Counting Homes Cut Off From Water Is A Data Collection Nightmare

California utilities revolt against state attempt for more water shutoff information.

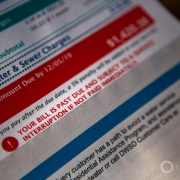

Water utilities do not collect shutoff data in a way that is helpful for understanding links to the rising cost of water service, researchers say. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Earlier this year, state regulators sent California’s roughly 3,000 community water systems an annual report that included what the authors thought was a reasonable question. How many times in 2017, the State Water Resources Control Board asked, had local providers turned off water to their residential customers?

What the question stirred instead was an information revolt, according to Max Gomberg of the Water Board. The data wasn’t there, utilities said. At least not in a useful format.

“We had systems saying, ‘We don’t track that,’” Gomberg told Circle of Blue. “They said, ‘We can give you a number, but we can’t tell you how many are repeat shutoffs, how many are because the households couldn’t pay, or how many are because the people may have moved.’”

The utilities, Gomberg recalled, were worried that the data would be wielded against them, to publicly shame them or make them look bad for turning off water. “It was a protest, if you will, to the question,” Gomberg said.

Shutting off a home’s water service can cause health problems and worsen a poor family’s financial distress. The data the Water Board sought are essential to understanding a crucial social justice issue in a state with, by one measure, the nation’s highest poverty rate due to high costs of living. A large number of shutoffs is seen as an indicator of a mismatch between the cost of water service and the ability of customers to pay for it. But how direct is the link? The Water Board wanted to gain a clearer understanding about how the rising cost of municipal water affects access to water for the poor.

The same data are also valuable to researchers who are trying to track the progress of the state’s six-year-old human right to water statute, a path-breaking law intended to ensure every state resident, regardless of their income, has “safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes.” The law resulted in substantial changes in water policy and practice.

“We don’t have a comprehensive idea of how many people are getting water shut off, which is why the Board is trying to collect data. And we really don’t know much about the causes for shutoffs,” Greg Pierce, a researcher at UCLA’s Luskin Center for Innovation who studies water affordability and access, told Circle of Blue.

A third consideration is that California water providers, in less than two years, will be obligated to track the number of water shutoffs as part of data reporting requirements. On September 28, Governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 998, which requires utilities, starting in February 2020, to post on their web sites and report to the Water Board the annual number of shutoffs for inability to pay. Shutoff data today is generally not publically accessible and must be gained through a public records request.

The Association of California Water Agencies, which represents large utilities, objected to the “inability to pay” language, arguing that its members may not know the reasons for a shutoff. However, Heather Engel, a spokeswoman, told Circle of Blue that the association will not challenge the requirement.

“It’s important for the state to know,” Gomberg said. “We know that drinking water costs are going up. People across the state are struggling with basic needs. If more people are getting water shut off, it’s a public health issue. That requires a policy response from the state.”

Imprecise Data Is A Common Problem

California water utilities are not the only ones splashing around in a shallow pool of shutoff data. Few utilities nationwide set up their billing systems and data collection processes to adequately parse their numbers, according to several recent reports and interviews with utility managers.

Disconnections, for instance, might have nothing to do with household poverty. Phoenix, with a resident population that fluctuates with the change of seasons, has homes that are empty for part of the year. “We have people who move in and move out,” Kathryn Sorensen, director of the Phoenix Water Department, told Circle of Blue. “You have to look carefully at the numbers. A shutoff for nonpayment is not necessarily indicative of affordability problems. People leave town and forget to make arrangements. Or, they’re too wealthy to be bothered with such details.”

Utilities turn off water service when customers do not pay their bills on time. Every utility has different protocols for when the disconnection occurs and how much residents must pay to get their water turned on again. Before shutting off service, most utilities make several attempts to contact the homeowner, and some offer repayment plans.

Food and Water Watch, a prominent national research and advocacy group, tried a fresh approach earlier this year. To get a handle on the most basic data — the number of shutoffs — the group sent requests to the two largest water utilities in each state. The group asked for the number of residential households disconnected from water service in 2016 and the number of residential accounts.

Seventy-three utilities responded. Shutoff rates — the number of shutoff households divided by the number of accounts — varied widely, according to Food and Water Watch’s report, which was published in October. Rates ranged from 23 percent in Oklahoma City and 20 percent in Tulsa, to 1 percent in Baltimore, Boston, and Dallas. Three utilities — Eau Claire, Wisconsin; Leominster, Massachusetts; and the Champlain Water District in Vermont — did not shut off any homes in 2016.

After comparing the number of shutoffs with economic factors, the Food and Water Watch researchers found connections in the high-shutoff cities to poverty, household income, and unemployment. But overall, they found it difficult to draw national conclusions with the limited data: “Overall, the shutoff rates have no obvious direct association with poverty rates, bottom household income quintiles, or unemployment rates. There are likely too many other various factors that influence shutoffs, including housing characteristics, water bill burdens, and local policies.”

Even Food and Water Watch’s relatively straightforward request was more detail than some utilities could provide. Instead of the number of unique homes shut off, 15 utilities provided the total number of shutoffs. Total shutoffs could include a single home being cut off multiple times, which would inflate the figures.

“We didn’t often get more data or more fine-tuned data than what we asked for,” Mary Grant, the lead researcher on the report, told Circle of Blue.

“They said, ‘They should just go to the Detroit River and get their water,'” said Baxter Jones, a wheelchair-bound Detroit resident, referring to statements made by city officials. “That’s just a mean-spirited thing to say to people.” Jones was among 19 people arrested for civil disobedience when they blocked crews from shutting off residential water connections in July 2014. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Another water research group ran into the same obstacles. A report published at the end of October by the Pacific Institute, an Oakland-based organization, looked at shutoff rates for 15 California utilities. While most had shutoff rates below 4 percent, one small utility in the Central Valley disconnected three in 10 households.

Laura Feinstein, the report author, urged caution in interpreting the data because utilities count shutoffs in different ways and not all shutoffs indicate overwhelming water bills.

“Our goal was to put out the little bit of information we had to frame the debate, to point out that it is worth exploring further,” Feinstein told Circle of Blue.

Feinstein’s top recommendation is for utilities to submit consistent, comparable data. At minimum, utilities should document whether a home is occupied or unoccupied when water is shut off. They could also report data monthly, which would identify homes with multiple shutoffs, and track how long water is turned off.

Some of those recommendations are being employed elsewhere. The Detroit Water and Sewage Department, maligned for mass shut offs in 2014 that affected thousands of households, now instructs its shutoff crew to note whether the home appears to be occupied.

Since it began tracking data this way in May, the department has deemed 39 percent of homes where it disconnected water service to be vacant. Because the assessment is done from the street, the number is a crude estimate, acknowledges Bryan Peckinpaugh, a department spokesman.

“It could be more or less, because the vacant number is done by visual check from the outside of the property,” Peckinpaugh told Circle of Blue.

In California, the State Water Board scrapped the initial data-gathering plan from earlier this year. The Board is now working with a group of three dozen utilities and non-governmental organizations to develop a better way of tracking and collecting shutoff data, something that the utilities requested.

“Moving forward, any data requests should be well-formulated and amply vetted through an open and transparent stakeholder process. The current one-sided closed process is unlikely to result in improved data quality or a better informed process,” wrote Michael Carlin, deputy general manager of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission in a letter to the Water Board on May 31, 2018.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power is one of the utilities in the working group.

“LADWP is cooperating as an active participant in [the Board’s] stakeholder group working to develop guidelines for reporting data. The group meets monthly in Sacramento and LADWP will continue to be a part of the ongoing conversation through 2019,” said Christina Holland, a spokeswoman, in a statement emailed to Circle of Blue.

LADWP did not want to comment on its data collection methods while still in discussion with the working group.

It is a data collection nightmare, and the process from the State level was broken from the start. The State Board reps and EJ community continuously fail to listen to the water community experts until there is sufficient push back, then go, oh yeah, it’s broken. Water cost is just one small facet of the affordability issue for many in CA, the smallest, yet the State continues to stick it’s head in the sand and ignore all the other pressures of living here. For instance, the gas tax and vehicle fees significantly increased the costs for the low income, as they tend to drive the furthest for work (e.g., construction and service industry workers), thus paying a larger amount of limited income to gas/fees, which only exacerbates exponentially all other areas of affordability. As mentioned in the article, there are so many facets and reasons water is shut off, from businesses going out of business, homes being unoccupied, renters skipping out, poor money management, etc, it’s hard to get it all collected. Glad the board and others are working with ACWA to figure it all out, as they should have from the beginning.