Regulators Will Soon Know A Lot More About Algal Toxins in U.S. Drinking Water

For the next two years, water utilities are required to test for ten cyanotoxins.

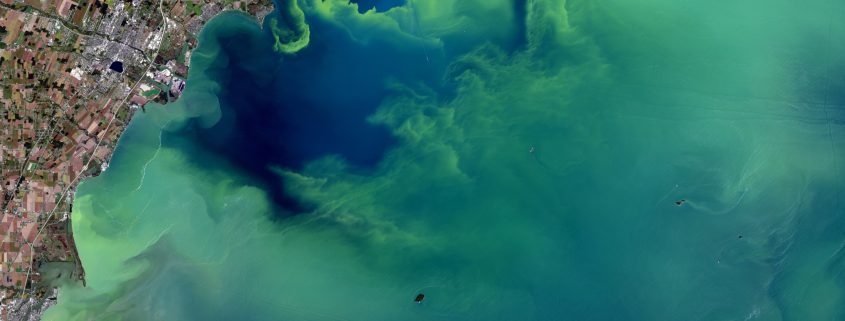

An algal bloom swirls in the western basin of Lake Erie, in September 2017. Photo courtesy of USGS/NASA

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Authorities in Salem, Oregon, lifted a drinking water advisory on July 3 that had been in place for children and the elderly since Memorial Day weekend, when algal toxins were discovered in the city’s water system.

How many other water systems are at risk from the toxin-producing scum that grows in rivers and lakes, particularly in the warmer months? Thanks to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency monitoring requirements, regulators will soon have more comprehensive data on how often such toxins show up in drinking water supplies and at what concentrations.

For the next two years water utilities are required to test for 10 cyanotoxins and their variants. The requirement stems from a Safe Drinking Water Act provision designed to help the EPA understand how frequently contaminants that are not regulated at the federal level appear in drinking water. The data are used when considering whether to set mandatory safeguards.

“It’s going to be helpful,” Alan Roberson told Circle of Blue. Roberson is the executive director of the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators, the organization that represents state water regulators.

Produced by cyanobacteria, nourished by excess nutrients, and amplified by warming temperatures, the toxic blooms are a growing health threat in drinking water, both for humans and pets. The toxins target the liver, nervous system, and skin, and can cause nausea, rashes, stomach pain, and in rare cases, death. The EPA established drinking water health guidelines in 2015 for two toxins — microcystin and cylindrospermopsin — but the guidelines are not enforceable.

To inform its regulatory decisions, the EPA periodically orders utilities to gather data on unregulated contaminants in their treated water. During this fourth assessment cycle, utilities must test for 30 such contaminants. In addition to cyanotoxins, the list includes the pesticide chlorpyrifos and metals like manganese and germanium.

The roughly 4,000 water systems that serve more than 10,000 people must participate in the testing. For smaller systems, the EPA randomly selected a group of 800 to monitor for cyanotoxins and another 800 to monitor for the other 20 contaminants.

Though testing of rivers and lakes to protect swimmers and boaters is common, few states require utilities to test drinking water for cyanotoxins.

Ohio is one of the leading states in addressing algal toxins, Roberson said. That leadership grew in large part from a shock: four years ago, the city of Toledo, which draws water from Lake Erie, made headlines for shutting down water service to some 400,000 people for several days due to detection of cyanotoxins. Blooms in recent years also fouled the Ohio River and dozens of lakes used as drinking water sources.

In Ohio now all utilities that draw water from rivers and lakes have mandatory cyanotoxin monitoring requirements. They also have to demonstrate the ability to remove cyanotoxins from drinking water.

When it issued the monitoring rules in June 2016, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency argued that it could not wait several years for its federal counterpart to gather data and write regulations — if federal regulators ever get to that point. The EPA determined in February 2011 that standards were needed for perchlorate, but the standards have not been finalized.

Though Ohio’s algae monitoring regulations are still quite new, they haven’t hurt. According to the Ohio EPA, since its rules went into effect no utility has issued a drinking water advisory for a harmful algal bloom.

“The rules provided regulators and system operators with greater awareness of the scale and scope of the problem,” James Lee, an agency spokesman, told Circle of Blue.

Oregon regulators, meanwhile, responded to the Salem incident by tightening their rules. The Oregon Health Authority issued testing requirements on July 1 for water systems that draw from sources that are vulnerable to algal blooms. The rules, which apply to 95 water systems, are a temporary, emergency patch until the authority goes through a public rulemaking process.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

>>The roughly 4,000 water systems that serve more than 10,000 people must participate in the testing.

Wow, massive effort. Looking forward to learning more!

Just because Cyanobacteria (fromerly Blue-green algae) are in the water does not necessarily mean there are toxins present. Certain strains contain toxins. One can only know if toxins are present is to test for them. If the EPA guidelines are not enforceable then municipalities will forgo testing to save money. The end result would be toxins affecting those who drink the water.

Can any tell me if cyanotoxins tests will be required in Alabama or Georgia and if so, what are the best means to do so.

Thank you