Despite its abundance, is groundwater a second-class citizen?

By Gary Wilson, Detroit Public Television’s Great Lakes Now

When you’re surrounded by the Great Lakes, there’s a tendency to fix your focus on them when the subject is water.

Why not?

The Lakes supply drinking water to millions, provide multiple recreational opportunities and are a coveted natural resource asset for future economic activity in the region.

For example, tech-giant Foxconn Technology is building a new plant in southeast Wisconsin that could bring up to 13,000 jobs because of its proximity to Lake Michigan.

In Michigan, water and the Great Lakes are literally the state’s public identity.

But what about a hidden water source that’s sometimes referred to as the Sixth Great Lake? A source so plentiful that it’s approximately the size of Lake Huron.

It’s groundwater.

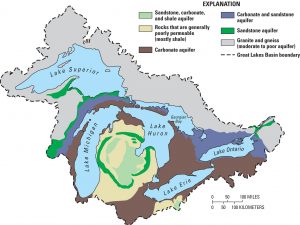

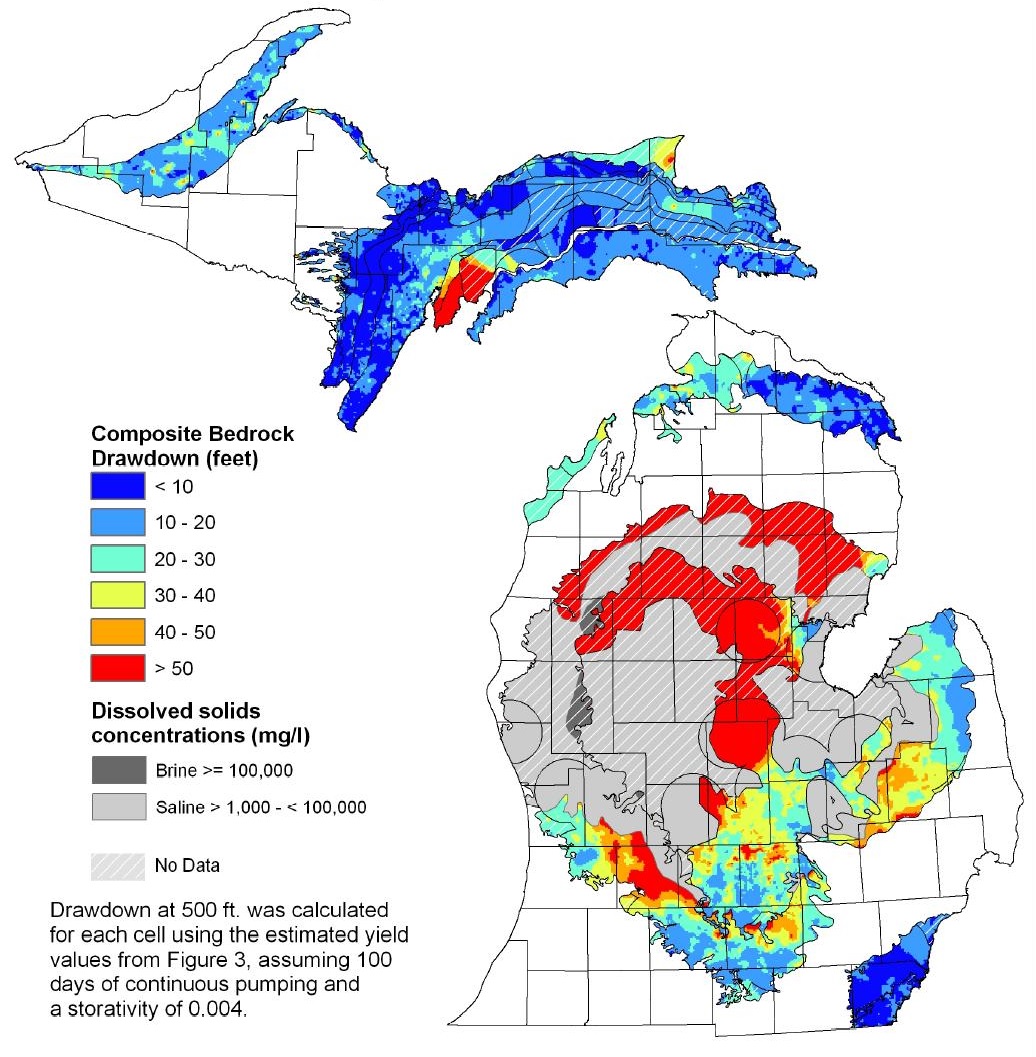

In Michigan, groundwater is buried out of sight in rock layers that serve as aquifers.

Almost half of Michigan citizens are served by groundwater, and the state uses 700 million gallons of groundwater each day, according to a Department of Environmental Quality fact sheet.

Public water supplies in Michigan provide groundwater to 1.7 million people and the state has nine percent of the nation’s groundwater supply systems, the highest share of any state the DEQ says.

What does the public know about groundwater and its quality? Are we locked into an out of sight, out of mind mentality until there’s a problem like the emerging PFAS issue?

Perhaps most important, is Michigan a good steward of its vast reserve of groundwater?

“Good programs”

“I think Michigan has good programs in place to foster groundwater stewardship,” Michigan State University’s Ruth Kline-Robach told Great Lakes Now.

“But we need to do a better job of publicizing those programs and encouraging communities and residents to proactively protect their groundwater supplies, which serve as a drinking water source for nearly half of Michigan’s residents,” she said.

Kline-Robach is a Water Resources Outreach Specialist in Michigan State’s Institute of Water Research where she focuses on community sustainability.

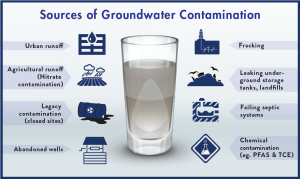

She cited legacy contaminants like PFAS among the risks to groundwater and stresses that local health departments play an important role in protecting it.

“Overall, we are fortunate to have abundant supplies of good quality groundwater in this state,” Kline-Robach said.

Critical report

However a Michigan activist group is raising a huge red flag on groundwater.

“Michigan is the Great Lakes state but is a poor steward of the sixth Great Lake- the water lying beneath Michigan’s ground,” Traverse City water nonprofit FLOW says in a groundwater position paper the group released this week.

“For a resource so vital to human health and the economy, Michigan’s groundwater is shabbily treated in both policy and practice,” the report said.

The 20-page document cites a history of Michigan neglecting groundwater including:

- Being the only state that lacks a statewide law to protect groundwater from septic tank pollution.

- Michigan has over 3,000 groundwater sites whose contamination is so severe that state law bars further use.

- There are approximately 1,100 locations where contaminated groundwater “known to the state” is legally flowing to lakes and streams with little or no treatment.

“Groundwater should not be society’s subsurface wastebasket,” the report says.

The FLOW report has a list of recommendations to remedy Michigan’s groundwater problems including a long-term funding commitment for cleanup of contaminated sites and a “statewide sanitary code,” which it says is “the most basic of protections.”

Separate from the FLOW report, Great Lakes Now asked Michigan’s DEQ to comment on the biggest threats to groundwater quality.

The agency articulated naturally occurring threats like arsenic, manganese, radium and microbial contaminants that it said “have had a big impact on public water supplies,” according to spokesperson Tiffany Brown.

Brown said man-made contamination like nitrates and volatile organic compounds also impact public water supplies. She said DEQ encourages communities to develop wellhead protection programsdesigned to prevent pollution from entering water supplies.

Brown emphasized that public water supplies like municipalities in Michigan “are required to monitor water quality.”

Because Michigan is the water heartbeat of the Great Lakes region, it will always be in the spotlight when issues emerge.

But other states struggle with groundwater too.

In Wisconsin in 2014, environmental groups asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to use its authority to investigate groundwater pollution from large-scale farming operations based on local concerns for water quality.

The Wisconsin DNR then facilitated a Groundwater Work Group in 2015 of interested parties to work on the problem.

As a result of that Work Group report, the “DNR revised the administrative rule that will strengthen nonpoint source pollution performance standards. This needed measure was thoroughly laid out, including public input, in a timeframe considerably less than most rules due to the critical nature of the issue,” spokesperson James Dick told Great Lakes Now.

Waukesha, Wisconsin was the site of the first major diversion of water from the Great Lakes basin under provisions of the Great Lakes Compact, the regional agreement designed to prevent diversions.

Different kinds of bedrock in aquifers can cause differences in how quickly groundwater recharges, Image by Granneman via USGS

Waukesha sought Lake Michigan water because its wells are contaminated with radium to the point that it was ordered to find another source of water.

In 2016 the U.S. and Canadian International Joint Commission (IJC) released a groundwater report on the Great Lakes region that said groundwater needed to be better “monitored and mapped” and to determine the impacts contaminants have on water quality, which suggests they weren’t adequately known or understood.

A 2009 Canadian report focused on Ontario called management of groundwater one of the most pressing challenges in Canada. And a 2010 IJC Science Advisory Report on groundwater said over 8 million people in the region rely on groundwater for drinking water including 82 percent of the rural population.

Minnesota challenges farmers

In environmentally progressive Minnesota, Gov. Mark Dayton has been direct in holding farming interests accountable for water quality.

Governor Mark Dayton visits Moorhead to view flood preparations, Photo by Sgt. Eric Jungels via wikimedia

In 2015, Dayton proposed a plan to curb farm pollution of drinking water where he asked farmers to “look into their souls” if they opposed his plan. He said they had a right to operate their farms for “lawful purposes” but that didn’t include contaminating water.

Following the Toledo water crisis in 2014, nitrate pollution in Des Moines and Flint’s ongoing problems, Minnesota commissioned an independent examinationof how it protects drinking water including groundwater.

The result was a 2016 report by the Minnesota Department of Health that identified problem areas and needs especially related to water quality staff.

The report said during a crisis, local staff would not “be likely to benefit from the added public attention and allocation of resources if or when crises occur.”

“They need the support of guiding policies, adequate funding, and public and political demand to drive the prioritization of this work,” the report said.

New governor in Michigan

Michigan will have a new governor in 2019, either Republican Bill Schuette or Democrat Gretchen Whitmer.

The Whitmer campaign’s website has extensive plans for water if elected under a heading titled “Cleaning Up Our Drinking Water.”

Without referring to groundwater, the site says Whitmer will “put people to work cleaning up drinking water contamination.”

Under a “PFAS Cancer Contaminants” heading Whitmer’s site says she will create “a statewide, publicly available database of all known groundwater resources and contaminated aquifer systems across Michigan.”

Schuette’s campaign site without mentioning groundwater, says he will “continue to ?ght for safe drinking water in every Michigan community.”

On PFAS, the site says Schuette will “work with the legislature, partners in the health, environment and business sectors, and the federal government to implement state clean-up efforts, resolve this problem, and ensure safe drinking water in our homes and communities.”

The challenge for the winner will be to turn campaign talking points on groundwater into action that protects Michigan’s drinking water.

–––––––––––––––––

To access the FLOW report on groundwater go to: www.flow.org. For more information on Michigan’s groundwater go to: Groundwater Statistics

Featured Image: Bedrock Aquifers – Estimated Drawdown, Image by egr.msu.edu

Gary Wilson is an independent journalist who focuses on the Great Lakes and related environmental, economic and social issues.

He wrote the Chicago View column for Great Lakes Echo and served as a commentator for Detroit Public Television’s Great Lakes Week coverage. Gary comments for the Great Lakes Month in Review segment on WKAR in Lansing and is an occasional contributor to WMUK in Kalamazoo.

Though Gary covers a wide range of Great Lakes issues, he is best known for his coverage of Great Lakes restoration, the Waukesha water diversion and the Toledo and Flint water crises.