https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A7610-2500.jpg

1600

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2018-07-03 15:03:082019-06-24 15:35:12Chennai’s Security Tied to Cleaning Up Its Water

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A7610-2500.jpg

1600

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2018-07-03 15:03:082019-06-24 15:35:12Chennai’s Security Tied to Cleaning Up Its WaterA Torrent of Water and Concrete Imperil Chennai’s IT Boom

The third in a series of reports by Circle of Blue and the Wilson Center on the global implications of water, energy, and food challenges in the south India state of Tamil Nadu.

By Sibi Arasu

Circle of Blue – April 25, 2017

CHENNAI, India – Almost a decade ago, when the first of Chennai’s bleach-white IT office buildings replaced coconut groves along the Bay of Bengal south of the city center, leaders hailed the potential for a new wave of clean jobs. Nine years later, it is clear that planners did not fully anticipate the consequences.

Information technology proved so popular in Chennai that it is now India’s second largest IT center behind Bengaluru. But in bringing down protective coconut palms and constructing the dense strip of offices and contemporary residences atop water-absorbing coastal wetlands, planners put the city’s fastest growing business sector at the mercy of Tamil Nadu’s suddenly dangerous meteorology.

In the last 18 months, the IT corridor has been bullied by fierce flooding, a dangerous cyclone, and severe drought. New home buyers are starting to settle in other neighborhoods in north and west Chennai. Nervous IT office managers are weighing relocation.

“Ecological distress has always been a factor but it’s surely moved up the value chain because of the last few years,” said Preetam Mehra, the head of Chennai operations for the American commercial real estate services firm, CBRE. “Chennai didn’t have a history of any major ecological events and hence that was not on top of people’s minds. Now, everyone is more diligent about where they invest, taking further precautions about how and when they want to invest.”

Seasons of Trouble

Chennai’s location along a dynamic coastline of warm, storm-fueling water has periodically put it in the path of extreme weather throughout its 400-year history. But the now 10-million strong metropolitan area has never been hit so hard as it has over the last two years.

In November and December 2015, Chennai recorded never-before-seen amounts of rainfall, leading to flooding and complete inundation of low-lying areas inside the city as well as in suburban areas. The city received more than 1,700 millimeters (67 inches) of rain in a span of three weeks; 272 mm (11 inches) of rain fell in 12 hours on December 1. Typically, the entire month of December receives 191 mm (7.5 inches).

While even the most robust city infrastructure would face inundation under such conditions, Chennai’s inadequate water storage and drainage infrastructure contributed to the flooding, which killed 470 people in the metropolitan region, according to state government figures. At one point, the Chembarambakkam reservoir, one of Chennai’s major water reservoirs, threatened to burst. City engineers responded by releasing a torrent of water into the Adyar River. All of the settlements along the 42-kilometer (26 miles) stretch of the river that runs through the heart of the city were completely inundated. The raging river rushed into already flooded lakes and ponds and drowned the IT corridor. Water rose to the second floor of some buildings. Chennai and its high tech business district were out of commission for two weeks.

Office managers had barely finished repainting and replacing water-logged furniture when Cyclone Vardah stormed in from the Bay of Bengal in early December 2016. The cyclone uprooted Chennai’s urban forest, downing more than 100,000 of the city’s 450,000 trees; power lines snapped across the city; and an undersea cable that supported the corridor’s online networks was severed. Again, it took weeks for normalcy to return.

Cyclone Vardah struck as Chennai was also in the midst of its worst drought in 140 years. Water scarcity has disrupted drinking supplies, contributed to rising food prices, and put India’s fourth largest metro area on notice that a new era of acute ecological disruption has dawned.

Not Business as Usual

According to estimates, the economic tolls of the flood and cyclone were pegged respectively at $3 billion and $1 billion citywide. Chennai’s IT industry accounted for some $60-million worth of losses from the floods. Industry losses from the cyclone have not yet been calculated, though authorities project they will be consistent with the value of the flood damage because electricity and internet access were hit so hard.

“Luckily we make it a point not to have any offices in the ground or any of the lower floors, so that saved us from a lot of damage,” said Narasimha NK, director of finance at Ajuba Net, a leading business processes outsourcing firm. “The bigger problem for us was that the net connectivity was affected. We are heavily dependent on voice links. That was a big setback. The local government needs to concentrate on drainage, roads, and better public infrastructure, especially in the IT corridor. Having said that, extreme weather is a reality in many of the big cities across the world now.”

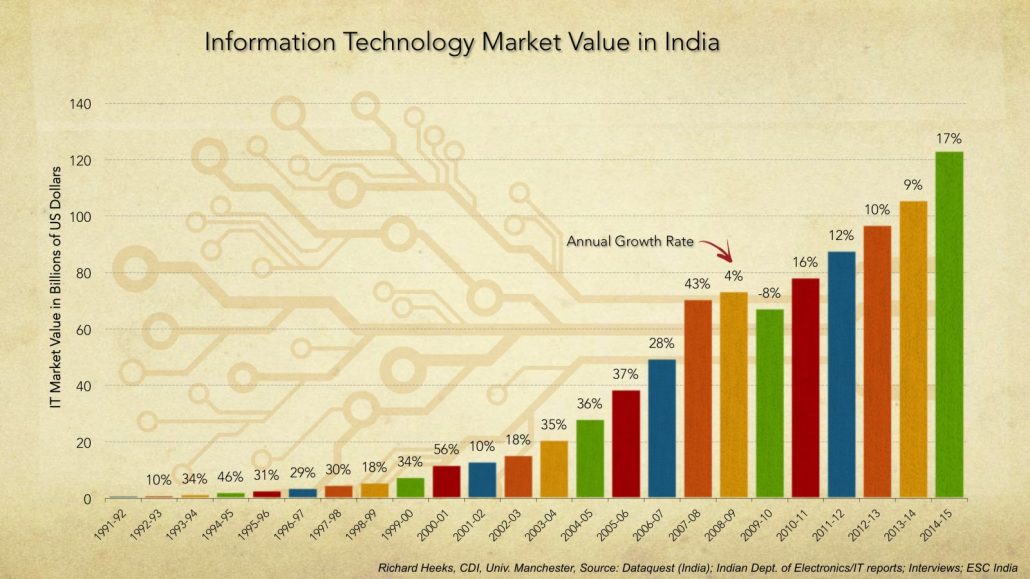

Information technology is a $150 billion-a-year industry in India. Chennai’s IT corridor hosts offices for some of the most recognizable multinational brands in software, outsourcing, computer design, engineering, and telecommunications, including Accenture, Amazon, eBay, Microsoft, IBM, Ford, TCS, Infosys, and Verizon. The city offers much to recommend for employers including a well-educated and skilled pool of workers, clean beaches, warm weather, and a sunny cultural disposition. Market research firms reported in 2016 that Chennai’s IT sector accounted for 15 percent of the $110 billion Indian software export market.

Formally launched in 2008, the IT corridor project was intended to amplify those recruiting assets. More than 200,000 people are now employed in 1.3 million square feet of office space. The corridor’s construction was divided into two phases. The first involved building roads and related infrastructure for offices and residences along a 20-kilometer (12 miles) boulevard. The second phase, not yet finished, extends the development 26 kilometers (16 miles) further.

Whether it gets that far is now in doubt. While the corridor’s linear design runs as straight as an arrow, its land use and infrastructure planning are scattershot. Local panchayat (rural development) bodies, mostly falling under neighboring Kanchipuram and Thiruvallur districts, were allowed to make decisions on land sales and construction. Development goals supplanted all other priorities, especially safeguarding the area’s assortment of lakes and wetlands. Big buildings and expanses of pavement replaced water-absorbing marshes. In particular, new residential construction and IT office space have steadily encroached on the 230-square-kilometer (90 square miles) Pallikaranai freshwater marsh over the last decade.

“People need to understand that lakes, ponds, and other water bodies have great enviro-economic value to them,” said Arun Krishnamoorthy of the Environmental Foundation of India, which specialises in cleaning up and restoring water bodies. The IT corridor has some of the largest water bodies in and around Chennai which are now greatly encroached upon. “For me, the IT corridor is a model of how not to develop,” he said. “There’s no long-term vision for the area and we are now paying the price for this.”

Informal Water Networks

Local governing boards also left it up to developers whether to build a unified water transport and waste disposal system. Most chose to forget about it. Water is instead supplied to office buildings and residential communities by over 850 tanker trucks a day, each containing 12,000 liters (3,200 gallons).

To deal with sewage, buildings use individual septic systems. A few IT offices have taken a zero waste policy where all wastewater is recycled on site. Most, however, rely on sewage tankers to haul the wastewater to a nearby treatment plant.

The lack of basic necessities is proving to be a new deterrent for business in the aftermath of the floods and the advent of the drought.

The precariousness of the informal water transport network was first exposed in October 2014 when a strike by truck drivers almost brought business along the corridor to a complete halt. While the tanker owners called off the strike within two days, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry estimated that another day of strike would have led to $16 million in daily losses.

“I have always thought of Chennai as a city of corridors,” said A. Srivathsan, a professor at the Center for Environment Planning and Technology in Ahmedabad. “The city planners never thought of building a silicon city or an enclave. They wanted to stretch development to a larger region. But they didn’t think of developing integrated transport nor facilitating for basic infrastructure and services.”

“The promise was that once big-ticket investments came in, it would create linkages and generate jobs,” said Vijaya Bhaskar, a professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies. “But basic public services are, for some reason, not considered important or critical, and that has been the biggest problem with the IT corridor.”

“The promise that the IT corridor was built with is only halfway there,” Bhaskar said. “But in many aspects it is already crumbling – the corridor as well as the promise. These companies usually tend to carry on until local resources are exhausted and then move on elsewhere. In Chennai, if these issues are not addressed proactively, the chance of resources getting exhausted, as well as IT majors shifting out soon, taking their business with them, is a serious possibility.”

Dealing With Disaster

The triple whammy of flood, cyclone, and drought revealed how vulnerable the IT corridor is to disruption. Companies are now busy writing contingency plans for environmental disasters. “Ecology is a serious economic factor in people’s minds,” said Preetam Mehra of CBRE.

Just how serious is a matter of dispute among IT office executives and city authorities. Many executives assert that Chennai’s business climate is stable and the city’s ecological torment is consistent with conditions in other competitor metro areas. They also said in interviews that the extreme weather events of the last two years are aberrations.

“As of now, it’s not a big issue,” said Narasimha NK of Ajuba Net. “Despite all the problems, Chennai, especially the IT corridor, is a better place to do business than other locations. We believe the risk of a flood sort of situation repeating again is not very high and hope the worst is behind us.”

“The lack of infrastructure is a relative factor,” said Aubrey Daniels of the American Chamber of Commerce in India. “The fact is that Chennai is a cheaper city to work compared to other cities. It also has a large, well-educated talent pool available, which is not the case elsewhere. I doubt there’s a serious risk of losing business. The ability to bounce back from catastrophe is high here. In case of disasters, if there is no power, companies are happy to run generators because they know that the city authorities will step up and restore electricity as soon as they can.”

Other authorities insist that the risk of serious environmental disruption is grave and likely to grow worse without evasive action. “It is a big risk already,” said Arun Krishnamoorthy. “Many IT firms get damaged massively every time there’s an extreme weather event. More importantly, they lose working days, which means a tremendous loss of business for them.”

“A lot of companies are looking at their business continuity plans in a big way,” said Mehra, including relocating. During the floods many companies arranged for their employees to travel to Bengaluru and Hyderabad where they were accommodated for a few weeks before returning back to Chennai.

“This is definitely a cause for concern,” said Krishnamoorthy. “The fact that Chennai’s natural environment is taking such a hit, not only because of extreme weather but also because of rampant development, will definitely affect business in the long run. The city, which has a reputation of being great for business, will lose its sheen if things continue as is.”

The conflicting demand for water, food, and energy is one of the defining challenges of the 21st century. Global Choke Point, a collaboration between Circle of Blue and the Wilson Center, explores the peril and promise of this nexus with frontline reporting, data, and policy expertise. “Choke Point: Tamil Nadu” is supported by the U.S. Consulate General in Chennai. Jayshree Vencatesan of Care Earth Trust, Nityanand Jayaraman, and Amirtharaj Stephen provided expertise and invaluable guidance.

Sibi Arasu is an independent journalist based in Chennai. Follow him on Twitter @sibi123.

More Choke Point: Tamil Nadu

Read the full series of reports on the global implications of water, energy, and food challenges in the south India state of Tamil Nadu.

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A7610-2500.jpg

1600

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2018-07-03 15:03:082019-06-24 15:35:12Chennai’s Security Tied to Cleaning Up Its Water

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A7610-2500.jpg

1600

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2018-07-03 15:03:082019-06-24 15:35:12Chennai’s Security Tied to Cleaning Up Its Water https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2015-02_C4A4885-DMalhotra-2500-e1498222900407.jpg

1090

2042

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-06-23 08:52:432018-11-29 14:59:30This is Tamil Nadu

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2015-02_C4A4885-DMalhotra-2500-e1498222900407.jpg

1090

2042

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-06-23 08:52:432018-11-29 14:59:30This is Tamil Nadu https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A5938-2500.jpg

1366

2048

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-06-14 06:42:312017-08-22 12:19:45Mindful of Water Scarcity, Cost, and Pollution, Tamil Nadu Turns to Sun and Wind Power

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A5938-2500.jpg

1366

2048

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-06-14 06:42:312017-08-22 12:19:45Mindful of Water Scarcity, Cost, and Pollution, Tamil Nadu Turns to Sun and Wind Power https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A6606-2500.jpg

1667

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-06-06 15:56:442018-12-04 13:51:22India’s Toxic Trail of Tears

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A6606-2500.jpg

1667

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-06-06 15:56:442018-12-04 13:51:22India’s Toxic Trail of Tears https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-01-India-KSchneider-51530028-logo-2500.jpg

1262

2048

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2017-05-31 12:34:282019-04-01 10:41:31Pursuing Riches, Miners Plunder Tamil Nadu’s River Sand

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-01-India-KSchneider-51530028-logo-2500.jpg

1262

2048

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2017-05-31 12:34:282019-04-01 10:41:31Pursuing Riches, Miners Plunder Tamil Nadu’s River Sand https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-01-India-bottled-water-KSchneider-IMG_6676-logo-2500.jpg

1180

2048

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-05-24 13:12:552018-12-04 11:27:01The Right to Life and Water: Drought and Turmoil for Coke and Pepsi in Tamil Nadu

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-01-India-bottled-water-KSchneider-IMG_6676-logo-2500.jpg

1180

2048

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-05-24 13:12:552018-12-04 11:27:01The Right to Life and Water: Drought and Turmoil for Coke and Pepsi in Tamil Nadu https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A6151-2500.jpg

1667

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-05-12 07:18:152019-06-24 15:35:29In City Prone to Drought, Chennai’s Water Packagers Rush In

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A6151-2500.jpg

1667

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-05-12 07:18:152019-06-24 15:35:29In City Prone to Drought, Chennai’s Water Packagers Rush In https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2015-02_C4A5036-DMalhotra-2500.jpg

1366

2048

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2017-05-03 13:07:132018-12-04 11:19:10Rampage of Water and Social Entrepreneurs Push Chennai to Consider New Growth Strategy

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2015-02_C4A5036-DMalhotra-2500.jpg

1366

2048

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2017-05-03 13:07:132018-12-04 11:19:10Rampage of Water and Social Entrepreneurs Push Chennai to Consider New Growth Strategy https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A5709-2500-1.jpg

1667

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-04-19 12:16:272018-12-03 15:03:56Water Scarcity Causes Cauvery Delta Anguish

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A5709-2500-1.jpg

1667

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-04-19 12:16:272018-12-03 15:03:56Water Scarcity Causes Cauvery Delta Anguish https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A5854-2500.jpg

1439

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-04-11 08:41:062018-12-03 14:58:52Chased by Drought, Rising Costs, and Clean Technology, India Pivots on Coal-Fired Power

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-01-India-Tamil-Nadu-DMalhotra_C4A5854-2500.jpg

1439

2500

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2017-04-11 08:41:062018-12-03 14:58:52Chased by Drought, Rising Costs, and Clean Technology, India Pivots on Coal-Fired PowerThe conflicting demand for water, food, and energy is one of the defining challenges of the 21st century. Global Choke Point, a collaboration between Circle of Blue and the Wilson Center, explores the peril and promise of this nexus with frontline reporting, data, and policy expertise. “Choke Point: Tamil Nadu” is supported by the U.S. Consulate General in Chennai. Jayshree Vencatesan of Care Earth Trust, Nityanand Jayaraman, and Amirtharaj Stephen provided expertise and invaluable guidance.

Sources: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Central Electricity Authority (India), Circle of Blue, Community Environmental Monitoring, Enerdata, Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, Ministry of Coal (India), Public Finance Public Accountability Collective, The Times of India, U.S. Energy Information Administration, United Nations Environment Program.

Photo Credits: Used with permission courtesy of Dhruv Malhotra/Circle of Blue. Map and Graphics: Used with permission courtesy of Cody Pope/Circle of Blue.

Related

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy