The country is using less water, but latest USGS report shows influences of California drought on national data.

U.S. water withdrawals continue to drop despite a growing population. Graphic courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

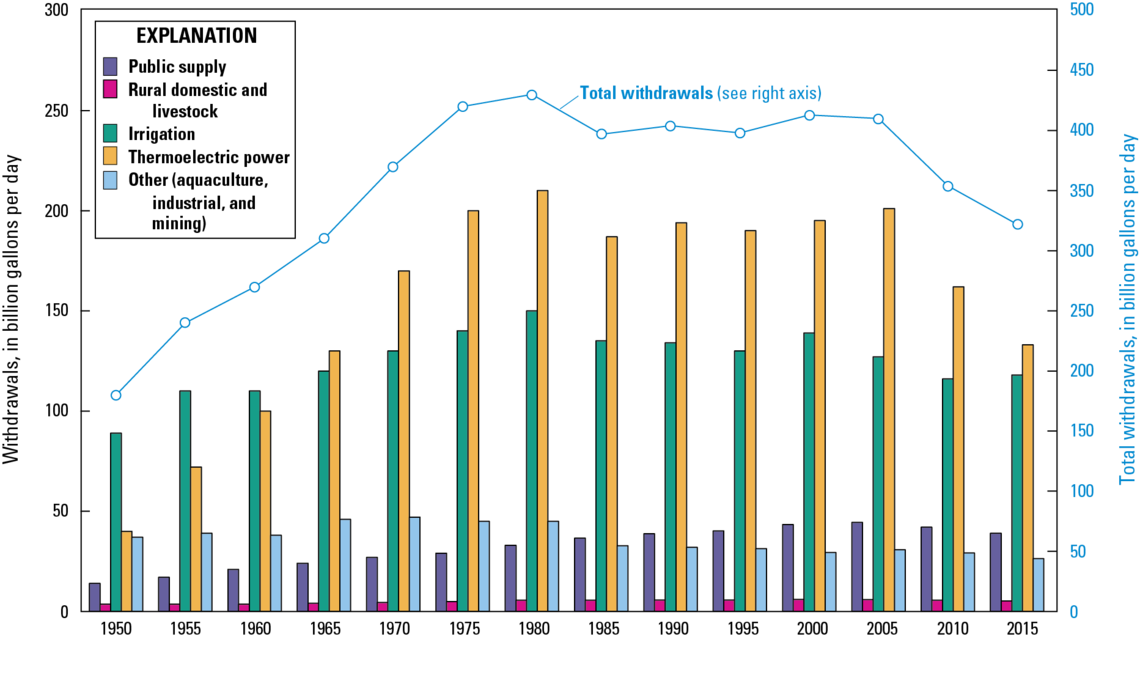

Even though the country is growing, U.S. water withdrawals dropped to the lowest level since before 1970 with steep declines for municipal and electric power sectors, according to a U.S. Geological Survey report.

Total withdrawals fell 9 percent compared to 2010 as the country’s population increased 4 percent.

The USGS report illustrates that the use of water in America’s economic and domestic spheres is on a radically different trajectory than it was a generation ago. Withdrawals peaked in 1980, flattened through 2005, and declined substantially in 2010 and 2015.

Every five years the federal government’s premiere natural resources science agency compiles a snapshot of how much water the country diverts from rivers, lakes, aquifers, and oceans to be used for power generation, mining, irrigation, aquaculture, households, and industries. The data are gathered from state, local, and other federal agencies. When reported numbers are not available, the USGS estimates the figures.

Water withdrawals for municipal use decreased in both absolute and relative terms in 2015. Total municipal withdrawals decreased by 7 percent. Average per person withdrawals were 82 gallons a day, compared to 89 gallons a day in 2010 and 99 gallons in 2005.

The USGS report does not look at what caused the changes. Other studies have shown that decreases in household use can be traced to tighter state and federal plumbing codes that gave rise to more low-flow showerheads and toilets, high-efficiency washing machines, and other water-wise appliances. Industrial water use has also been transformed by manufacturing plant closures and adoption of water recycling technology, which reduces fresh water demands.

Some caution is necessary in interpreting the data, Cheryl Dieter, the report’s lead author, told Circle of Blue. California was in the middle of its historic drought in 2015, and urban residents were under mandatory water use restrictions that year. Because the state is so large — it accounted for 9 percent of the country’s freshwater withdrawals — restrictions exerted extra influence on the national numbers.

Municipal use would have decreased regardless but the decline is perhaps steeper than it would have otherwise been, Dieter said.

Significant Changes in Electric Power Sector

Generating electricity from fossil fuel and nuclear power plants accounts for 41 percent of the water withdrawn in the United States, down from 49 percent a decade ago. This water is used to cool the facilities.

Home to older coal-fired and nuclear power plants that rely on a “once-through” cooling technology that pulls prodigious volumes of water from rivers and lakes, the Midwest and Southeast lead the country in electric power freshwater withdrawals.

These regions still top the charts, but states registered substantial reductions since 2010: Alabama (20 percent decrease), Illinois (24 percent), North Carolina (19 percent), Ohio (38 percent), and Pennsylvania (34 percent), to name a few.

None, however, could match the shift in Georgia, where fresh water for power generation dropped from 1.77 billion gallons a day in 2010 to 741 million gallons in 2015, a stunning 58 percent decrease.

All told, the electric power sector cut freshwater withdrawals by 22 billion gallons a day, or 18 percent.

Sara Barczak of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy explained that the decrease in the power sector is largely due to three factors: closure of coal plants, conversion to more-efficient natural gas plants, and replacement of once-through cooling systems with recirculating systems. Recirculating systems take much less water from rivers but lose more to evaporation. Thus, consumptive use can increase, which puts a different strain on rivers.

A report prepared in April by the Cadmus Group found that consumptive use by Georgia’s power plants decreased in the last decade, but that increases by 2050 are possible due to two new units at Vogtle nuclear plant and the potential increase in energy demand.

Once-through systems are vulnerable to low water levels in rivers which forced Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant in Alabama to shut down for a day in 2007. Barczak sees the reduced water withdrawals in a positive light, especially as temperatures rise.

“It’s a good development,” Barczak, who focuses on links between energy and water use, told Circle of Blue. “Reduced need for fresh water for electric needs in the Southeast is a benefit for the resiliency of the region as we see the effects of climate change play out.”

The California Effect

Not every sector posted declines, though. Fresh groundwater withdrawals increased by 8 percent compared to 2010. And irrigation increased by 2 percent.

Again, the California drought effect is to blame. Irrigation accounts for 70 percent of fresh groundwater withdrawals. Rivers and reservoirs were so depleted during the drought that California farmers pumped and pumped from aquifers. Fresh groundwater withdrawals in California for irrigation increased by 60 percent, while surface water withdrawals for irrigation in the state decreased by 64 percent.

In this report, the USGS also revived dormant data categories. The report estimated consumptive use by irrigation and electric power, data that had not been collected since 1995.

“This is an important part of the water budget,” Dieter explained. “How much you withdraw, but also how much is not available for other uses.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton