Depletion and pollution of Vietnam’s water supplies are hurting the country now, and could cause economic losses up to 6 percent by 2035, says new World Bank report.

Flood risks are growing, particularly here in the Mekong Delta and in Vietnam’s southern and central regions, according to a new World Bank report. Peak flood flows that used to occur every 100 to 500 years are now expected across half the country every 20 years or less within the next two decades. © J. Carl Ganter/Circleofblue.org

By Abedalrazq F. Khalil and Jennifer Möller-Gulland

HANOI — Vietnam’s economic growth and social stability face increasing risk of disruption due to water scarcity, flooding, and pollution, according the new World Bank report, “Vietnam: Toward a Safe, Clean, and Resilient Water System”.

Ample water supplies combined with open-market economic policies transformed Vietnam from an impoverished country to a rising middle-income nation within two decades. Now the fruits of success are starting to turn bad. Though growth has developed new markets for fish, agricultural, and industrial products, it has also placed unrelenting pressures on water resources, which are now straining the economy.

“Pressures from population growth, economic growth, and increasing water demand have put water resources at risk of depletion,” said Tran Hong Ha, Minister of Natural Resources and Environment, at the launch of the report on May 30, 2019. “These pressures will result in unsustainable development unless water resources are managed in a uniform and coordinated way and shared and used reasonably and effectively.

A traditional wooden boat plies the tributaries of the Mekong Delta near Can Tho, Vietnam. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Vietnam is one of the most hazard-prone countries in East Asia and the Pacific region, the report notes. More than 70 percent of the population is exposed to droughts, floods, and other water-related hazards, which are likely to increase due to climate change.

These threats, cascading though the economy now, are already causing damage. Economic losses, currently estimated at 1.5 percent per year, are forecasted to rise sharply: to 3 percent per year by 2050 and to as much as 7 percent by 2100, among the highest in the world.

Unless decisive steps are taken, water, which has been a driving force behind Vietnam’s rapid growth, will become a brake on development.

The 190-page report highlights a number of factors that are converging to produce worrisome trend lines:

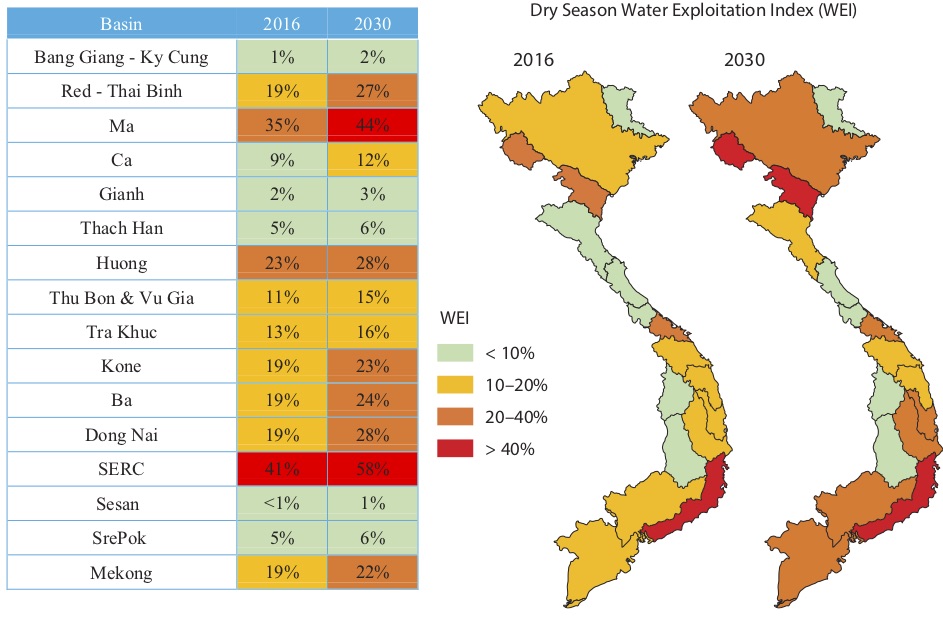

Vietnam faces an emerging mismatch between water supply and demand in the dry season.

If demand is unchecked and there is no change in policy or practice, all but five river basins are expected to face water stress in the dry season by 2030. This includes the four main river basins that generate 80 percent of Vietnam’s GDP.

Clouds darken the sky off of Vietnam’s southern coast, near the Mekong delta. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Deterioration in water quality, and pollution loads are rising, contaminating surface and groundwater and creating public health hazards.

Much of Vietnam’s wastewater is not treated before being discharged. Only 46 percent of urban households have connections to drainage systems and only 12.5 percent of municipal wastewater is treated. Around two-thirds of industrial wastewater from industrial zones is treated, while only 9.4 percent of industrial clusters have centralized wastewater treatment facilities. Elsewhere treatment is an afterthought. Most wastewater from 5,000 craft villages, some factories outside of industrial zones, and local hospitals and private clinics is discharged untreated to rivers, lakes, and oceans.

Water pollution from agriculture and aquaculture is increasing.

Agriculture produces vast quantities of waste from fertilizers, pesticides, pathogens, and pharmaceuticals that are fed to animals. Some 95 percent of livestock waste generated each year enters the environment untreated, carrying nutrients, pathogens, and volatile compounds that pollute water and air, and damage soils. Only about half of fertilizer is used effectively; the rest is washed out in runoff. The current mix of pesticides is also highly toxic, with 85 percent of pesticides used by farmers in the Red River Delta categorized as ‘highly hazardous’ or ‘moderately hazardous’ according to World Health Organization standards.

Solid waste from municipalities poses another threat to surface waters. Illegal dumping, unsanitary and badly managed dump sites near waterways, and a lack of solid waste collection allows a rising tide of plastics to reach waterways.

Flood risks are growing, particularly in the Mekong Delta and in the country’s southern and central regions. Peak flood flows that used to occur every 100 to 500 years are now expected across half the country every 20 years or less within the next two decades. Areas south of Danang, including the economic center of Ho Chi Minh City, are particularly at risk.

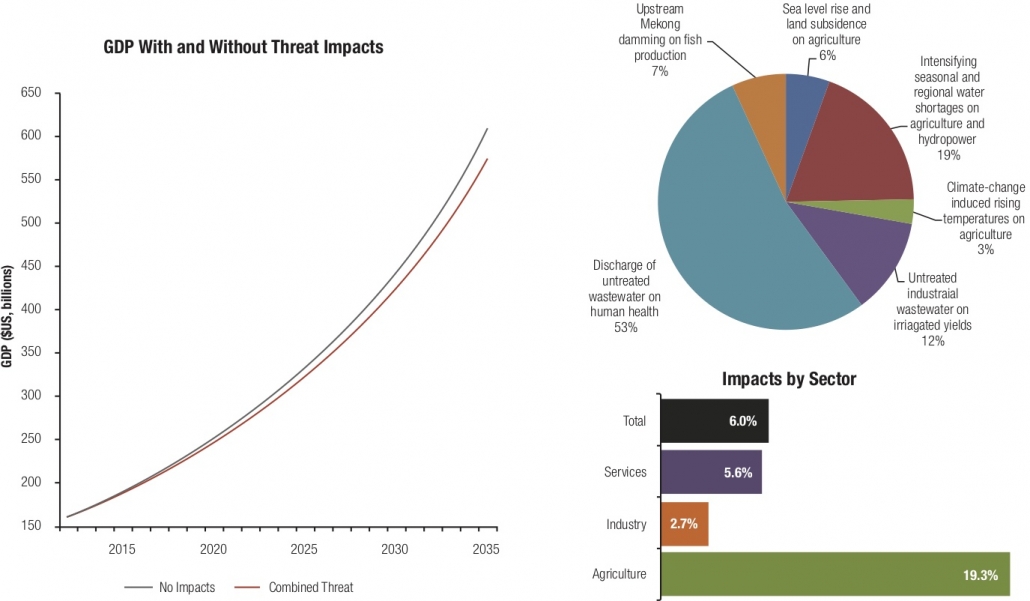

If there is a bright spot, it is that concerted and resolute action today can prevent the worst outcomes. The report further predicted that the rising level of water-related threats could reduce GDP by 6 percent by 2035 against a scenario in which steps are taken (see graph below).

The solutions suggested by the World Bank report are clustered around seven recommendations.

- Improve water resources management institutions.

- Manage Vietnam’s water at the basin scale through inclusive governance arrangements.

- Increase the value produced by water in agriculture.

- Give the highest policy priority to reducing the devastating levels of pollution.

- Improve risk management and disaster response and strengthen resilience.

- Develop and scale up market-based financing and incentives.

- Strengthen water security for settlements.

Meeting these challenges will call for a greater focus on policies and incentives, and for increased fiscal discipline.

Vietnam has sound water policies, but in practice they do not function as intended. Policy implementation is uneven, the incentives required to ensure better policy compliance are inadequate, and the institutional foundations needed to address the new generation of challenges are insufficiently developed. Likewise, while there is an acknowledged need to adopt integrated basin-wide approaches that manage water across sectors and protect the environment, implementation has been lacking. Going forward, greater emphasis will have to be given to policy enforcement and to the incentives needed to assure greater compliance.

Abedalrazq F. Khalil is a Senior Water Resource Management Specialist of the World Bank Water Global Practice, based in Singapore, leading the report.

Jennifer Möller-Gulland is a water economist based in Asia and key author of the report. She is also a contributing analyst for Circle of Blue.