As Pandemic Amplifies Financial Stress for Water Utilities and Customers, North Carolina Governor Announces Financial Aid

State-ordered shutoff protections have expired, customer debt is rising, and some utilities face revenue shortfalls. Tens of millions of dollars in financial aid has been approved, but it may take weeks to arrive.

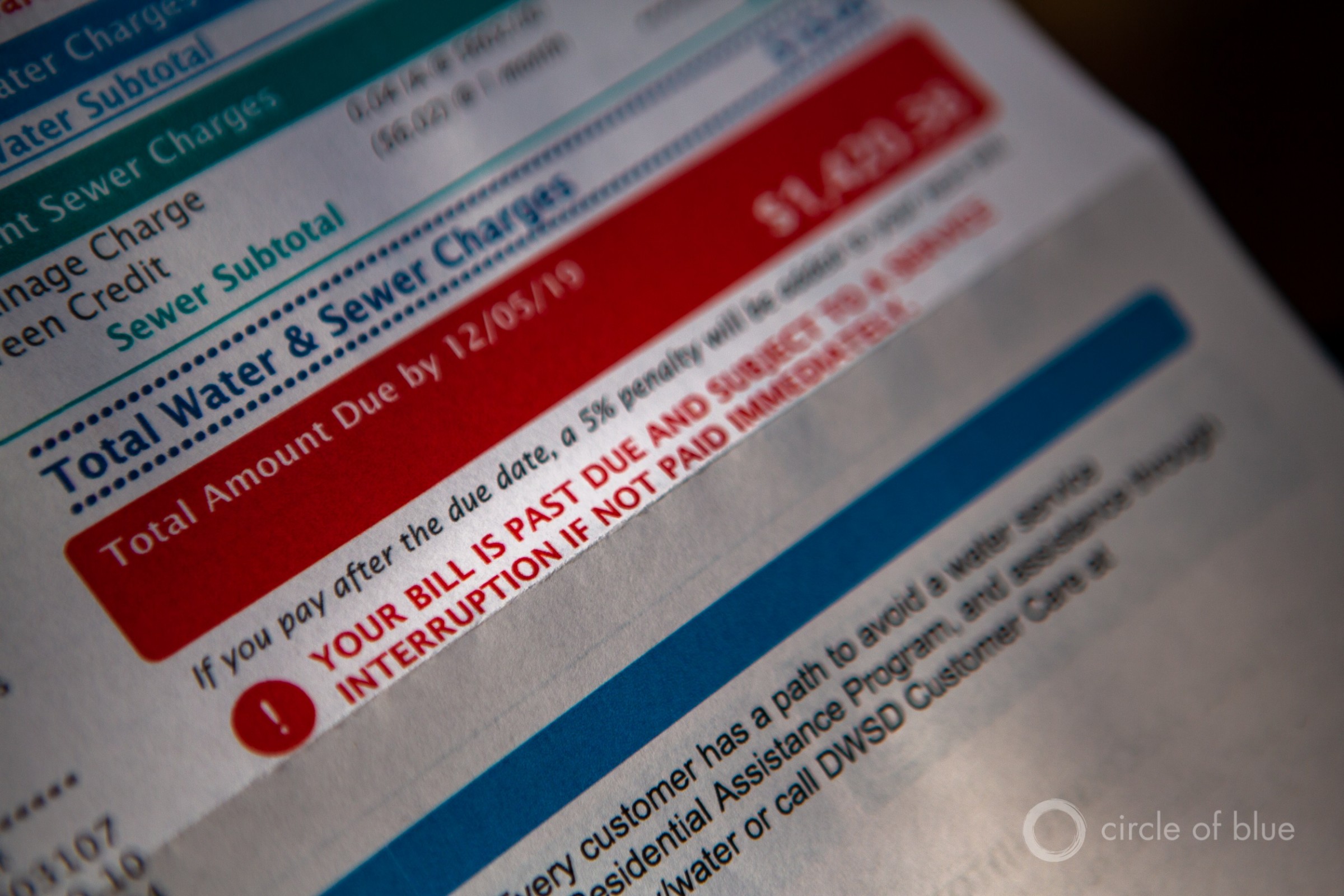

A resident of Detroit displays a past-due water bill. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Nearly six months into the pandemic in North Carolina, the financial consequences for water utilities and their customers are becoming clearer.

The pain, researchers have found, is not evenly distributed. A few more people are behind on their water bills. But those who are behind are much deeper in debt.

The same range of outcomes is true for water utilities, too. Some have the cash reserves to weather a 10 percent decrease in revenue caused by business closures or late payments. Others will make do in a downturn by cutting costs. They will do less maintenance and trim capital spending. But a few utilities — no more than a handful, says Shadi Eskaf of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — face a “near-immediate financial collapse” and could go bankrupt in the next few months without intervention.

Those are some of the main findings from a report by the Environmental Finance Center that Eskaf co-authored. Based on data from 84 utilities, the number of households that are behind on water bills at the end of July rose by 17 to 29 percent compared to the same period last year.

At the same time, the size of past-due balances has climbed at a much higher rate. Arrears for 89 utilities reporting data were 42 percent higher at the end of July, compared to the same period last year. For some utilities, 40 percent or more of their customers are behind on their bills. In other words, those who are struggling, are struggling more.

“We have that really wide range,” Eskaf told Circle of Blue. “We know that some [utilities] were struggling with collections and payments before Covid, and Covid exacerbated those conditions.”

In response, Gov. Roy Cooper announced on August 25 a $175 million financial assistance package for renters, local governments, and utility customers who are behind on payments. The assistance package is cobbled together from various federal funds, including those that Congress made available in the CARES Act.

The governor’s aid package is divided into several pots of money. About $94 million will go to individuals to help with rent and utility payments — not just water bills, but also gas and electric. The money will be distributed to individuals through community agencies via the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency (NCORR).

“NCORR knows the need is pressing and we are working to finalize the program as quickly as possible,” Bridget Munger, a spokesperson, wrote to Circle of Blue in an email. “Federal funding has a regulatory process that must be followed, so it is going to take additional time to get the program opened for applications. We expect that to happen in the coming weeks.”

The program will target low- and middle-income households whose economic hardship is linked to the pandemic, Munger said.

An additional $28 million goes to small local governments — municipalities under 50,000 residents and counties under 200,000 residents. They can use the money as they wish but the state is encouraging them to direct some toward rent and utility assistance.

The Environmental Finance Center found that total past-due water utility balances in the state, including those that accrued before the pandemic began, are between $61 million and $81 million. Total customer past-due balances for all utilities that reported data to the state — electric, gas, and water combined — amounted to $273 million at the end of July.

Though state agencies are working to set up the aid programs, residents and local governments might not receive any money until mid-October, according to Al Ripley, director of consumer, housing, and energy affairs for North Carolina Justice Center, an advocacy group.

Ripley has been tracking how the state’s pandemic response affects renters and utility customers. He said that there are a number of intermediate steps before money from the governor’s aid package can be distributed: federal rules for spending the funds need to be finalized, agreements with local agencies have to be signed, and eligible residents must be identified and submit applications. That adds several weeks to the response time.

“What are we going to do in the meantime?” Ripley asked.

State-Mandated Customer Protections Ending

The North Carolina Justice Center and other advocates are concerned that the governor’s financial aid package is not large enough to address the problem. They propose $400 million — from CARES Act funding or the state rainy day fund — to eliminate water, gas, and electric past-due balances and stabilize utility finances.

At the federal level, House Democrats included $1.5 billion for water-bill assistance in a pandemic relief measure they passed in May, but the Senate has yet to act.

Ripley said he sees a “patchwork dynamic” taking shape in North Carolina, where a resident’s location and utility providers determine the options that are available.

What does that patchwork look like? Consider water service. Most of the state’s residents are served by municipal providers, which are subject to the governor’s executive orders. A much smaller portion are customers of investor-owned utilities, which are regulated by the North Carolina Utilities Commission.

The governor ordered municipal providers to halt shutoffs starting on March 31. The North Carolina Utilities Commission put its moratorium in place on March 19.

The governor’s shutoff moratorium expired on July 29, though it requires utilities to provide customers with debt repayment plans that extend for at least six months. The commission, meanwhile, was more deferential toward customers. It allowed investor-owned utilities to disconnect non-paying customers beginning September 1. But it is requiring utilities to offer 12-month repayment terms, double the period required of municipal providers.

Utilities can be more lenient, if they want. Raleigh Water, a municipal provider that serves the capital region, is not disconnecting water service and is allowing customers to repay past-due balances over 12 months, according to Aaron Brower, the assistant director. The continuation of its shutoff moratorium is because of changes that it would need to make to its billing system in order to comply with other provisions in the governor’s order, Brower told Circle of Blue.

In its July 29 decision to lift the shutoff moratorium, the commissioners expressed concern about the financial viability of utilities, if bills continue to go unpaid. “The growing unpaid charges could potentially, contrary to the public interest, place continuation of utility service in some areas in jeopardy,” they wrote.

Which utilities will be most affected by revenue losses? “That’s the question of the hour,” Elsemarie Mullins, a project manager at the Environmental Finance Center and a report co-author, told Circle of Blue.

There are so many factors at play, Mullins said. How long are the repayment plans? How much of the customer debt can be recovered? Is there a change in usage patterns, such as a large factory shutting down? Does the utility have a large residential customer base? Utilities that rely more on residential use for their revenue are less likely to be affected, she said.

Raleigh Water has seen its past-due balances rise from about $3.5 million before the pandemic to $7.5 million today. “To date, it’s fairly manageable,” Brower said.

Shutoffs might prod payment from those who are taking advantage of lenient rules. But for customers in severe financial stress — those who are out of work and no longer receiving more expansive unemployment payments of $600 per week that expired at the end of July — a shutoff can worsen an already precarious situation.

“We are very concerned that in order for people to defend against Covid, they need access to utilities and a place to live,” Ripley told Circle of Blue.

Without stabilization there could be long-term effects, Mullins said. Especially for smaller utilities, which already are sailing into stiff economic headwinds. Financial pressure today — whether it’s revenue declines or inability to raise rates because of a local recession — could led to regional mergers down the road with neighbors on firming fiscal footing, an option that the state is encouraging struggling utilities to consider.

“It might be a couple years before someone has to consider a regionalization project, and part of that could be because they couldn’t raise their rates in 2020,” Mullins explained. “Those sorts of effects will take a lot of time to work out and probably won’t be able to be traced back only to Covid-19.”

This story has been updated with information from Raleigh Water.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!