Country’s Aging Dams, a ‘Sitting Duck,’ Facing a Barrage of Hazards

Repairing all the country’s deficient dams could cost $70 billion. Having them fail would come with a far greater price, experts say.

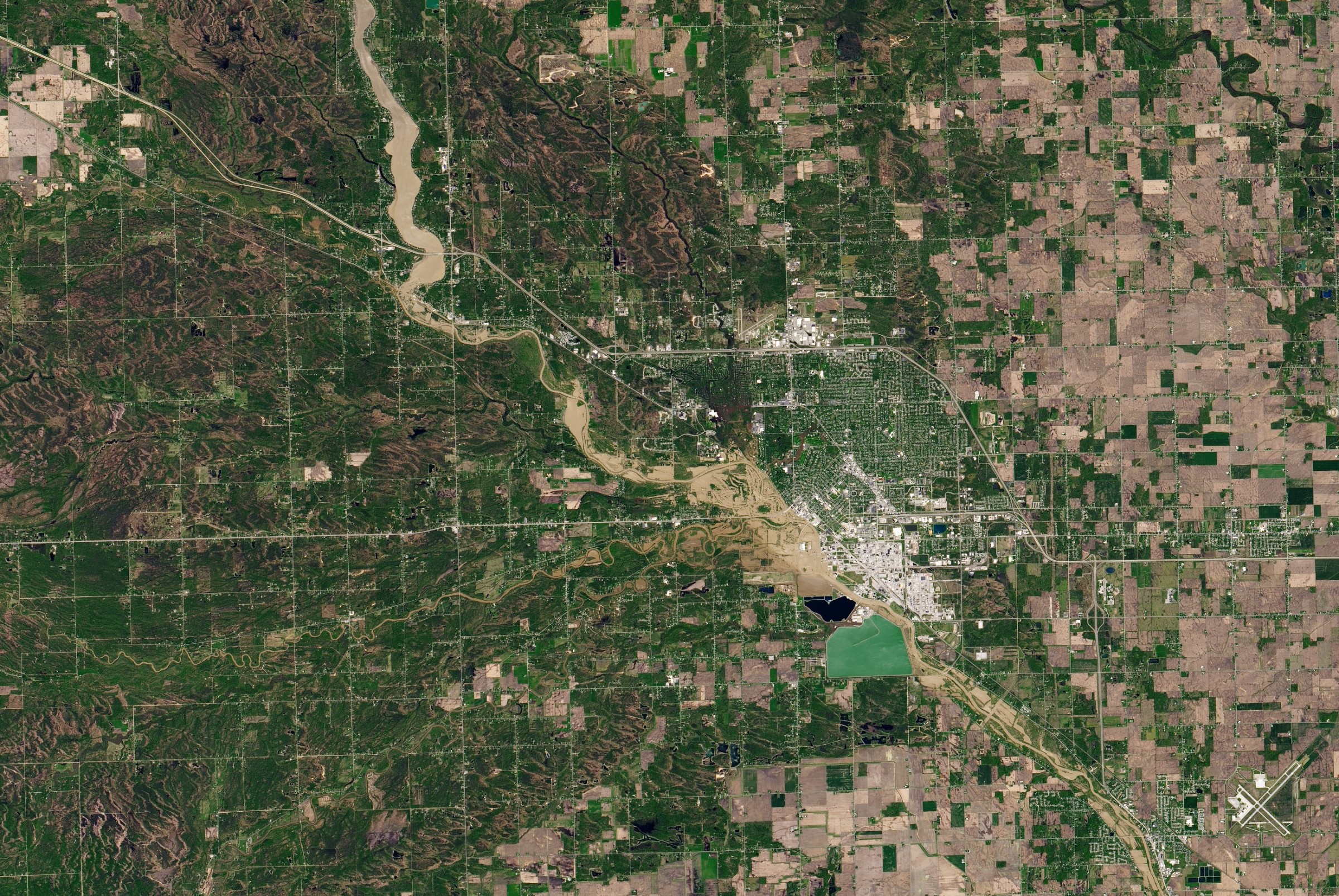

Aerial view of flooding in Midland, Michigan, on May 20, 2020, following the failure of Edenville and Sanford dams. Photo via U.S. Geological Survey Landsat 8

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Edenville Dam, the barrier across the Tittabawassee River in Gladwin County, Michigan, that failed this week, was completed in 1925, a greybeard among the state’s dams.

The mid-section of the 54-foot-high, privately-owned structure, whose original purpose was to control floods, gave way on Tuesday evening during heavy rains. Water from the breach rushed downstream, crippling in the process the smaller Sanford Dam, also built in 1925. Set free, the Tittabawassee River spread across the city of Midland, setting a record-high flood peak. Some 10,000 people fled the unexpected deluge.

Or was it unexpected? Perhaps not, say dam experts. At least not when considering the broader picture.

Edenville is the latest alarm bell that is ringing over the condition of the country’s 91,457 dams. In March 2019, Spencer Dam in northern Nebraska, failed following a severe bomb cyclone storm and the breakup of ice on the Niobrara River that interfered with its operation. In February 2017, the main spillway at Oroville Dam, the tallest dam in California, cracked and eroded spectacularly, leading to evacuation orders for about 188,000 people downstream. In 2015 and 2016, tropical storms that swept across the Carolinas resulted in dozens of collapsed dams that cast flood waters far and wide. Before those events, there were warnings. A 2012 presentation from a Maryland dam safety official was titled “Dodging the Bullet.”

Edenville is the latest alarm bell that is ringing over the condition of the country’s 91,457 dams.

The average age of the country’s dam fleet is 57 years, according to the National Inventory of Dams, a database run by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In Michigan, the average is a bit older: 74 years. Many dams are at retirement age and their upkeep is generally neglected or given cursory attention, said Upmanu Lall, a professor of engineering and director of the Columbia Water Center. So it is with so many of the country’s roadways, power stations, and water delivery systems. The assets of yesterday have become the debts of the present — and for dams, those debts are a growing liability.

“We have a ridiculous number of these dams that are not in a satisfactory state,” Lall told Circle of Blue. “They should probably be removed, which would make the environmental groups happy. But it costs money to remove them. It costs money to monitor them, and neither of those things is happening. So they are essentially sitting ducks. When a large enough rainfall event happens, with or without climate change, the dam goes. And that’s what happened in Michigan now.”

Martin McCann is the director of the National Performance of Dams Program at Stanford University. McCann thought that the Oroville failure was a wakeup call for an industry that had mobilized to reduce risk following a string of deadly dam disasters in the 1970s, but had grown complacent after years of relative calm.

“We have a ridiculous number of these dams that are not in a satisfactory state,” Upmanu Lall, a professor of engineering and director of the Columbia Water Center.

Oroville should have changed that, he said. California’s dam safety program was considered the best in the country: well-funded with professional staff who were experienced and technically competent. But even that was not enough to prevent a near calamity at Oroville, a dam owned by the California Department of Water Resources.

“What Oroville told us was: good may not be very good at all,” McCann told Circle of Blue, referring to the perceived quality of a dam safety program. “Or, being the best may not be very good at all, which leaves everybody else that much further behind.”

McCann agreed with the conclusions of an independent review of the Oroville incident: that California’s dam oversight suffered from systemic failures. That conclusion could be applied nationwide, he said.

Engineers and regulators have much to keep their attention. Climate change is the risk that is front of mind. A warming atmosphere holds more moisture, which is leading to larger storms. Between 5 and 8 inches of rain fell across central Michigan in the three days before Edenville Dam failed. The National Weather Service estimated the probability of such rainfall occurring in a year at 0.5 percent.

More severe floods could produce a “greater risk of infrastructure failure in some regions,” according to the federal government’s fourth National Climate Assessment, which was published in November 2018.

But, as Lall points out, climate change is not the only risk factor. The rainstorm in Michigan was rare but not outside the bounds of what was historically possible. Urbanization is another consideration. Cities have grown up around dams. More hard surfaces — parking lots, roof tops, roadways — increases runoff into rivers and lifts the height of floods. Dams might not have been designed for this additional stress, especially if silt has reduced their storage capacity or, as in Oroville’s case, if their design is flawed.

“Things will get worse,” Lall said, referring to the effects of climate change. “But even if they don’t get worse the situation is bad.”

High Hazards, Low Funds

Edenville Dam was completed in 1925 and classified as a high hazard. Its owner, Boyce Hydro Power, lost its federal license in 2018 to generate hydropower at the dam. Regulators at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, which did a visual inspection of the dam in October 2018, say they were concerned that the spillways were inadequate for handling a large flood.

High-hazard is a classification given to any dam whose failure could cause a loss of life downstream. An Associated Press investigation last year found that 1,688 of the country’s high-hazard dams were rated in poor or unsatisfactory condition. That is an undercount since six states did not provide ratings for their dams, claiming security concerns. Others do not have the funds to rate the condition of all their dams.

The cost for repairing all the country’s dams: more than $70 billion.

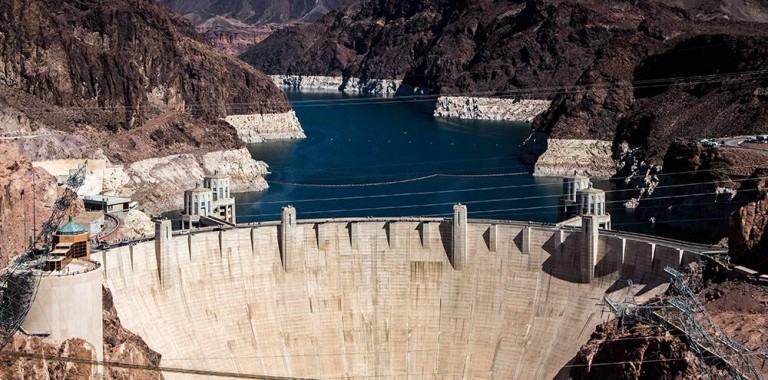

The federal government controls many of the largest dams, like Hoover and Glen Canyon on the Colorado River. But federal dams, comparatively well managed, are in the minority. They account for only 4 percent of the country’s total. The majority of dams, some 63 percent, are privately owned. The rest are managed by public utilities, states, and local governments. States regulate these structures, which tend to be smaller than the federal behemoths. Oversight and funding for their inspection and maintenance varies widely.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency recently launched a program to provide federal funding for safety improvements at dams operated by state and private entities. The grant program was authorized by Congress in 2016.

The sums appropriated for this program — $10 million in fiscal year 2020 — are a pittance compared to the scale of the problem. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates the cost of upgrading non-federal, high-hazard dams to be $20.4 billion. The cost for repairing all the country’s dams: more than $70 billion.

In general, are the resources put toward the problem of risky, high-hazard dams sufficient to address it?

“I think you have to say no, pretty categorically,” McCann said.

The financial risk of dam failures is largely unmapped in the United States.

And yet, the costs of inaction are clear: evacuation orders in the middle of the night, risk of death, flooded homes, damaged property, and enormous recovery bills. The price tag for repairing Oroville Dam’s busted spillway is now above $1.1 billion.

Lall noted in a report for the Global Risk Institute that the financial risk of dam failures is largely unmapped in the United States. Such an accounting would include the infrastructure assets at risk as well as property damage.

Tearing down dams that have outlived their benefits and become an environmental or public safety burden is one option. American Rivers, a conservation group, counts 1,722 dams removed in the United States between 1912 and 2019. Most of the removals have taken place in the last two decades, but they are constrained by the amount of available funding.

Money, McCann said, is the great facilitator. But so is leadership. He said a paradigm shift is needed in the industry: more resources, better training, more state involvement.

The bottom line, Lall argued is that “we’re just ignoring these problems.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!