After Plumbing Code Setback, Georgia Health Officials Refocus Legionella Prevention Effort

New working group mulls regulatory options for dealing with America’s deadliest waterborne disease.

Georgia health officials are looking for ways to incorporate Legionella prevention into existing regulatory processes.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

It’s back to the drawing board for the Georgia Department of Public Health as health officials seek to develop rules to prevent the growth in building plumbing of bacteria that cause a deadly lung infection.

A state task force last year rejected the health department’s proposal to add requirements to the state plumbing code to combat Legionella bacteria.

The plumbing code amendment that the department proposed would have incorporated an industry standard for reducing the risk of Legionnaires’ disease. The pneumonia-like illness — America’s deadliest waterborne disease — is caused by inhaling Legionella bacteria. Those bacteria flourish in the pipe networks that deliver water within hospitals, hotels, and conference halls. The standard has been incorporated, in part or in full, into regulations issued by New York state and federal healthcare agencies.

Minimizing the risk of Legionnaires’ disease is increasingly urgent as the number of cases nationally climbs to new highs nearly every year. Last August, after the task force had made its decision to reject the plumbing code amendment, Georgia experienced the largest Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in state history. The outbreak — with 14 confirmed cases, 67 suspected cases, and one death — was linked to cooling towers at the Sheraton Atlanta Hotel.

Following the plumbing code task force’s rejection, the Department of Public Health regrouped and convened its own working group to study the issue further.

The goal of the working group is to collaborate with industry representatives and local officials to find potential ways of reducing Legionnaires’ disease risk through code revisions.

Which Code Should Be the Target?

During their first meeting, held November 22, 2019, working group members and Department of Public Health staff debated new lines of attack.

Meeting minutes were obtained by Circle of Blue through a public records request. They show the department searching for the best way to harmonize Legionella-prevention rules with current regulatory processes.

The Department of Public Health did not allow staff members who organized the working group to be interviewed. The department also would not comment on any of the group’s activities.

“This work around strategies for Legionella prevention in Georgia is ongoing, and we are not at a point where we have information ready to be discussed or released outside of the working group,” Nancy Nydam, the department’s director of communications, wrote in an email to Circle of Blue. Attempts to contact individual staff members were redirected to the communications department.

One thing is clear: the Department of Public Health wants new requirements to fit into established codes and procedures. It does not want to erect a new regulatory apparatus.

“We prefer to incorporate Legionella rules and regulations into existing processes rather than generate novel processes (e.g. public health permitting for cooling towers), but those are still options that should be considered,” the minutes state.

Attendees suggested other options beyond the plumbing code. An unnamed member mentioned the fire code, which has requirements that apply after a building is occupied. That is a potential entry point for Legionella prevention.

People who work on Legionella issues have told Circle of Blue that building owners generally do not act to reduce the risk of disease transmission unless they are required to do so.

Building plumbing systems can be designed so that bacteria have fewer places to grow — Legionella multiply in stagnant water found in dead-end pipes — but maintaining proper water temperatures and disinfectant levels are preventative best-practices for building managers after construction. The meeting minutes mention determining minimum standards for building design and implementation.

The minutes note that the working group will look into other codes — building and property maintenance, for example — as potential vehicles for Legionella rules.

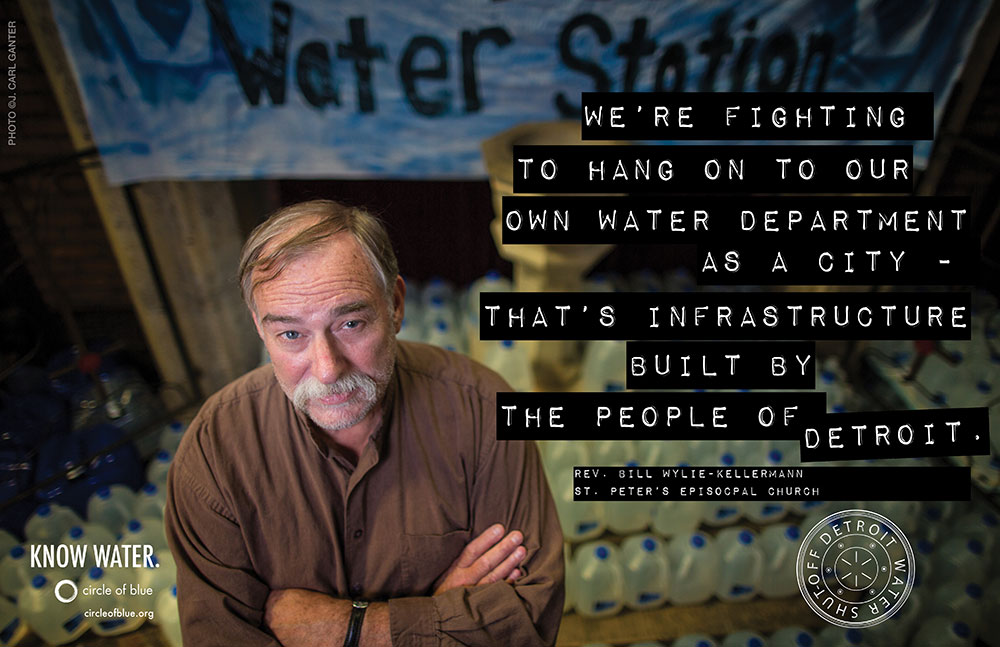

Pam Burnett is the executive director of the Georgia Association of Water Professionals, a group that provides educational services to water utilities.

Burnett, one of three people on both the plumbing code task force and the working group, said that the Department of Public Health learned a lesson during the plumbing code revision. She said that Legionnaires’ disease was a new issue for most task force members, who did not know enough about the illness and its causes to feel comfortable enacting rules to address it.

The Department of Public Health “realized in that process that there were multiple potential partners and players in addressing the risks and we all needed more education,” Burnett told Circle of Blue. “We couldn’t move forward on something that we didn’t understand.”

Burnett said it’s still too soon to know what the working group’s outcome will be. Just coming together to discuss the topic is a minor success, she argued.

“We don’t know where it’s going,” Burnett said. “But the nice thing is we’ve never had all these people in the same room before talking about the same topic but with a different set of eyes.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!