As Water Backs Up, an Asset in Michigan Becomes a Liability

A drainage dispute roils Jackson County’s prized attraction and its operation.

Photo provided by Elaine Wolf-Baker

By Hannah Ni’Shuilleabhain, Circle of Blue

Elaine Wolf-Baker remembers a childhood spent ice skating on the frozen pond in Sparks Foundation County Park, a landmark in Jackson County. She grew up here, amid the lake-dappled landscape of southern Michigan, and on clear winter days she would course up and down the park’s lagoons and connected streams for miles.

“This is the iconic park for our county,” Wolf-Baker told Circle of Blue. “I used to live in San Francisco: this is the Golden Gate Park.”

Wolf-Baker’s fond nostalgia contrasts with her current mood. Cracks — both literal and figurative — are appearing in Jackson County’s prized attraction and in its operation.

From her home next to the park, Wolf-Baker has become attuned to environmental changes around her in the past few years. She sees stagnant water in the lagoons, which encourages algae growth. Wildlife has declined. Below ground, there are more problems. She claims that faults in the park’s drainage system are causing water to back up into homes, including hers.

It didn’t have to be this way. The park was an early example of integrating natural landscapes into urban systems. But when environmentally conscious designs were neglected, problems emerged: ecological instability, expensive cleanup bills, and weakening of nearby infrastructure. The park could be a champion for the county, helping to ease the transition to a wetter climate future. Instead, it is mired in accusations of mismanagement.

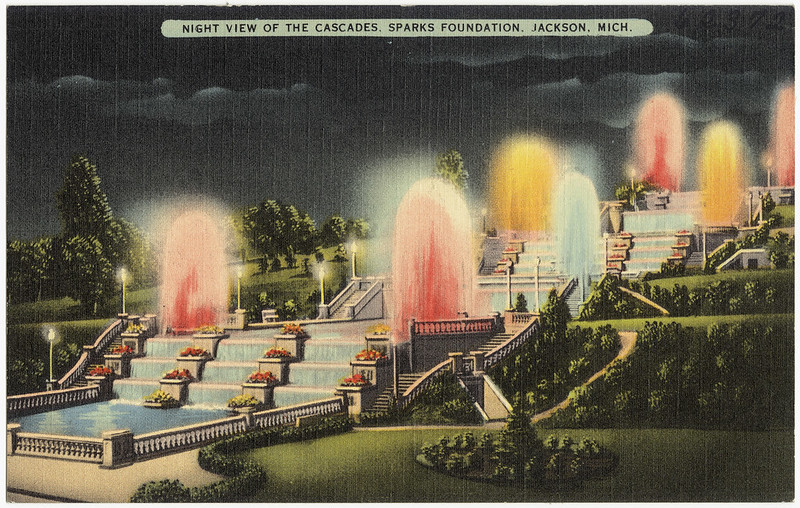

Postcard dated 1930-1945. Photo provided by Flickr Creative Commons, Boston Public Library Print Department

The Making of an Attraction

A public park located in southwest Jackson County, Sparks Foundation County Park, also called Cascades Park, once was “swampy bog land” according to its website. In 1929, residents William and Matilda Sparks founded an organization to transform the 465 acres into a private recreational space.

”It was this genius design, it was way ahead of its time,” said Wolf-Baker, a member of the Michigan chapter of the Sierra Club, who has been researching the park’s history for over two years. “They took this boggy area and dug this lagoon out there.”

Along with lagoons, the initial design consisted of a handful of recreational amenities: a golf course, canal, clubhouse, picnic areas, and landscaped grounds. The main attraction, though, was the illuminated Cascade Falls, a concrete staircase made of six fountains and 16 waterfalls that are lit up during summer nights.

The park had a more utilitarian purpose, too. Engineers incorporated the lagoons into the county’s drainage system. They functioned as a stormwater retention pond. Runoff from the surrounding area would supply the lagoons and the original water features before trickling into the Grand River watershed by way of the Kibby drain.

It was an early practice of what urban planners now call “green infrastructure,” or water management systems that follow natural hydrological processes to reduce polluted water runoff and minimize flooding. Constructed wetlands, a type of green infrastructure, can be a cheaper complement to centralized stormwater treatment facilities.

Water runoff management is a necessity for any town with flooding concerns, a description that will apply to more and more of Michigan in the coming years. According to a 2016 release by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency titled “What Climate Change Means for Michigan,” the state will see more rain and stronger storms as the planet warms. An abundance of water all at once with nowhere to go could be a disaster for residents’ homes and health.

Basement Flooding

When Wolf-Baker speaks to walkers on the popular trail surrounding the park or engages with people through her Facebook page, she uses environmental concerns to make a connection. For most, the remembered beauty of the wetland is common ground.

Wolf-Baker’s motivation for action is even more personal. She’s been living in her parent’s home since 2013, a home she estimates is about a hundred feet from the lagoon. The sliver of land the home sits on is the lowest area next to the park. “Because they don’t have a drain anymore, the drain is my basement,” Wolf-Baker said, referring to the alleged flaws in the drainage system.

Since her first day living there, Wolf-Baker noticed the wetness of the basement and the cracking of the floors. Time exacerbated the problem. “Water comes up through cracks, comes down the wall, flows through the drain, through a pump outside, runs outside to make a pond in the middle of the road. It works day and night, every minute, from fall rain season to July.”

Wolf-Baker knows 12 homeowners in her neighborhood who are experiencing similar leakages. Although the effects of a high groundwater table are only visible in a small number of homes now, Wolf-Baker believes the problem, if left unresolved, could threaten several city blocks.

Photo provided by Elaine Wolf-Baker.

Design Flaws

After William Sparks’ death, ownership of the park was transferred to the Jackson County Parks Department. Although the park is run by the county, the county drain commissioner had no jurisdiction over it. Wolf-Baker believes the park’s drainage problems arose under the county’s ownership.

In 1994, the Parks Department dug an on-site well specifically for use in the park’s water features. This well pumps a little under 12 million gallons of freshwater a year from the deep Marshall Sands aquifer. While the well water used for the Cascades runs in a closed, looped system, the lagoons continue to receive storm runoff. Although it means the sources are disconnected, the effects overlap to create current problems.

Deterioration of the Cascade Falls structure resulted in water loss from the looped system, as reported in a 2012 systems analysis. With the waterfall and surrounding pools now fed largely by groundwater, the lagoons are receiving more stormwater than originally intended. An abundance of stormwater in one location may soak through the soil zone to recharge groundwater and raise the shallow aquifer, possibly to the land surface. Normally the lagoon’s water would run to its surface-water body through the drainage system, but an additional intrusion inhibits that option: an outlet cutoff.

Wolf-Baker estimates between 1992 and 2000, during restoration of the park facilities, city workers impeded the outlet of the lagoon under Cascade Manor, a banquet hall and wedding venue. This outlet drains the water from the park water attractions, through a stream in the Cascade Park Golf Course and into the Kibby drain, which connects to the Grand River watershed. The county and drain commissioner contend that the outlet is still satisfactory; Wolf-Baker disagrees.

“They put a little pipe, about the size of a very large pizza pan,” Wolf-Baker said. “What I found out is that they put up a plate over the end of the pipe, so a little tiny bit might go through.”

This plate was a cheaper alternative to dredging the pond of sediment buildup, which would cost the county millions of dollars. By raising the water level of the lagoons, algae would be covered for the benefit of the view from the Cascade Manor. And control of the water flowing through the stream in the Cascade Park Golf Course meant less issue of upkeep for the golf course. “They threw a bunch of dirt over there so the golf carts could go over it,” Wolf-Baker said, claiming there were three or four places where the stream was purposely plugged along the course.

This 36-inch plate was brought to the attention of the Jackson County Board of Commissioners in 2019. The drain commissioner determined from pictures shared by a former Cascades Golf grounds superintendent that a plate was placed in front of the entry to the tunnel in 1989.

Wolf-Baker thinks the first plug could have been ignorance of the initial design plan. But if the actions taken to plug the water drainage are true, it could be considered illegal.

Monica Day was a candidate for Jackson County drain commissioner in the recent election, losing to incumbent Geoffrey Snyder.

“Drainage is examining how to manage economical factors and pollution to the environment,” said Day. She describes drainage as a complex practice of competing priorities: good drainage protects residents’ health by preventing water contamination and infrastructure damage such as mold. On the other hand, drainage can be costly to maintain and difficult to control the flow around protected wetlands.

Day mentioned the natural flow doctrine in a detailed Facebook post about the park. “A downstream landowner may not modify their property in such a way as to flood out uphill neighbors. The downstream landowner must allow water to flow across their property.” She believes this was violated when instead of digging out the accumulated sediment plugging the water, impediments were placed. It’s an instance “when [the county] refuses to do what they’re entrusted to do,” Day said.

A successfully managed runoff wetland isn’t too far from Jackson. Tollgate Wetlands in Lansing, like Cascades Park, was built to receive stormwater runoff from the surrounding area. When the pond came to the same point of needing major dredging of built-up sediment, the community added a string of small ponds to the design. The smaller ponds allowed sediments to settle out before they could reach the largest pond. This area is praised for its current beauty in ways Wolf-Baker would reminisce about the Cascades of the past.

Day has spoken with Wolf-Baker about her drainage concerns. Besides weakening infrastructure, Day is most concerned by public health effects of rising groundwater, such as the asthma Wolf-Baker connects to the black mold in her basement.

Various agencies are pointing fingers, but Day thinks that shifting the blame is simply evading responsibility. Although the County Board of Commissioners approved a recommendation to remove the plate that is impeding drainage, it could not immediately follow through on the action without a permit from the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) due to the park’s designation as a wetland. The county has not yet requested this permit.

The problem continues to fester. Millions of gallons of stormwater and freshwater now sit on the surface with less room to move. “You think of a bathtub, and the water is plugged up. It can’t go anywhere anymore,” Wolf-Baker said.

Photo provided by Elaine Wolf-Baker.

A Study on the Table

Wolf-Baker petitioned county commissioners for two years and submitted public comments asking for the impediments to be removed and the county to acknowledge their negligence, but she received lackluster responses or none at all. This year matters have turned in her favor. Snyder, the county drain commissioner, met with EGLE in January about the obstructed stream on the golf course, and concluded a canal was dug in violation and thus requires a downstream impact study before proceeding with the plate removal.

In May, Jackson City Council members adopted a resolution requesting that the Jackson County Drain Commission take responsibility for the park. The resolution asks for the establishment of a county drain consisting of the lagoon system and outlet channel of the Cascades Park, meaning the entire apparatus would fall under drain commissioner jurisdiction.

After completing a preliminary lagoon study over the summer, the Jackson County Parks Department requested a motion in September for the general government committee to approve a water influence study for Sparks Foundation County Park. The request mentions the problems that Wolf-Baker has kept track of: flooding in the neighborhood adjacent to the park, nutrient pollution, and an almost stagnant flow in the lagoons. The County approved the request in October, with the total cost of the study split between the County Parks Department and City of Jackson. The project is projected to conclude April 2021.

In an email to Circle of Blue, Snyder said he does not have a role in the matter as there is no established drain or easement under his jurisdiction related to the park. So far, his involvement includes describing the facts he’s observed in a change of water surface elevation from the time of construction to today. In case the county’s hydrology study results in a petition, the commissioner will need to acquire permits from EGLE before project design and construction begins. EGLE also requires a study to see how interfering with the current drainage flow would impact those living downstream and the protections granted to the area as a wetland, but Wolf-Baker suspects most of those requirements will be met in the county’s study.

Wolf-Baker is pessimistic of what will be said after the study. “They don’t want anybody to come after them for ruining their houses, so what they’re planning on doing instead is to say the flooding is natural because we’ve got more rain, so we can’t fix it,” she said. “It’s never going to dry up, just going to get bigger and nastier.”

Wolf-Baker connects it to economic interest: the park is a big attraction for the area. “They put enough money in there to keep it looking nice, and they just ignored draining.” And impeding the water flow means fewer expenses at a time when the county is trying to raise funds to replace the Cascades’ outdated electrical and mechanical components and repair the aging amphitheater. “It’s cheaper to put dams than dredge,” said Day.

This fall, the flooding seemed to stop. But rather than a certain end, Wolf-Baker believes it’s a temporary consequence of the Cascades’ water pump breaking in June. The long-term forecast is no better. Predicted precipitation trends for Michigan won’t be forgiving to faulty drainage systems.

Hannah Ni’Shuilleabhain is a student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and completing her Journalism Residency at Circle of Blue. She has reported for her college radio WNUR and online magazine NorthByNorthwestern on campus events, Evanston-Chicago news and scientific research. Based in her hometown Plano, Texas, her interests include rowing and learning Turkish.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!