waters of the Bay of Bengal into drinking water to meet some of the city’s rising demand for water. The city also is evaluating its land use planning to prevent more of its marshes and ponds from being paved over for new buildings.

Prime Minister Modi, in a signal shift from coal, is positioning this state and more than a dozen others to develop cleaner, less water intensive energy industries. The idea, Modi asserts, is to help cool the planet, stabilize water reserves, and heat up India’s economy. Tamil Nadu is host to the world’s largest photovoltaic generating station, and enormous wind farms. The Central Government backed away from building a 4,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant along the coast in Cheyyur that would have forced the relocation of three coastal villages and thousands of fishing and farm families who have sustained an ecologically-balanced way of life for hundreds of years. Shelving the Cheyyur coal plant and encouraging a powerful move to wind and solar energy signals a pivot on much cleaner sources of electrical generation that is internationally significant.

Coal-fired power plants still dominate Tamil Nadu’s electrical supply grid. Here a sea water-cooled power plant, framed by salt-making evaporation ponds, along the Bay of Bengal in Tuticorin. Photograph @ Dhruv Malhotra/Circleofblue.org

Introducing Choke Point: Tamil Nadu

Choke Point: Tamil Nadu comes amid the rapid evolution in the narrative of economic and ecological confrontation over resources that Circle of Blue and our partners at the Wilson Center developed over the last ten years. In Divining Destiny, we discovered how water scarcity in Mexico influenced immigration patterns to the United States. In The Biggest Dry, we found that a deep drought in Australia’s Murray-Darling basin damaged rice and wheat crops that played a role in the higher food prices that touched off the 2010 Arab Spring. In Choke Point: China, Circle of Blue documented a momentous shortfall in water supplies in the Yellow River Basin that would impede China’s economic development. Our reporting discovered that water supplies were not nearly sufficient in the dry provinces of the basin to construct new cities, harvest a fifth of China’s grain crop, mine and wash more than 2 billion metric tons of coal, and build dozens of water-consuming coal-fired power plants. Those findings and several more elevated China’s severe energy-water choke point to national attention, prompted China to launch new scientific studies, and played a big role in informing the negotiations that led to the 2014 U.S.-China agreement to limit carbon emissions. Two of the pact’s six provisions focused on energy and water.

By the time we launched the Choke Point: India project in 2012, and then moved to frontline reporting in the Arabian Gulf, Mongolia, Panama, Peru, South Africa, and across the United States we documented converging economic and ecological trends, all of them centered on water, that are battering the world.

In 2016, the Global Choke Point project also led to reporting on how citizens around the world are exerting pressure on big international banks. The various campaigns are intent on impeding the construction of mammoth power plants, dams, mines, pipelines, and industrial farms that stress water supplies. The series of articles on finance and water stress has helped to elevate the role that big banks play in encouraging industrial infrastructure projects that lose money, ruin water supplies, and harm rural communities around the world.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor Keith Schneider interviews a farmer south of Chennai about drought, water supply, and using groundwater for irrigation. Photograph @ Dhruv Malhotra/Circleofblue.org

Big Research Agenda

The Choke Point: Tamil Nadu research objectives are ambitious. They include a report on how water stress affects recruitment and development of Chennai’s IT sector, the city’s fastest growing industry. Another report focuses on how Chennai’s operating system is becoming more resilient to droughts and floods. A third report describes the strife over the Cauvery River, where development and drought have produced a two-state conflict over water supplies that is one of the fiercest in the world. Additional reports focus on India’s new shift away from coal, renewable energy, Chennai’s big water bottling sector, and the state’s resistance to Coke and Pepsi bottling scarce water supplies for soft drinks.

Like our other Global Choke Point projects, Choke Point: Tamil Nadu considers carefully trends in water demand and supply, economic performance, and human progress in a big Indian state. The project focuses on two principal objectives. The first is to thoroughly explore how Tamil Nadu’s economic industrialization policies, designed during a less crowded, more ecologically stable century, are producing increasingly dire consequences, especially for the state’s uncertain freshwater reserves. The second is to report on how Tamil Nadu’s political leadership and the Modi administration recognize that fresh and courageous leaps in economic and environmental logic are needed to assure adequate water supplies and civic stability.

Chapters of the report will be posted by Circle of Blue and the Wilson Center starting in March. Next summer Circle of Blue and the Wilson Center will tour Tamil Nadu and India to present the project’s findings in a series of public events.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider