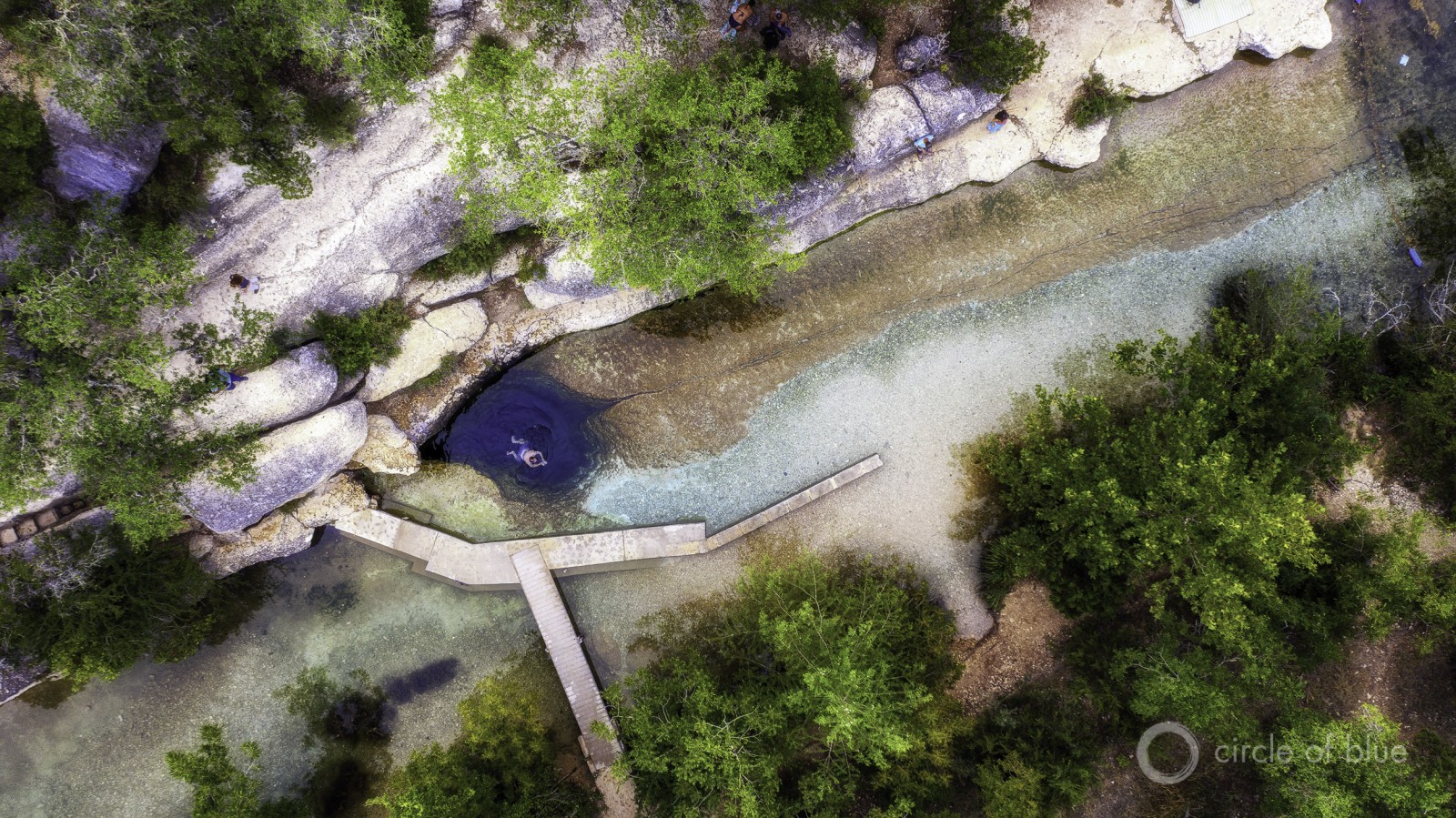

That may be true in Hays County. It’s not true downstream in the state’s Gulf Coast estuaries. Because less water drains from the Hill Country, some Gulf Coast estuaries — nursing grounds for sport fisheries, shrimp and oysters, and grassy resting and breeding grounds for migratory birds and water fowl — are shrinking. Texas wildlife and fisheries managers have been aware of this condition of water scarcity since the state’s population began increasing by 250,000 annually in the 1980s.

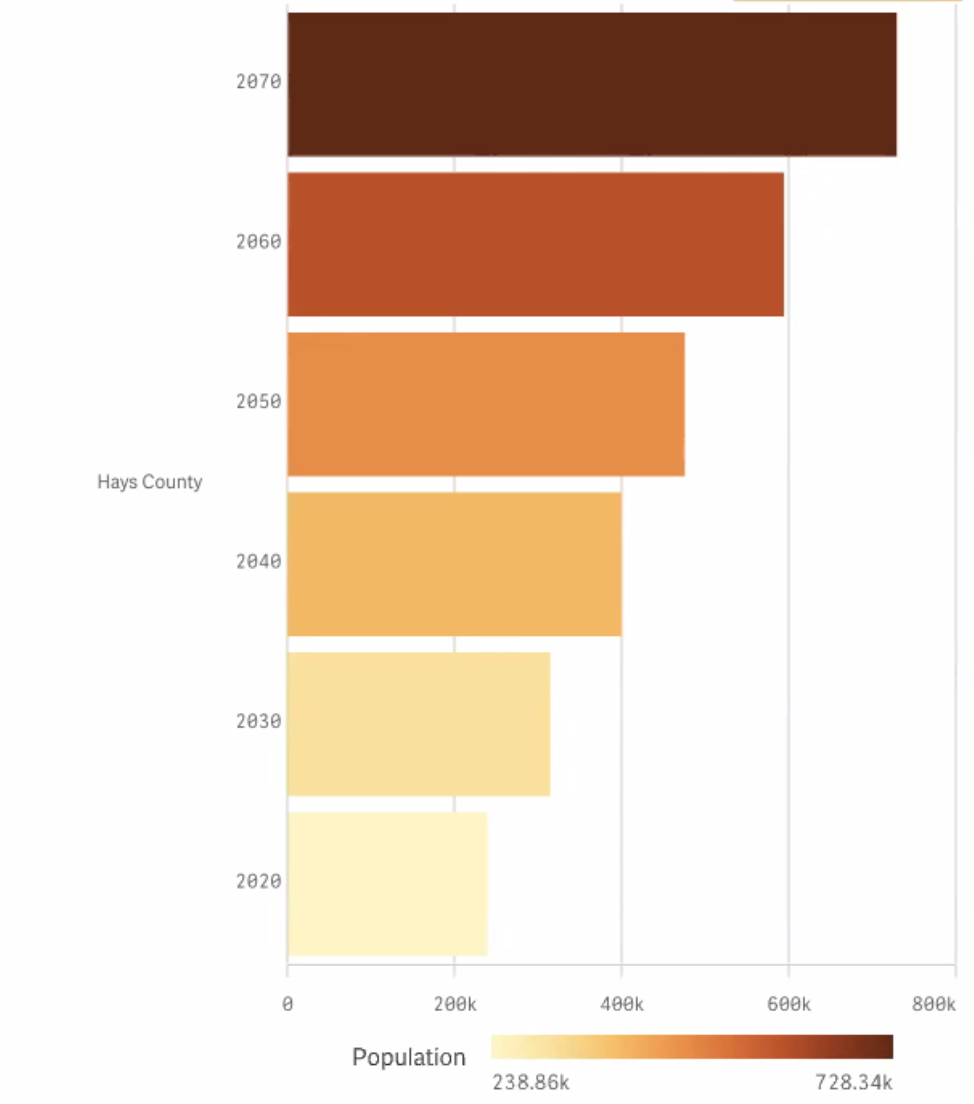

That rate of growth is almost double now. One of the epicenters is the Hill Country, where Austin and San Antonio are among the fastest growing cities in the nation. The population of Hill Country counties — 1.6 million in 1980 — now exceeds 4 million. And it got there a full decade earlier than demographers projected.

Larry McKinney of the Harte Research Institute has watched the upstream growth up close. He owns a home in Hays County that was surrounded by vistas and fields and is now hemmed in by 5,000-home subdivisions to the east and west. Dr. McKinney is also among the foremost experts in the life cycles of Gulf Coast estuaries, especially Corpus Christi Bay. Before assuming leadership of the Harte Institute 14 years ago, he spent a good chunk of his career at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, where he led work to determine how much fresh water was needed to keep the state’s important bays and estuaries healthy.

By 1994 his team had the numbers. Corpus Christi Bay, for instance, required 1.15 million acre-feet of fresh water to sustain healthy shorelines, shrimp and oyster nurseries, and an active sport fishery. Drainage from the western Hill Country into the Nueces River provided most of that water which, in the parlance of water regulators and hydrologists, is called “environmental flow.”

Keeping the bay healthy meant requiring upstream water users to conserve enough water to secure environmental flows to the Gulf. It required both hydrology and politics to achieve that goal. Upstream users were not inclined to use less water unless it was required — and Texans are notorious for disdaining rules and strictures.

The 57-year-old Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, though, is an agency with sufficient political muscle. The department oversees 10 major bays and estuaries, wildlife habitat and refuges, parks, sport fishing, commercial shrimping, and oyster harvesting along the state’s 367-mile Gulf Coast. Taken together, the agency’s oversight is closely tied to at least $5 billion in annual tourist and recreational income. The condition of the coast and the lifestyle it encourages accounts for billions of dollars more in residential and business development.

Even backed by the force of law, though, that directive has not succeeded in keeping enough water flowing to Corpus Christi and its bay, particularly in dry years.

The Texas Legislature took note of that economic fact when, prompted by drought and by legal skirmishes over water rights for environmental flows, it enacted statutes in 1997 and later in 2007. The statutes were meant to ensure that enough water arrived on the coast in periods of drought. The laws required that as upstream developers gained new water use permits, they didn’t consume every gallon. Theoretically, adequate water would flow to keep downstream natural areas, wetlands, wildlife refuges, and estuaries ecologically productive.

Even backed by the force of law, though, that directive has not succeeded in keeping enough water flowing to Corpus Christi and its bay, particularly in dry years. The theory behind the statutes was overwhelmed by the reality of water consumption in the Hill Country and across Texas. So much water had already been spoken for by permit and historic uses that not nearly enough was left in rivers and streams for environmental flows.

In the 2011 drought, the bay suffered as salt water from the Gulf intruded deep into its blue waters. Requirements for environmental flow were ignored. Zones of brackish water needed for sea life to breed and feed became too salty for them to survive.

“I came to the realization that this state is never going to get water for the environment,” said McKinney. “Instead what we have done in the state of Texas is basically downsizing our estuaries. We’re slowly cutting their scope and size.”

The Harte Research Institute and its colleagues in the city’s sport fishing community were not the only groups that took notice of how water scarcity made the bay sick. Administrators at City Hall and the Corpus Christi port also grew alarmed, but for a different reason.

The 2011 drought coincided with an oil and gas production boom in the Permian Basin. So much fossil energy was starting to flow from West Texas and southeast New Mexico that Corpus Christi joined Houston and Beaumont and other Texas coastal cities in pressing the White House and Congress to reverse a 1975 ban on domestic crude oil exports.

The Obama White House lifted the ban in 2015. Corpus Christi almost immediately became the locus of $54 billion in infrastructure investments – new and expanded refineries, tank farms, pipeline depots, natural gas processing plants, ethylene producers, export terminals, and a mammoth dredging project to widen and deepen the shipping channel.

Several installations have been completed. More are under construction. Even more than that are planned for completion after the pandemic subsides. Sections of shoreline of the Corpus Christi port are gigantic construction zones, a geography of towering cranes, swinging steel, squadrons of trucks and earth-moving equipment, and workers in lime safety vests. Corpus Christi emerged in January as the largest oil and natural gas export terminal in the United States, at times accounting for more than half of U.S. crude oil exports.

In April, though, as the pandemic swept the world and the transportation sector declined, exports began to retreat. At the start of the year Corpus Christi authorities thought their port had the potential to become as important to the global oil and gas trade as the Suez Canal or the Strait of Hormuz. The virus eliminated optimism underlying that projection.

Still, regardless of the effect of the virus on the energy trade, other installations under consideration and others being built near the port – a new $1.9 billion steel factory, a $16 billion liquid natural gas processing plant, and a $10 billion chemical plant — require water. Much more water than the 105,000 acre-feet that drains from Hill Country rivers into the Nueces, Guadalupe, and San Antonio that the port, other industries and businesses, and 500,000 metropolitan area residents now use each year.

Pumping from coastal aquifers is not considered an option because it can be dangerous. Up the coast, a warning emerged in Galveston Bay, where low-lying neighborhoods were inundated due to the practice of drawing water from the coastal aquifer, causing land to sink.

Given worsening water scarcity upstream, port and city administrators are anxious to diversify. Knowing that whatever decision they make will be expensive, Corpus Christi is considering an outside-the-box idea. They are looking to tap the bay or the Gulf and build two desalination plants to provide 94,000 acre-feet of water to industry.

In December, the City Council approved $450,000 for preparing and submitting state permit applications. The proposal has drawn some opposition from residents concerned about the multi-billion dollar cost of construction, the multi-million dollar annual cost of electricity and operation, and the unsolved dilemma of how to safely dispose of the millions of gallons of waste brine produced by big desalination plants. In April, the city applied for a $222 million loan to build the first plant from the State Water Implementation Fund for Texas, a low interest account administered by the State Water Development Board.

Mayor Joe McComb, a Republican who took office in 2017, supports using seawater as a source of fresh water. “If we’re going to continue to grow and create jobs and expand Corpus Christi, we have to have a dependable, uninterruptable water supply,” he told reporters.