Atmospheric Rivers, Conveyor Belts of Extreme Moisture, Rack Up Heavy Flood Damages in Western United States

Researchers estimate $1 billion in flood damages annually in last 40 years from atmospheric rivers.

An aerial view of the damaged Oroville Dam spillway and the huge debris field below it, in a photo taken on February 27, 2017. A category 4 atmospheric river in February 2017 swelled the rivers that flow into California’s second largest reservoir. The damaged spillway cost more than $1 billion to repair. Photo courtesy of Dale Kolke / California Department of Water Resources

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Thunderstorms and monsoons, low pressure systems and tropical storm remnants. Rain comes from many sources in the American West, but none is as destructive as an atmospheric river, according to a new study that assesses flood damage caused by these conveyor belts of moisture.

Previous studies have established the fundamental role that atmospheric rivers play in water supply. The number of such storms in a given year determines whether California experiences severe drought or catastrophic floods. But much less was known about the economic costs of a storm system that can deliver an amount of rain equivalent to 25 Mississippi Rivers.

A team led by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography sought to change that. By combining data on weather events and insurance claims, the researchers were able to quantify the outsized influence of atmospheric rivers on flood damages. Their study was published online in the journal Science Advances.

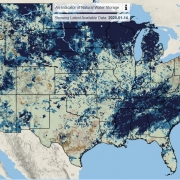

In 11 western states, all flood damages between 1978 and 2017 were reckoned to be $50.8 billion, according to the study. Some 84 percent of the total damages, or $42.6 billion, was attributed to atmospheric rivers. That amounts to about $1.1 billion annually in destroyed homes, roads, and property as a result of these “sky rivers.”

Atmospheric rivers that hit the U.S. west coast carry water vapor from the tropics, an origin story that gives them the nickname Pineapple Express. The moisture they carry is released as rain or snow when the storms are pushed over mountain ranges that extend from Washington to Baja California. Lasting three to 10 days, the most severe storms can deposit two feet or more of rain.

Patterns from the data indicate regions of greatest concern. The damage attributed to atmospheric rivers is concentrated on the coast and steadily diminishes farther inland. In Sonoma, Napa, and other coastal counties in northern California, more than 99 percent of all insured flood losses were caused by atmospheric rivers. Similar ratios were found in coastal Oregon and Washington.

As with most other natural hazards, a few significant events were responsible for the bulk of the devastation. The researchers catalogued 1,603 atmospheric rivers in the last four decades. But only 11 storms caused more than $1 billion each in damages. The most destructive storm, which hit central California in January 1995, totaled an estimated $3.7 billion in damages.

Like hurricanes, atmospheric rivers are rated on a five-point intensity scale. Each one-point increase corresponds to a 10-fold increase in economic damages, the study found. The median damages from a category 1 or 2 storm were less than $1 million, while damages from a category 4 or 5 could be hundreds of millions of dollars.

Timing and location are also factors in the outcome. For storms that hit areas with few people or infrastructure, little harm follows. Smaller storms are beneficial for water supplies and snowpack.

But when heavy rains encounter saturated soils, urban density, or prized assets, calamity can ensue. California water managers learned that lesson in February 2017, when a category 4 atmospheric river made landfall in the vicinity of Oroville Dam.

Oroville is the second-largest reservoir in California. The dam’s main spillway and emergency spillway were damaged as operators attempted to flush enough water to keep the dam from failing. Some 180,000 people downstream were evacuated. The cost of repairing the spillway topped $1 billion.

Though significant today, damages could increase in the future, the authors warn. Under a warming climate, atmospheric rivers are expected to grow larger and deliver more precipitation. At the same time, population growth and development will put more people and assets at risk.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!