Utilities Ordered To Forgive Customer Water Debt

Three cities are promoting the idea.

August 12, 2020

By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

CHICAGO — Englewood, on this city’s South Side, is one of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods. It is a district where the median household income of $20,991 is more than 60 percent lower than the city median.

Near its center is Action Coalition, a community group that serves as a lifeline for community members who bear the weight of desperate financial choices. The former parish house on Peoria Street where the coalition operates is where people in need sign up for local and federal aid programs that grant discounts on gas, electric, and water bills.

In a basement room where she assists clients, Ollie Raven, the coalition’s director, sketched the dilemmas that clients on low and fixed incomes face. “Which bill are you going to pay: taxes, mortgage, medicine?” said Raven in an interview with Circle of Blue. For three decades she has guided applicants through the process for federal energy bill assistance. “What is most important? Stay warm? You pay your gas bill. Need your water? Pay your water bill.”

On July 27, the Action Coalition began taking applications for a city program that provides low-income customers who are behind on their water bills with a path to wiping out their debt.

Clients recently have another option for financial relief, one that promises more than a discount. On July 27, the Action Coalition began taking applications for a city program that provides low-income customers who are behind on their water bills with a path to wiping out their debt. An initiative that Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced last November, the debt relief program is the first of its kind to be implemented for a large U.S. city.

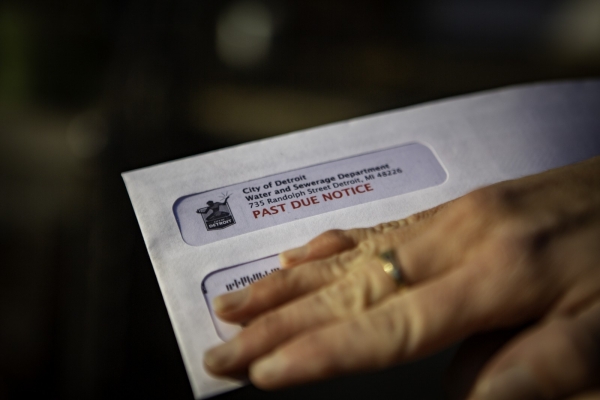

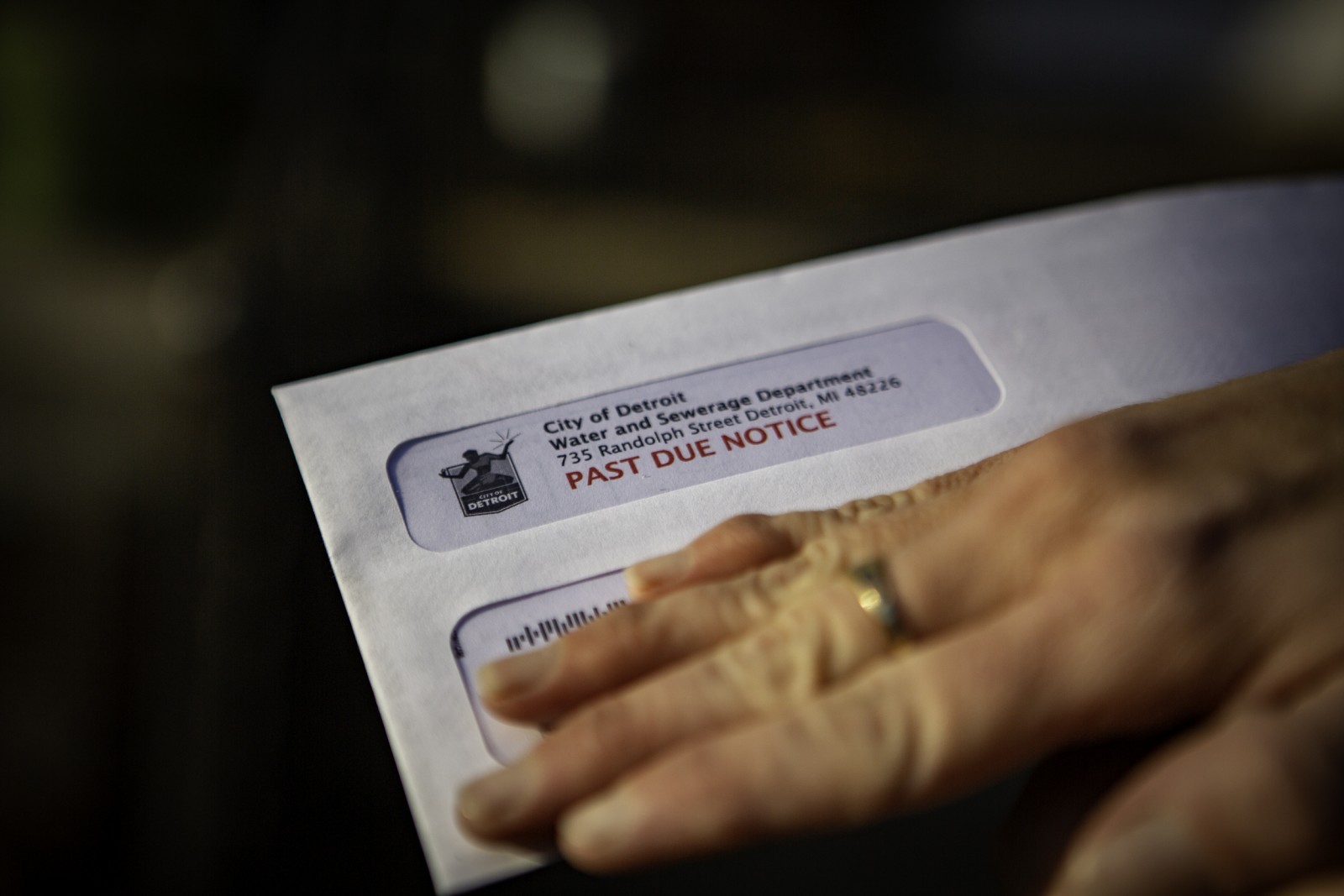

The need for such a program in Chicago is understandable. The department says that customer debt has soared nearly 300 percent since 2011, a rise that parallels a spike in the cost of water and sewer service. One in six residential water accounts was past due at the end of last year, according to data the department provided to Circle of Blue. At the end of 2019, residential customers owed the Water Management Department $341 million in unpaid bills.

“This program protects our residents, ensures access to basic human needs and builds on our commitment to reform our government toward ending systems that are punitive for those who can least afford it,” Lightfoot, a first-term Democrat, said at the program’s unveiling.

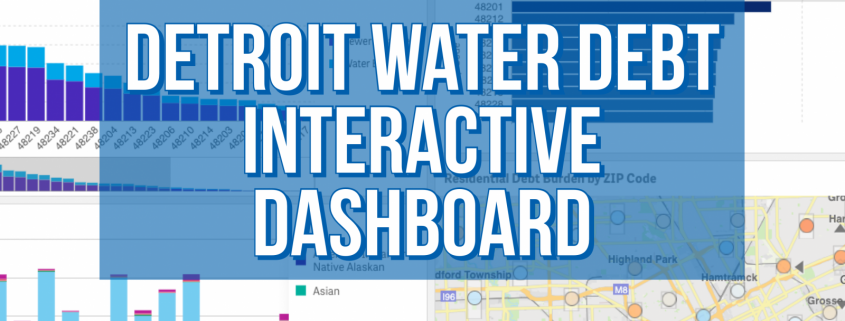

A Circle of Blue investigation found that more than 1.5 million households in a dozen large U.S. cities owe $1.1 billion to their water departments.

The Chicago initiative is a first attempt to address a problem that is growing too large to ignore in some of America’s metropolitan centers. A Circle of Blue investigation found that more than 1.5 million households in a dozen large U.S. cities owe $1.1 billion to their water departments. City leaders elsewhere have started to take note of the burdens. In addition to Chicago, city councils in Baltimore and Philadelphia passed legislation ordering their water departments to develop debt forgiveness programs, mimicking programs that some state regulatory commissions require for electric and gas corporations. Philadelphia’s program begins in September, while Baltimore’s might be delayed until July 2021 at the request of Mayor Bernard Young.

The Covid-19 pandemic, which is exposing the economic fragility of so many Americans, is quickening the national reckoning with water debt, in large part because more people are falling behind on payments. Though no nationwide numbers are available, utilities and aid agencies have noted an uptick in overdue bills and requests for assistance. Louisville Water, which serves Kentucky’s largest city, has seen the number of past-due accounts grow to 12,800 customers, up from an average of 2,000.

Regulators and lawmakers are starting to respond to the need. The Illinois Corporation Commission required three regulated water companies — Aqua Illinois, Illinois-American Water Company, and Utility Services of Illinois — to set aside funds for customer debt forgiveness. In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed a pandemic response bill in July that makes available $25 million to reimburse water utilities that cancel low-income customer debts. A maximum of $700 is available per customer and the debts must have accrued since March 1.

Advocates for debt relief say that these actions are necessary so that low-income residents can afford their water and not be buried by the fees, penalties, and service disconnections that are the aftershocks of overdue bills.

“We’re not asking for a free pass,” Rosazlia Grillier, a campaigner in Chicago, told Circle of Blue. “We just want the ability to be able to make things right.”

Rosazlia Grillier, co-chair emeritus with COFI POWER-PAC Illinois, an anti-poverty group, campaigned in her hometown of Chicago for debt relief and affordable bills. Grillier says that expenses such as water bills all add up for people struggling to make ends meet, especially during the pandemic. Photo © Alex Garcia / Circle of Blue

Rosazlia Grillier, co-chair emeritus with COFI POWER-PAC Illinois, an anti-poverty group, campaigned in her hometown of Chicago for debt relief and affordable bills. Grillier says that expenses such as water bills all add up for people struggling to make ends meet, especially during the pandemic. The city’s new assistance program will help to alleviate some of the crushing financial challenges that residents face by reducing bills and providing debt relief. Photo © Alex Garcia / Circle of Blue

‘A Great Start’

Grillier has been fighting for years to make things right for those in need. The relentless campaigner, who lives in the Englewood neighborhood, is co-chair emeritus with the community organizing group COFI POWER-PAC Illinois.

In 2018, POWER-PAC surveyed 304 parents across Illinois to understand the consequences of poverty in their lives. Three out of five respondents earned less than $15,000 a year. What the organization heard, Grillier said, is that debt, in all its forms, was holding people back. Student loans. Hospital bills. Car loans. Credit cards. Traffic tickets. One of the biggest sources of stress, especially for the poorest people, was utility bills.

“Even more than the bill itself were some of the fees that were attached to it that made a situation that was already challenging enough, almost impossible to navigate.”

“Even more than the bill itself were some of the fees that were attached to it that made a situation that was already challenging enough, almost impossible to navigate,” Grillier said.

Advocates had long sought to reform the collection of fees and accumulation of debt, but they had been stymied by a city bureaucracy that they claimed was too disconnected. Grillier said that changed in recent years, starting when former Mayor Rahm Emanuel appointed Anna Valencia as city clerk in December 2016.

From a rather obscure post in a first-floor corner of City Hall, Valencia started chipping away at the problem. She spearheaded a campaign in 2018 to reduce fees and debt around the city’s vehicle tax. “I couldn’t stay quiet, especially if I felt like we, as government, were placing barriers in people’s lives when we should be removing them,” Valencia told Circle of Blue. That test run led to a city-wide collaborative to reassess fines and fees across departments. Once Lightfoot was elected in April 2019, more doors that had been closed opened. Grillier stopped hearing, “No.” Conversations that had been ignored were now sent up the chain of command.

“I have lived in Chicago a very long time,” said Grillier, who was born in the city. “This sets a precedent of the first time I’ve seen departments come together to collaborate around these issues that have been very detrimental to some communities for a long time. So it’s a great start.”

The Utility Billing Relief program, as the city calls it, is open to homeowners who are at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line. Those who enroll receive a 50 percent discount on their water and sewer bill. Any previous debt is set aside and does not accumulate fees. After 12 months, if the customer has no overdue bills while on the reduced-payment program, the past debt will be eliminated.

The Chicago Finance Department estimated last fall that about 20,000 homeowners would be eligible for the program. With the pandemic, those numbers have probably increased, said Kristen Cabanban, a department spokesperson.

Raven said that people are calling Action Coalition of Englewood every day for more information about the billing relief program. Because of the pandemic, the coalition’s in-person services are temporarily closed, so all interactions are taking place over the phone. By its count, more than 200 people called in the first two days to inquire about the program.

Three major U.S. cities — Baltimore, Chicago, and Philadelphia — have implemented or are developing programs to help low-income residents eliminate their water debt. Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Delayed Implementation

Taking debt relief from concept to implementation has not come so quickly in other places.

The Philadelphia City Council passed landmark legislation in 2015 that required the water department to develop a water-billing system based on income. With certain exceptions, households making less than 150 percent of the federal poverty line are eligible. Their water bill is set at between 2 and 4 percent of their income. The income-based billing program, called TAP, opened for enrollment in July 2017.

“Even in the most stable neighborhood in my district, water is a challenge and water payments were a challenge.”

The bill’s sponsor was Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, a four-term City Council member, who witnessed debt burdens among her constituents. She represents a tenth of the city’s population, but her district carried 20 percent of the water debt. “Even in the most stable neighborhood in my district, water is a challenge and water payments were a challenge,” Quiñones-Sánchez told Circle of Blue.

The income-based program is a reversal from the department’s past practice toward customer water debt, which bordered on indifference, according to Robert Ballenger, an attorney at Community Legal Services of Philadelphia who acts as a public advocate in water rate cases.

“There was no meaningful effort to stop the accumulation of this debt over a period of years and years and years,” Ballenger told Circle of Blue. “And it continued to build and it accumulated primarily in low-income neighborhoods with high concentrations of people of color.”

“There was no meaningful effort to stop the accumulation of this debt over a period of years and years and years. And it continued to build and it accumulated primarily in low-income neighborhoods with high concentrations of people of color.” – Robert Ballenger

The Philadelphia Water Department declined to be interviewed for this story.

The legislation that established income-based payments included a stipulation to address this indifference. The law ordered the water department to develop rules for “earned forgiveness” — meaning that the department would provide customers an opportunity to eliminate not just the fees on their account but also wipe away the principal on their debt.

Developing those rules took some time, but the process is meant to be user-friendly. Customers enrolled in the income-based payment program will automatically be enrolled in the debt forgiveness plan. After 24 full monthly payments, starting in September, the debt will be cleared. If customers miss a payment, they do not go back to square one. Their 24-payment counter is paused and begins again after a full payment.

The Philadelphia Department of Revenue notes that the 13,701 customers who enrolled in TAP in 2019 had a combined water debt of $39.7 million.

A similarly belabored rule-writing process is unfolding in Baltimore. The City Council in November passed legislation that requires the Department of Public Works to establish an income-based billing system, forgive customer debt, and have clearer procedures for resolving billing disputes.

The legislation’s provisions were supposed to be implemented this month, but Mayor Bernard Young requested that the council extend the deadline to July 2021. Young also signed an executive order on July 8 that blocks the law from going into effect until after the Covid-19 emergency has ended.

“The mayor’s administration and the Department of Public Works have dragged their feet and failed to make affordable, accountable water service a priority,” said Rianna Eckel, the Maryland organizer for Food and Water Watch, which has been active in advocating for water affordability legislation in the city.

The Baltimore Department of Public Works declined to be interviewed for this story, and Mayor Young’s office did not respond to phone and email messages.

As in Chicago and Philadelphia, there is a need. Baltimore’s water prices more than doubled in the last decade, and the city is committed under a federal consent decree to spend $1.6 billion by 2030 to control sewage overflows and leaks.

Inside the Chicago Avenue Pumping Station which draws water from Lake Michigan through the Jardine Water Purification Plant. Photo © Alex Garcia / Circle of Blue

Debt Write-Offs

Customers are just one side of the debt coin. On the other side is the utility, to whom payment is owed. What happens when utilities do not receive those payments? They have their own way of dealing with the loss.

Utilities know that, even in the best of times, not every customer will pay every bill in full. Historically these bad debts have been quite low, between 0.5 percent and 2 percent of billed revenue, according to estimates from several utility analysts.

When customers are late with payments, utilities believe that speed is essential in trying to recover payment. The longer a bill is past due, the less likely a utility will receive the money. In Atlanta, the collection rate for bills that are 90 days past due is about 80 percent. The rate plummets to about 20 percent after 120 days.

“Over 180 days, we have to allow that none will be collected,” Mohamed Balla, deputy commissioner of finance for the Atlanta Department of Watershed Management, told Circle of Blue.

What happens next depends on the city. How utilities handle bad debt is determined by state and local accounting laws. “There are as many ways as there are utilities,” Harold Smith of Raftelis, a consultancy, told Circle of Blue.

In essence, though, utilities will clear the bad debt from their books. That happens either formally, through a write-off, or informally, through an allowance.

Balla explained the process in Atlanta. The first distinction is whether the debt is active or inactive. Active debts are those accounts that are still receiving service. By city code, they cannot be written off. Inactive accounts — maybe the homeowner died or moved away – can be written off after a year as long as the utility has tried to collect it.

Inactive accounts can be a substantial portion of a utility’s customer debts. Balla reckoned that about 30 to 35 percent of Atlanta’s customer debts were inactive. In Chicago, just more than half of the $341 million in past-due residential balances was considered inactive.

For active accounts, instead of a write-off the city will take what is called an “allowance.” It’s an admission that the debt is uncollectable but without officially wiping it off the books. These accounting treatments give the utility a clearer sense of its expected income and where to set rates in the future.

Write-offs and adjustments are one-sided, though. The utility clears the debt from its accounts, but the burden — of fees, property liens, and other penalties — still clings to the customer.

“It’s still on the household’s books,” Balla said. The goal of the debt relief campaigners is to extend that clean slate to the customers as well.

Filtration basins at Jardine Purification Plant catch any remaining particles before the water is sent through the distribution system. Maintaining and repairing the pipes and treatment facilities that supply drinking water is not cheap. Infrastructure costs are one reason that water rates are increasing nationwide. Photo © Alex Garcia / Circle of Blue

Filtration basins at Jardine Purification Plant catch any remaining particles before the water is sent through the distribution system. Maintaining and repairing the pipes and treatment facilities that supply drinking water is not cheap. Infrastructure costs are one reason that water rates are increasing nationwide. Photo © Alex Garcia / Circle of Blue

Debt, Fines, and Fees

Water debt relief is marching in parallel with a broader movement that is reexamining municipal fines and fees. City leaders from coast to coast are reviewing the equity and fairness of their parking ticket charges, court filing costs, library fines, and traffic violations. They are responding to research showing that fines and fees, as currently structured, generate mistrust and erect barriers to public services that are most impenetrable for poor and minority residents.

Unaddressed and unfettered, this financial discrimination can be part of a combustible mix. The Department of Justice investigated the Ferguson Police Department in the wake of protests that followed the police shooting of Michael Brown, a Black man, in August 2014. The DOJ report concluded that the police and municipal court in Ferguson focused on revenue rather than on public safety. Instead of protecting residents, those institutions were pilfering them.

In the utility world, water departments are a laggard on these issues of affordable billing and debt relief. That is due in part to the fact that for many years water bills were much cheaper than energy bills. Congress established an energy bill assistance program in 1981, but no federal aid is available for water.

“The municipal court does not act as a neutral arbiter of the law or a check on unlawful police conduct,” the report states. “Instead, the court primarily uses its judicial authority as the means to compel the payment of fines and fees that advance the City’s financial interests.”

The findings in that report reverberated far beyond the St. Louis suburbs. Inspired by the Ferguson case and the work of local activists, the San Francisco Treasurer’s Office, in 2016, established the Financial Justice Project. The project works with city and county departments to review the effect of their fines and fees on poor and minority people.

“When you charge fines and fees beyond the ability to pay, it hits people very hard,” Anne Stuhldreher, the director of the Financial Justice Project, told Circle of Blue. So hard, in fact, that many cannot pay and will have trouble standing up again, she said. What was happening in San Francisco mirrored the findings of Grillier’s POWER-PAC survey in Illinois. “The debt is not going to come in as revenue, but it’s going to hang over families and drag them down.”

The Financial Justice Project worked with the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission to review its water service fees. The commission ended up discarding a $55 fee that was charged when water was shut off and then again when it was turned back on.

“For somebody who is unable to pay, that is a burden. It puts them in a bad financial situation,” Diala Batshoun, the commission’s customer service operations manager, told Circle of Blue.

In the utility world, water departments are a laggard on these issues of affordable billing and debt relief. That is due in part to the fact that for many years water bills were much cheaper than energy bills. Congress established an energy bill assistance program in 1981, but no federal aid is available for water.

Amid the Covid-19 financial disruption, Congress is once again debating a federal aid for low-income customers. In lieu of a federal program, water utilities could look to electric and gas utilities for a blueprint on how to handle customers with huge debt loads. Debt forgiveness programs for water utilities “are almost nonexistent,” said Charlie Harak, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center. But power companies have run these sorts of programs for decades.

The difference is due to governing structure, explained Harak, who works on energy utility debt forgiveness programs. Most energy providers are publicly traded companies that are regulated by a state commission. Most water providers, by contrast, are public entities. Their main oversight is City Council or citizen boards.

“It’s easier to move regulatory policy on behalf of low-income residents via state commission,” Harak told Circle of Blue.

California, for instance, has a constitutional amendment — Prop 218 — that, in effect, prohibits municipal water utilities from using ratepayer revenue to fund a customer assistance program. On the other hand, the private water companies that operate in the state are regulated by the Public Utilities Commission and are required to have an aid program for low-income residents.

Harak said that about ten states, mostly in the Northeast and Midwest, plus California, have debt relief requirements for at least some regulated energy companies. Of those, Harak completed a detailed review of forgiveness programs run by energy utilities in Massachusetts. He concluded that the programs were “a major success.”

Among the benefits of a debt forgiveness program, Harak found that it fosters a positive relationship between the customer and the utility. Customers enrolled in the program pay some amount, instead of nothing at all. For the utility, it reduces the cost of collecting unpaid bills and shutting off service to those who are behind. Automatically enrolling all eligible customers expanded the reach of the programs, but resulted in a lower percentage of people completing all the requirements, perhaps because not all those who were automatically enrolled were motivated to follow through.

The model that energy utilities use is similar to the programs that Chicago and Philadelphia have outlined for water. Take, for example, New Start, a debt forgiveness program operated by Eversource Energy, an electric and gas provider that operates in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

To enroll in New Start, an Eversource customer must have a debt that is $100 or greater and is 60 days or more past due. Household income must be at or below 60 percent of the state median. Eversource then calculates a discounted monthly bill based on past energy use. After each on-time monthly payment, one-twelfth of the debt is eliminated. The customer, assuming all goes well, is cleared of their debt to the utility.

All usually does go well, said Mitch Gross, a spokesperson. The company started the program on its own more than two decades ago and reviews it with its regulators. About 13,600 customers in Connecticut and 6,300 in Massachusetts are enrolled.

“Absolutely, yes, it’s a benefit to us,” Gross told Circle of Blue. “The last thing we want to do is to disconnect for nonpayment.”

Photography:

Alex Garcia

J. Carl Ganter

Data Visualizations:

Claire Kurnick

Joe Warbington – Vizlib

Reporting for this article was supported in part by the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Stay informed about global WaterNews and never miss any of Circle of Blue’s award-winning reporting by joining our weekly newsletter.

Have new, international water news delivered to you daily by signing up for Circle of Blue’s The Stream.

Signup for the Federal Water Tap, Brett Walton’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton