Congress Adds $638 Million in Water-Bill Debt Relief to Coronavirus Package

Funds will cancel water debt or lower rates for low-income households. But questions remain about how the funds will be distributed for the first-ever federal water-bill assistance program.

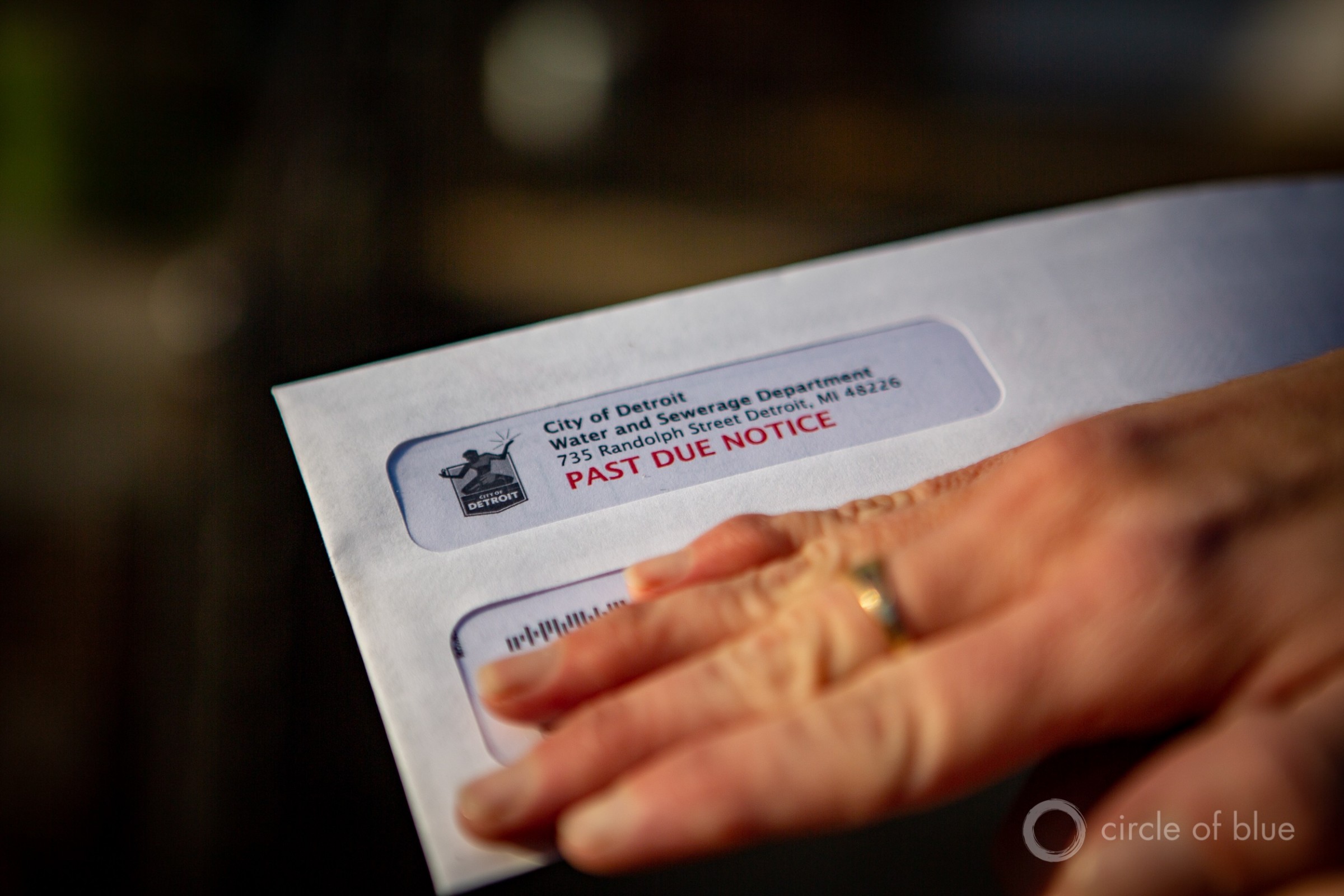

Overdue water bills have soared during the pandemic as people lost jobs and utilities stopped shutting off water for late payment. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

People who are behind on their water and sewer bills because of the pandemic will be getting some help from Congress.

Federal lawmakers wrapped up their work before the holidays, tying together a $900 billion coronavirus relief bill, a $1.4 trillion budget outlay, and several policy measures. Included in the package that the House and Senate approved on Monday evening is $638 million to forgive overdue water and sewer bills.

The funding is intended to help low-income families in financial distress because of the pandemic. But the legislation does not include a prohibition on shutting off water service during the national health emergency, a provision that Democrats offered in earlier proposals but one that was opposed by utility groups.

Though the legislative work is complete, there are questions not only about how the program will be rolled out, but whether it is large enough to address the problem.

“I am doubtful if this amount of [money] would cover all of the water utility debt in California, much less the U.S.,” Greg Pierce wrote to Circle of Blue in an email. Pierce researches water access and affordability as the associate director of the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

A Circle of Blue investigation earlier this year in a dozen large cities found sizable debts, even before the Covid-19 pandemic. Based on data from public records requests, some 1.5 million residential accounts in those cities owed $1.1 billion to their water departments.

The final assistance sum of $638 million is significantly lower than the $1.5 billion that House Democrats had sought this spring.

How will the program be carried out? According to the legislation, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will send money to states and tribes, which will, in turn, distribute the funds to utilities. Utilities have the option of reducing customer arrears or reducing water rates for eligible customers.

Funding will be awarded to states and tribes based on two criteria: the percent of households with income less than 150 percent of the federal poverty line and the number of households paying more than 30 percent of income on housing.

Utilities are supposed to use existing processes, programs, and procedures to identify people in need of funding.

Pierce said that the distribution of the funds will be the hard part, and potentially the biggest drawback to the approach that Congress selected. Once money is disbursed to the states and tribes, how will they decide which of the country’s roughly 50,000 community water systems takes priority?

There is little direction in the legislation as to how utilities use the funds, other than targeting people with the lowest incomes. How will utilities handle outreach to these customers? Pierce wonders. Will utilities require them to apply for relief, or will utilities choose for themselves?

Tommy Holmes, the legislative director for the American Water Works Association, a water industry group, said that inclusion of water-debt assistance was something of a surprise. Though utility groups had been advocating for relief, they did not know the funding would be in the package until they saw the text on Monday.

Holmes also is uncertain about how the funds will be distributed.

“I don’t know how states will decide how to distribute funds,” Holmes wrote to Circle of Blue. “I don’t know if utilities will have to apply or if there is existing data, such as poverty levels at the local level, that will determine distribution of funds. However, my impression all along has been that any assistance program like this would have to be pegged to specific customer accounts at the local level. HHS might use as a template the LIHEAP program for low-income citizens who need help paying their energy bills. Hopefully, we’ll all know more as we unpack this 5,000+-page bill and HHS has time to lay out the program.”

Dan Harnett, who handles legislative and regulatory affairs for the Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies, viewed the assistance as a “positive development.” It’s the first time that Congress has set aside money for assisting with water bills.

But given that there will be more need than available funding, Harnett said that states, tribes, and utilities will have to make choices about who receives money and who doesn’t.

“This is a good opportunity to give it a test run,” Harnett wrote to Circle of Blue. “Hopefully the 50 states will develop best practices for effectively screening applicants and awarding funds, and this experience can be used to inform creation of a permanent program.”

Evidence from other cities indicates that water-bill debts have grown since March, when governments started shutting down segments of the economy to prevent the spread of the virus.

For WSSC Water, a water and wastewater utility in Maryland, the pandemic caused past-due balances to “skyrocket,” said Karyn Riley, WSSC intergovernmental relations director. Customer debt grew from $36.2 million in March to $65.4 million in November.

Tucson Water, which serves Arizona’s second-largest city, has seen past-due balances grow from $3 million in March to $8 million in December. “It has steadily climbed over the last eight months,” said Silvia Amparano, the deputy director.

Tucson has allocated $500,000 for water bill assistance to low-income residents. Half of a household’s debt will be forgiven if the customer agrees to a 12-month repayment plan for the remaining balance.

The cities of Los Angeles and Louisville provided customer debt relief from funding in a $2.2 trillion pandemic relief bill that Congress passed in late March. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services allocated $20 million from its CARES Act funding to 116 utilities statewide.

The new agreement, however, does not include additional such aid to state and local governments.

The original headline of this story has been corrected. The bill provides $638 million for debt relief, not $683 million as was initially stated.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!