Report outlines state’s failure to protect the ‘Sixth Great Lake.’

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue – September 25, 2018

Arnie Leriche holds a map of groundwater pollution plumes coming from the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base, in Oscoda, Michigan. Leriche, a community advisory board member who is involved with the site cleanup, stands in a field that was used for firefighting training at the base. The site is one of the major sources of PFAS chemicals into the area’s groundwater, rivers, and lakes. (Photo by J. Carl Ganter/CircleofBlue.org)

Verdant on a late summer evening, Clark’s Marsh, an old bend in the Au Sable River, is a fine spot for a walk, and the river is a fine spot to hook a trout. That natural beauty drew Arnie Leriche to this place.

After Leriche retired from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency he moved with his partner to Oscoda, the town just downstream from the marsh, with the idea that he would spend his work-free years fishing the clear waters of northern Michigan.

Trouble is, the marsh is just downstream from the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base, where toxic PFAS chemicals have been leaking into groundwater for decades from a field that was formerly used for firefighting training. The groundwater, tainted by foams used to put out the fires, seeped into the marsh, then into the river, and on down the watershed, even into Lake Huron. A few years ago, the Michigan Department of Community Health issued a warning to anglers: Do not eat the fish from the marsh.

Leriche, knowing a bit about pollutants from his years at the EPA, began to worry. Tests showed chemical concentrations in pumpkinseed and bluegill fish to be more than 15 times higher than state standards.

“When I heard the news of ‘Do not eat the fish’ I knew it was more serious than most,” Leriche recalled while walking his golden retriever Molly along a berm in the marsh. “I don’t know if I’d make a comparison to Love Canal,” – an infamous New York waste dump discovered in 1976 that spurred the federal Superfund program – “but it’s so significant that I knew that it was going to be a long-term, hard road for all the agencies and the communities. And, that’s what’s turned out to be over the last five years.”

Wurtsmith is one entry in a long and varied ledger of contaminated sites in Michigan that are contributing to a state groundwater emergency that has spilled over into rivers, streams, and lakes. The extent of this contamination and the failure of state agencies and lawmakers to muster a response equal to the challenge are detailed in a report from FLOW, a Traverse City-based water advocacy group.

Groundwater in Michigan, what FLOW is calling a sixth Great Lake, is “compromised and deteriorated,” the report asserts. Threats come both from legacy sites and current practices: abandoned industrial sites, military bases, dry cleaning facilities, landfills, septic tanks, underground tanks that store petroleum fuels, and fertilizers spread on farm fields. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality has identified more than 4,000 potential sites where contaminated groundwater and soil could release toxic vapors into buildings. Other connections are just as hard to see. Excessive groundwater pumping in fast-growing Ottawa County has been found to worsen water quality because it pulls deeper, saltier water into wells.

The report criticizes Michigan on two fronts: for inconsistent policies that over decades allowed pollutants to accumulate in groundwater reserves, and for failing to provide adequate funds for cleanup.

“Groundwater is treated as a place where wastes go, not a place to keep wastes out,” Dave Dempsey, the report author, told Circle of Blue.

A concrete pad where firefighting training took place at the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base is ground zero for Oscoda’s PFAS contamination. Foams sprayed here seeped into groundwater that has spread the chemicals to the area’s rivers and lakes. (Photo by J. Carl Ganter/CircleofBlue.org)

A Multitude of Threats

Why write the report now? The timing, Dempsey said. He noted that the discoveries of PFAS chemicals in dozens of locations around the state, from Oscoda in the northeast to Parchment in the southwest, increased public awareness of groundwater, which, in turn, has put pressure on public officials to respond. Second, state elections are in November and a new administration will come to power next year.

“It all adds up to a chance for a new governor to take action on one of our most important water issues,” said Dempsey, a senior adviser at FLOW and environmental adviser in the 1980s to former Gov. James Blanchard.

The to-do list is long, as the FLOW report points out, citing state data. The Michigan Office of the Auditor General found in a March 2017 assessment that the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) lacks funds to clean up 7,313 contaminated sites that affect water and soil. The $685 million Clean Michigan Initiative, a bond that voters approved in 1998 to fund the cleanups, ran out of money at the end of 2017. That money was also used to pay the state’s share of Superfund cleanups.

“Without additional funding, contaminated soil and water sites known to DEQ as posing a health risk to humans and the environment will go untreated,” the audit states.

Securing a new funding source is one of outgoing Gov. Rick Snyder’s priorities for the last months of his term. Snyder has proposed an increase to the fee for dumping waste at a landfill, from $0.36 per ton to $4.44 per ton. The fee would generate an estimated $45 million a year for cleanups.

“It would be a welcomed step, if enacted,” Dempsey said, even though FLOW supports another bond measure instead. Still, the dollar amount proposed by the governor is roughly equal to the $50 million a year that FLOW recommends in the report.

Some sites have been left to fester for decades. James Clift, policy director at the Michigan Environmental Council, criticized the Clean Michigan Initiative for prioritizing actions that leave groundwater pollutants in place, essentially fencing them off underground instead of removing them. It may be cheaper and more expedient than removal, but those chemicals can reemerge, sometimes as toxic vapors that waft into building basements.

“We’re not looking at longer-term problems when keeping it in place,” he told Circle of Blue.

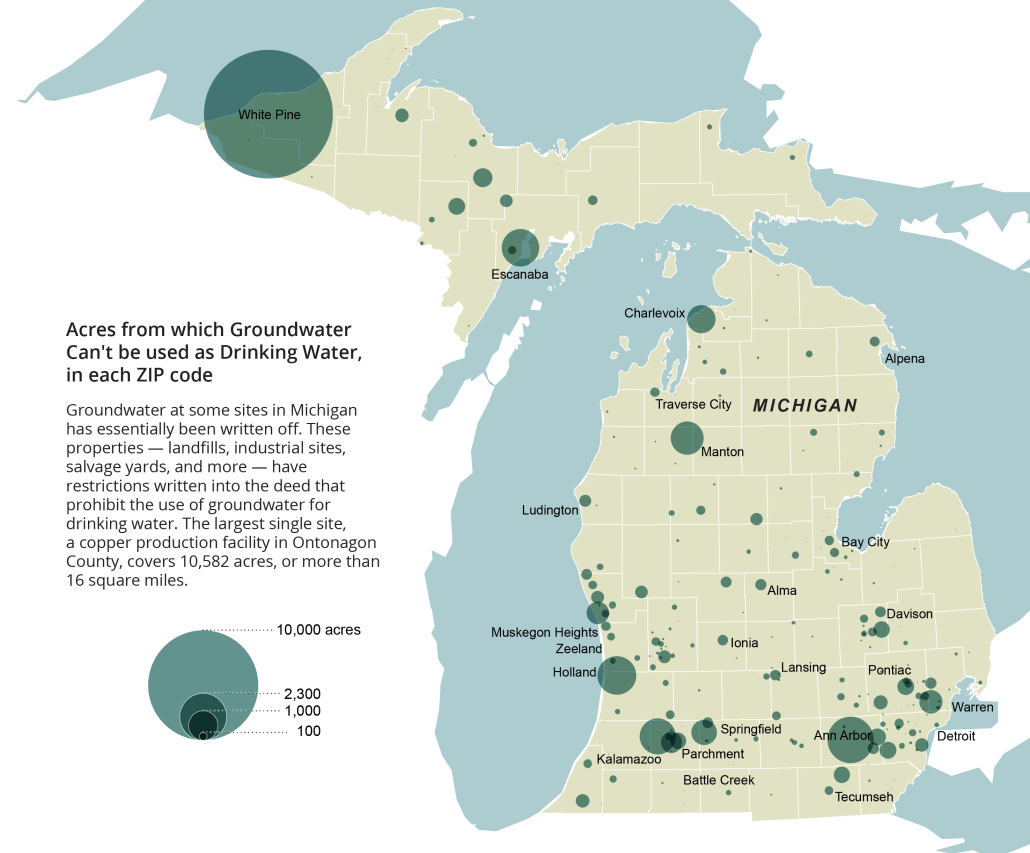

Groundwater at other sites has, in effect, been written off. The state has put restrictions that prohibit the use of groundwater for drinking water on the deeds of 2,239 properties, ranging in size from fractions of an acre to thousands of acres, because of existing contamination.

The scale of the problem can be staggering. In Mancelona, a plume of groundwater laced with trichloroethylene (TCE), a grease cleaner, has spread six miles from a former auto parts manufacturer that operated from 1947 to 1967. It is one of the nation’s largest TCE groundwater contamination sites. Wastewater from the facility was dumped in unlined pits, from which the chemicals percolated into groundwater.

The DEQ, which is funding the cleanup because the company went out of business, estimates that 13 trillion gallons of groundwater, down to depths of 500 feet, have been contaminated. The plume is moving northwestward at roughly 320 to 400 feet per year. The state paid to extend the public water supply system to 500 homes whose wells were tainted.

“It’s always a challenge to have enough staff and resources to address the need,” Andrew Hogarth, former chief of the DEQ remediation and redevelopment division, told Circle of Blue. Hogarth retired nine years ago after managing contaminated site cleanups for the state. New contaminants of concern are always cropping up, which adds to the cost: “PFAS was not even on our radar 20 years ago,” he said, referring to the year in which voters approved the Clean Michigan Initiative.

These slow-moving, widespread contamination zones are a risk especially for the 2.6 million Michigan residents who rely on household wells for drinking water. Well water is unregulated, and it is the homeowner’s responsibility to ensure their water is safe to drink. Dempsey and FLOW recommend a state fund to assist private well owners with water testing, which can cost hundreds of dollars per sample for volatile organic chemicals like TCE.

Map © Erin Aigner

The report offers a number of other recommendations to protect groundwater, most of which require the Legislature to pass new laws: minimum statewide standards for septic systems or a long-term funding source for cleanups.

Some of the recommendations are vague, such as actions to control nitrate pollution. Neighboring states like Ohio have enacted laws that prohibit spreading manure on snow-covered soil, to reduce the chance of runoff. But agriculture specialists question whether those restrictions will be effective. Farmers will still need to dispose of manure, said Erica Rogers of Michigan State University Extension who works with livestock producers. Holding it back may result in a buildup of manure in storage that needs to be dumped quickly or shipped out of state, she said.

Existing laws do allow for state oversight. Michigan’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act, passed in 1994, defines groundwater as a water of the state that requires protection. The linkage is sometimes ignored in practice, though. State standards for PFOS where groundwater discharges to streams or lakes have not been met in Oscoda. The tools are there but the state hasn’t had the political will to apply them as strongly as it could.” Nick Schroeck, University of Detroit Mercy

“The tools are there but the state hasn’t had the political will to apply them as strongly as it could,” Nick Schroeck, an environmental law expert at the University of Detroit Mercy, told Circle of Blue. “Plus the courts and the Legislature have become more skeptical of regulation and see it as a burden on the state economy.”

What is swept underground often does not stay there. Like a river, groundwater moves – and carries pollutants with it, either upward into drinking water wells or outward to rivers and lakes. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that 35 percent of the water in Lake Michigan originates as groundwater.

“Groundwater is treated like a second-class citizen because the connection to surface water is not seen,” Dempsey said.

Those hydrologic connections are evident in Oscoda, where residents are furious that the state and the Air Force have not done more to halt the flow of PFAS coming from Wurtsmith.

The base is “bleeding,” as residents are keen to say. And they want it stopped.

“We’re based on pure Michigan, right? That’s our motto,” says Cathy Wusterbarth, alluding to the state’s marketing slogan.

Wusterbarth, who was born in Oscoda, helped organize Need Our Water, a local activist group. “We’re the Great Lakes state. I’ve never questions the purity of our Great Lakes until now. When I’ve seen the pumping of this contamination and what I know it does to our health, it has changed my attitude on the preservation of water in our area.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton