Risks Grow for Deadliest U.S. Drinking Water Hazard

Reported cases of Legionnaires’ disease are surging upwards.

Legionella bacteria grow in plumbing systems where warm water sits for long periods of time in pipes. The bacteria can be scattered in the air by cooling towers and fountains. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

In the weeks after Labor Day, 15 people who live in or visited Anaheim, California fell ill with a common set of symptoms: fever, chills, and coughing. Thirteen of the 15, all between the ages of 52 and 94, required treatment at a hospital and were diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease, a pneumonia-like illness that attacks the lungs. Two people died.

An ongoing epidemiological investigation by the Orange County Health Care Agency found that, in September, 11 of the 15 individuals visited Disneyland Park, Anaheim’s legendary megaresort. In conversations with Disney staff, county health investigators and their state and federal partners learned that water in two cooling towers at the resort had tested positive for Legionella, the bacteria that cause the disease. Cooling towers, a part of large-scale heating and air conditioning units, are a breeding ground for Legionella if not disinfected and maintained.

Medical and public health authorities have known the causes and serious consequences of Legionnaires’ disease since 1976 when an outbreak stemming from an American Legion convention in Philadelphia sickened 221 men and killed 34 of them, thus giving the disease its name.

The Anaheim cluster is the latest U.S. outbreak of the respiratory disease, the nation’s deadliest waterborne illness. Spread by inhaling contaminated mist or steam, the Legionella bacteria routinely sicken thousands of U.S. residents each year and kill several hundred.

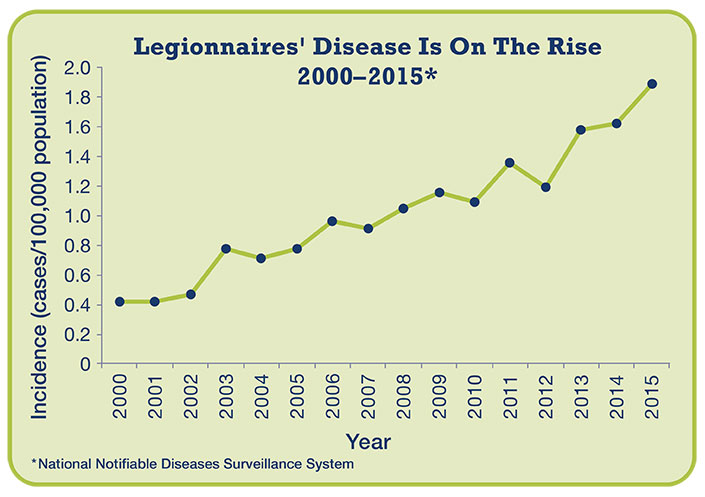

Worse, the number of reported cases nationally is rapidly growing. The CDC found that cases more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2015. Whether the increase is due to more diligent reporting by state and local health agencies, better diagnostic tests, degraded water pipes, an aging population, careless building maintenance, or to other factors is a matter of debate.

What is clear from conversations with engineers, researchers, and public health officials is that the disease and its transmission is poorly understood and, until recently, largely neglected. Though deadly, the disease had not been a high priority for building owners or managers. Guidance for testing and maintenance of building water systems is haphazardly applied, while regulations are antiquated, ineffective, or nonexistent.

New federal regulations for Medicare facilities that went into effect in June aim, in part, to change that. “We believe that increased knowledge in how to recognize and treat the disease can help bend the [infection] curve downwards,” Chris Edens, a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologist, told Circle of Blue.

A Unique Disease

Legionella bacteria, which exist in rivers and lakes, thrive in warm, stagnant water found in building plumbing systems, decorative fountains, hot water tanks, hot tubs, showerheads, and faucets. Legionnaires’ disease kills about one in 10 people who are infected, but it is not contagious.

Outbreak investigations read like movie scripts.

From June to November 2005, some 18 Legionnaires’ disease cases, all in people over the age of 50, were reported in Rapid City, South Dakota. An investigation by the South Dakota Department of Health and the CDC connected the illnesses to a decorative fountain in the lobby of Casa del Rey, a Mexican restaurant. The one-foot-high water spout in the center of the bowl, its flow not much stronger than a drinking fountain, had dispersed contaminated droplets into the air.

Outbreaks linked to fountains are rare; most illness clusters happen in hospitals and health care facilities or are a result of cooling towers. That was the case in New York City in the summer of 2015, when 138 people fell ill and 16 people died from contaminated water dispersed from the rooftop cooling tower at the Opera House Hotel, in the South Bronx. Bacteria were scattered widely by the wind; infections were reported by people living more than a half mile away. The outbreak led to a city ordinance and state regulation of cooling towers as well as water systems in hospitals and nursing homes. The rules require registration of cooling towers, periodic inspections, and regular water testing.

Two U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assessments on disease outbreaks found that Legionnaires’ disease caused at least 30 deaths in 2013 and 2014 and more than 200 hospitalizations, and was responsible for three out of five water-related disease outbreaks.

The tests at Disneyland’s cooling towers were done in early October, some weeks after park-goers were exposed to the bacteria but before health officials were aware of the outbreak.

The number of reported Legionnaires’ disease cases has more than quadrupled since 2000. Graphic via the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Disney shut down the cooling towers pending further testing. Jessica Good, spokeswoman at the Orange County Health Care Agency, told Circle of Blue via email that the agency is still investigating the outbreak. The cluster of cases from people who visited Disneyland “indicates a pattern but does not identify that specific location as the common source of infection for all cases,” Good wrote.

The CDC believes that there is no additional risk of infection from this outbreak because no new cases have been identified and symptoms develop up to two weeks after exposure.

Where the Built and Natural Environment Collide

As CDC epidemiologist Chris Edens says, preventing outbreaks and reducing the incidence of the disease will require significant improvements in knowledge and practices. One order of business is for health officials and building managers to understand the risk factors.

Some researchers, knowing that the old and sick are most vulnerable, reckon that changes in U.S. demographics contribute to the rise in cases. All Legionella-linked outbreak deaths reported in 2013 and 2014 occurred in hospitals, healthcare facilities, or nursing homes, and people over age 50 have the highest risk of infection.

Others point to aging and corroded drinking water pipes, which can incubate the bacteria. That happened in Flint, Michigan, where six public officials face involuntary manslaughter charges stemming from an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in 2014 and 2015, which killed 12 people. The outbreak is linked to the corrosive water that caused the city’s lead crisis.

Bacteria can also infiltrate water systems when water mains break. Edens said that Legionnaires’ incidences spike after water pipe ruptures.

Once in the water system, the last line of defense is the building plumbing. Engineers look at hospitals, apartment towers, and nursing centers and note deficiencies in design, operations, and maintenance. Legionella is “an engineering system pathogen,” so it has to be confronted where it grows: by more attentive oversight of complex building plumbing, argues Tim Keane, an engineer who runs Legionella Risk Management, a Pennsylvania-based consultancy.

Keane told Circle of Blue that the architecture and plumbing of hospitals increases the risk of Legionella growth. Facility construction guidelines recommend that every room has a shower, even if they are rarely used. Water that sits in the plumbing is a petri dish for the bacteria.

“Hospital design is horrible,” he said. “It doesn’t do anything to acknowledge Legionella.”

Operational decisions within buildings also play a role. Energy and water conservation, noble ideas on their own, can produce ideal conditions for bacterial growth. Less water flowing through pipes results in stagnant water, while turning down water heaters to save energy brings water temperatures within the comfort zone for the Legionella bacteria, which die when water is above 140 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We’re trying to find the right balance between public health, being green, and conserving,” Aaron Prussin, a research scientist at Virginia Tech who studies Legionella, told Circle of Blue. Prussin said that the rise in Legionnaires’ cases is complex convergence of factors and it is likely that all these influences have aided the disease’s emergence.

Lack of Concern and Deficient Regulations

Public health authorities and plumbing experts are aware of the rising number of cases, but are split on how best to respond. Two camps, neither mutually exclusive in its recommendations, have emerged. One focuses on better management of water in the pipes, heaters, cooling towers, and boilers within buildings, the so-called “premise plumbing.”

National engineering organizations have developed standards in the last two years for managing water within buildings. ASHRAE, a professional organization for building design, released a standard in 2015 for managing the risk of Legionella contamination in premise plumbing. Earlier this year, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, ordered health care facilities that accept Medicare to adopt policies to reduce the risk of Legionella. The agency recommends the ASHRAE standard, now considered the model program.

The other camp argues that the burden should not solely be placed at the end of the pipe. Instead, groups such as the Alliance to Prevent Legionnaires’ Disease, an organization of health professionals, engineers, and manufacturers, assert that more attention ought to be paid on boosting immunity within the entire water utility system, from the treatment plant through the distribution mains to the faucets and water heaters inside hospitals and nursing homes.

Daryn Cline, the alliance’s director of science and technology, said that water utilities may need to boost chlorine, which kills bacteria but degrades over time, in parts of the distribution system. “We have to look at the source water, too,” Cline told Circle of Blue.

Chlorine would help in buildings too, but federal regulations prevent managers from treating water with the disinfectant. Large complexes, such as hospitals, are frequently authorized under the Safe Drinking Water Act to run their own treatment systems. But most large buildings draw water from the distribution grid, as do homes and businesses. Adding chlorine or otherwise tinkering with the water chemistry would reclassify a building as a water treatment operator and result in additional layers of oversight and reporting. Few building owners desire that. Keane and others said that the EPA ought to review this rule.

The CDC, which provides technical assistance to public health departments and building owners, recently asked how Legionella could be contained within buildings.

Comments submitted to the CDC suggested three main barriers. Some building owners lack financial resources to develop a management plan, hire maintenance staff, organize data, or conduct regular water testing. Other building owners simply do not know enough about the risks of Legionella or how to operate their plumbing systems to minimize risk.

A number of commenters said that existing guidelines are sufficient but few improvements would be made until federal regulations changed.

“Federal and state governments need to completely overhaul, and bring up to date, drinking water regulations and change them to require minimum filtration rates as well as minimum sanitizing standards to prevent legionella and other waterborne pathogens from thriving in municipal water systems,” wrote John Letson, vice president of plant operations for Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in a comment to the CDC.

Matt Freije, founder of HC Info, a building water management consultancy, says that he sees few building managers willing to make improvements voluntarily. Most facilities, he told the CDC, “simply will not implement prevention until it’s required by a law or to maintain liability insurance.”

This story has been updated since first publication with the latest numbers on the Orange County outbreak.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton