CDC Releases Latest U.S. Legionnaires’ Disease Data

Report details cases from 2014 and 2015.

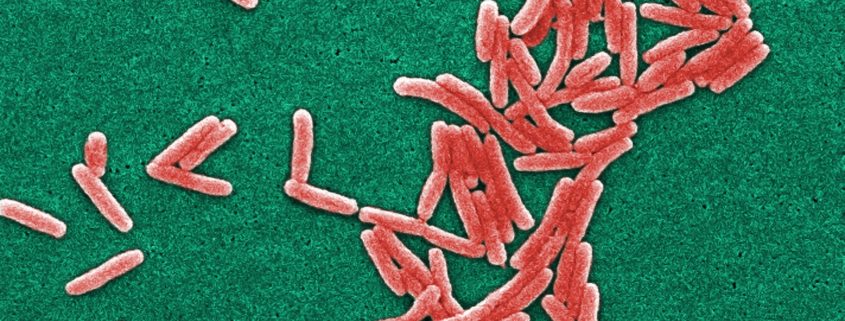

An electron microscope photo of Legionella pneumophila bacteria, the species that causes most Legionnaires’ disease cases. Photo via Janice Haney Carr/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Legionnaires’ disease, a pneumonia-like illness, is the deadliest waterborne disease in the United States, killing about one in eleven people it sickens.

There were 6,079 cases reported nationally in 2015 and 5,166 in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s first detailed report on Legionnaires’ disease occurrence. The rate of reported cases is rising rapidly, increasing four and a half times since 2000.

Provisional 2018 data, tallied through November 3, show a further increase: 7,104 cases, with eight weeks remaining in the year.

The CDC’s 2014-15 report presents detailed data that will be helpful for public health officials who are still trying to understand the rise of a disease that was identified only four decades ago, said Laura Cooley, the head of the CDC’s Legionella team. The report documents the states where the disease is most frequently reported, the types of people who are most susceptible, where they contracted the disease, and how many died.

Legionnaires’ is most common in people over age 50 and is most often contracted during the summer and early fall. Most reported cases came from the Great Lakes states and the mid-Atlantic region: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York.

“The geographic differences are of interest,” Cooley, a medical epidemiologist, told Circle of Blue. “There’s more to learn about why there are differences. Do diagnoses differ, or are there differences in the environment?”

Though the average death rate is one in eleven, it was nearly one in four for people who contracted the disease in a hospital or other healthcare facility. Hospitals have complex plumbing systems, which are risk factors for Legionella bacteria growth, while people exposed in these settings may already be ill or have weak immune systems, and thus be more susceptible to the disease.

Death rates are imprecise, though, and could be higher than reported, Cooley cautioned. A state or local health department might report the case to the CDC but not follow up with the outcome, which does not have the same reporting requirements as noting the onset of illness.

The report also revealed a deficiency in how doctors analyze Legionnaires’ disease, Cooley said. About 97 percent of patient diagnoses were made from a urine test. The rest were from cultures.

Urine samples are easier to obtain; cultures must come from phlegm that is coughed up.

Cultures, however, help researchers match the species of Legionella bacteria that cause the illness with environmental sources, Cooley explained. They are most helpful for doing investigative field work to trace an outbreak.

Diagnoses, too, could be improved. Legionella researchers assume that the number of actual cases is far higher than the number reported.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!