In Australia, Echoes of Past, Glimpses of Future As Country Braces for Hot, Dry Summer

A record-breaking drought is pushing rural communities in New South Wales and Queensland to the breaking point.

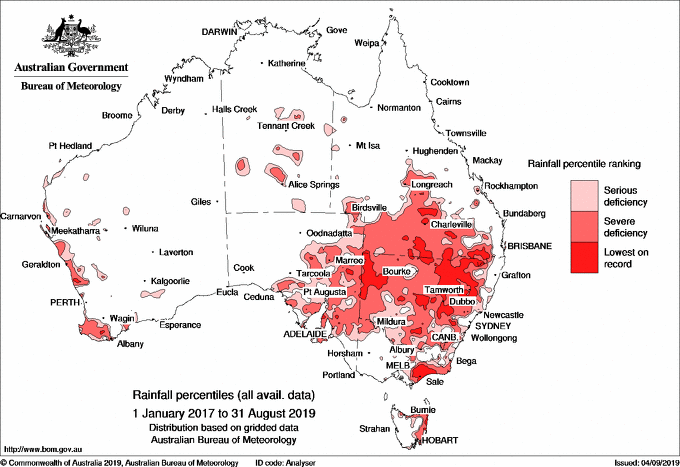

Parts of interior New South Wales and Queensland have seen the lowest rainfall on record in the last 17 months. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Water is so scarce these days in Murrurundi, a drought-tested town in the northern reaches of New South Wales, that it arrives by truck.

Murrurundi Dam, an off-channel reservoir that draws from the Pages River, is functionally dry. An emergency well provides a little local water, but half of the small community’s supply is now trucked in.

“I’ve never seen the Pages River this low,” Daele Healy, who has lived in town for 15 years, told Circle of Blue. “There’s just no water visible at all. Not even little ponds.”

A pair of trucks masquerade as a replacement river. They drive a half hour south, to the town of Scone, where they fill their loads and return with the liquid, which is stored in a holding tank before being treated, said Healy, a spokesperson for Upper Hunter Shire Council, the regional governing body. The truck drivers make three or four round trips each work day, she said.

Murrurundi, home to fewer than 1,000 people, is not the only place in eastern Australia where a withering three-year drought has pushed water supplies to the brink of exhaustion. The water authority for New South Wales noted that the Macquarie River, which supplies some 50,000 people in several communities, will dry up by next May if there are no significant inflows and residents do not dramatically conserve water.

“This drought is outside the history books,” Melinda Pavey, the New South Wales water minister, wrote last week. Pavey’s department has directed $130 million in funding to rural communities for emergency water pipelines and wells. Total drought aid from the New South Wales government, including farm support, infrastructure development, and mental health services, amounts to more than $1.8 billion.

The next few months are unlikely to bring relief. The Bureau of Meteorology forecast is for below-average precipitation and above-average temperatures through January. With hot and dry conditions, the potential for bush fires on the coasts of New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria is likely to be above normal, according to a national fire research center. Only a few days into spring in the southern hemisphere, Australians, especially those in the eastern states of New South Wales and Queensland, are already dreading a hot, dry summer.

Few livelihoods are untouched. Like Murrurundi, the Airly coal mine, operated by Centennial Coal, is importing water. Airly’s processing water now comes from a shuttered mine located some 25 kilometers (16 miles) north. Centennial moves the water via rail cars. Without imports, Airly would stop production and lay off employees, Katie Brassil, Centennial spokesperson, wrote to Circle of Blue in an email.

Farmers in the Barwon-Darling region face pumping prohibitions from the river, which is largely dry, while ranchers are culling herds and searching for feed. Due to declining harvests, Australia imported wheat this year for the first time in a dozen years.

Ecosystems are suffering, too. Warm, depleted rivers and lakes are ideal growing conditions for toxic algae. Dissolved oxygen in the water also diminishes. These conditions can be deadly for fish. A repeat of the die-off last January that killed hundreds of thousands of fish in the Darling River, near Menindee, could occur again unless government officials intervene, according to an independent commission’s report. The commission noted that the beleaguered Murray-Darling basin, the country’s largest river system, is under chronic stress from extraction of water for farming and from a drying climate.

Echoes of the Past, Window to the Future

In all, the three-year drought has eclipsed the severity, if not the length, of the seminal Millennium drought, a decade-long bout with aridity that was also called the Big Dry. Rainfall deficits in the last 17 months are the worst on record in parts of northeastern New South Wales, southern Queensland, and eastern South Australia, according to the Bureau of Meteorology. Much of this land falls within the Murray-Darling basin, where the 32-month rainfall deficit is also the worst recorded.

Rainfall deficits in the Murray-Darling watershed over the last 32 months are the worst on record. Graphic courtesy of the Bureau of Meteorology

“We thought the Millennium drought couldn’t get any worse,” Adam Lovell, executive director of the Water Services Association of Australia, told Circle of Blue. “But this has smashed the Millennium drought out of the water, no pun intended. It’s a really bad way.”

“Really bad” might also summarize Australia’s future in a warming climate. A special report on 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming published last year by the United Nations climate panel noted that Australia is one of the planet’s most vulnerable regions to freshwater scarcity and declines in food production as temperatures climb. Australia is also a relatively large contributor of greenhouse gases, with one of the highest rates of carbon emissions per capita. The Queensland government, earlier this year, approved the Carmichael mine, set to be one of the country’s largest coal operations.

Andy Pitman, director of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes, told Circle of Blue that inland New South Wales and Queensland, the centers of vulnerability in this drought, have seen strong drying trends over the last three decades. Warmer temperatures in the region are a clear consequence of the buildup of carbon in the atmosphere. But the same claim cannot yet be made about changes in rainfall, he said. There is too much natural variability to unthread.

“The temperature projections are clear,” Pitman explained. “Warming, heat waves that are more intense: everything points to serious problems. On temperature, there’s not a lot of good news.”

For Lovell, the changing climate is an argument for designing municipal water systems to cope with tightening constraints on natural flows.

“We need to build resilient communities,” Lovell said. Resilient, he continued, means diversifying water supply sources and investing in reuse. “Relying on rivers and dams for water supply — the future cannot look like that,” he said.

Old thinking lodges deeply, though. The Guardian reported that New South Wales officials are exploring the idea of redirecting coastal rivers inland, to soften water shortages in the interior. Such schemes have been discussed as far back as the 1930s.

The patterns of water vulnerability in Australia mirror those in California, which experienced a historic drought between 2012 and 2017. Rural communities, farmers without access to groundwater, and ecosystems confront the most severe risks. In Australia, the vulnerable communities in this drought are the towns, farmers, and river systems in inland New South Wales and Queensland.

Big cities on the other hand, are fairly well positioned. Sydney Water announced in January, after Warragamba Dam, the city’s main reservoir, dropped below 60 percent capacity, that it would restart its desalination plant. The plant, which last produced water in 2012, reached full production in late July, and is now providing about 15 percent of Sydney’s water supply. Combined with a little rainfall and conservation measures — utilities are making 4-minute music playlists to guide showering lengths — the city’s reservoir levels have stabilized, for the moment, at just under 50 percent full.

The operators of the desalination plant are working with the New South Wales government on an expansion plan, Philip Narezzi, the chief operating officer, wrote to Circle of Blue. If it goes through, the plant’s capacity would likely double, to 500 megaliters per day. Sydney Water is also aiming to double its recycled water supply over the next 25 years.

In Murrurundi, meanwhile, residents have been on Level 6 water restrictions, the most severe, for more than a year. No washing cars, no watering lawns, no filling swimming pools. They await a 40-kilometer pipeline that will connect the town to a regional water system. The $14 million project, which is largely funded by the state government, broke ground in August and Healy says it should be completed in mid-2020.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!