Covid-19 Outbreaks In Prisons Underscore Need For Reform

Unsanitary conditions and secrecy contribute to the spread of disease, experts say.

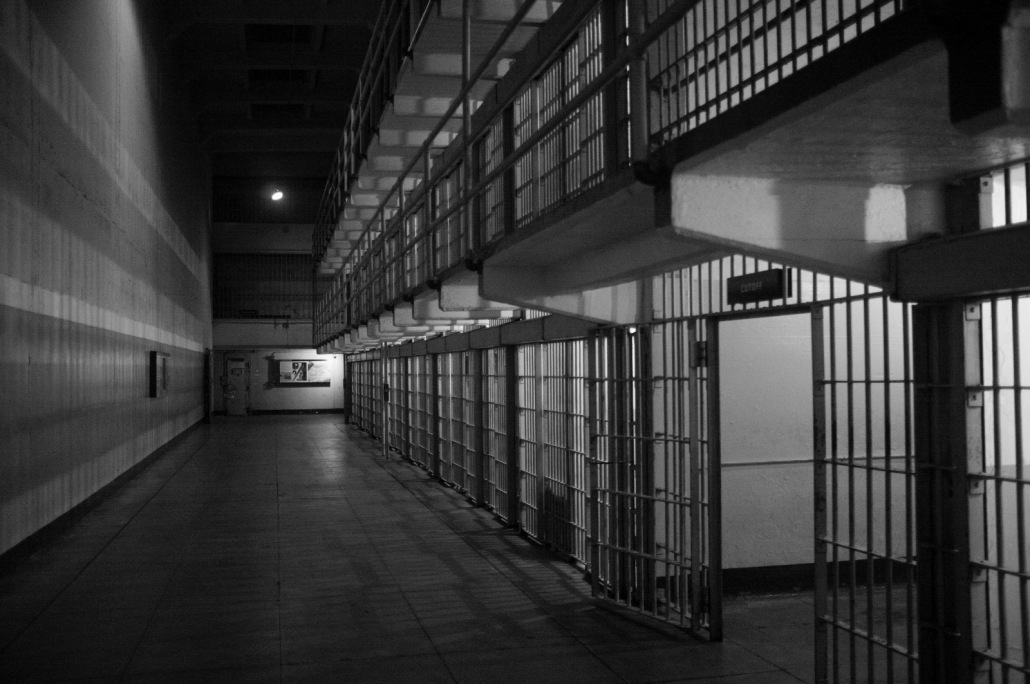

The coronavirus pandemic is highlighting longstanding sanitation issues in prisons. © Emiliano Bar/Unsplash

By Jane Johnston, Circle of Blue

The U.S. prison system has emerged as a center of Covid-19 transmission. Along with other national virus hot spots — meatpacking facilities, farmworker housing, and nursing homes — the outbreaks in jails and detention centers highlight a constellation of disease risks for people on the margins of American society.

“The pandemic has driven home the lessons that how these facilities are designed really matters,” Michele Deitch, a distinguished senior lecturer at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas, told Circle of Blue. “The fact that people can’t physically separate from each other, the fact that they are so densely populated, the fact that people in custody don’t have ready access to hygiene supplies and a supply of water, all of those are things that have contributed to the high, high spread of the disease, the massive spread of disease, and the high numbers of deaths.”

As of August 18, according to data collected by the Marshall Project, over 102,000 cases have been confirmed among U.S. prisoners, and just over 22,000 cases among prison staff.

Aside from being densely populated and housing a high number of at-risk people, such as the elderly or those with chronic illnesses, prisons are generally unsanitary. Deitch said that prisoners often lack hygiene necessities like soap or hand sanitizer. Some don’t even have consistent access to running water.

“All the recommendations that the experts are telling us on the outside that we need to take are measures that really are not available to people inside,” said Deitch, who has spent her career trying to improve conditions for prisoners.

There are many reasons for the spread of Covid-19 in prisons, Deitch explained. Policy decisions, like not releasing medically vulnerable people or transferring people between facilities, contribute to crowding and disease spread. So does the failure to take basic precautions, such as not wearing masks or not quarantining prisoners with confirmed or suspected cases. A federal judge ordered California prison officials in July to dedicate space in each state jail for quarantine.

Keri Blakinger, who covers the U.S. criminal justice system as an investigative reporter for the Marshall Project, knows the difficulty of attributing an illness acquired in prison to a specific cause. With so many risk factors, it’s hard to draw a direct line between lack of water access and the spread of the virus.

“If there’s any kind of disease outbreak, it’s really easy to point to all these other factors that can contribute,” Blakinger told Circle of Blue. But that doesn’t mean that it’s not important to be concerned about water access, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in prisons, she added.

WASH services have long been a source of health trouble inside prisons, contributing to disease outbreaks. “We can just sort of look at these things and logically understand that they’re problematic,” Blakinger said. “But the nature of prisons makes it really hard to prove specific examples of causality.”

One of the reasons for this is that reports from prisoners of water outages, sewage backups, and other plumbing problems often contradict what administrators say. “It’s just really difficult to verify because they’re behind prison walls,” she said. “It’s really hard to get any kind of proof.”

Preparing for Simultaneous Hazards

Chronic problems like infrastructure maintenance in jails tend to be magnified in times of crisis. Hurricane Harvey, in 2017, flooded three state and three federal prisons in Beaumont, Texas. Drinking water was disrupted for days and some inmates complained of dehydration.

Melissa Surette (Savilonis), adjunct professor at Endicott College and emergency management professional who has spent ten years studying how U.S. prisons respond to disasters, says that such stories indicate a lack of emergency planning.

The vast majority of prisons are underprepared for hazards like natural disasters and disease outbreaks, she found. The reason? Correctional facilities are underfunded.

With consistent line-item funding, prisons could fix big issues like staff shortages, purchasing and upgrading equipment, and planning for disasters.

“These are challenges we see across the country with other types of facilities as well, not just prison systems, but it’s really critical that we focus our time and effort on funding prison systems so they can plan and prepare for disasters,” Surette said.

As the country enters peak hurricane season — the Gulf Coast now faces Hurricane Laura, a Category 4 storm — Surette said there are two types of disaster plans that prisons should have in place. One is an operational plan, or what they’ll do when the storm strikes. The other is a mitigation plan, which Surette said is critical for identifying risks and developing strategies to address them before the disaster occurs.

Risks could include being located in a flood-prone area or one that is exposed to extreme wind or storm events.

Still, those plans mean nothing if a prison doesn’t have the resources or staff to support them.

“So you can have a wonderful plan that details how you’re going to respond and recover from an incident,” Surette said. “But if you don’t have the staff that know what’s in the plan, or what to do, or they if they don’t have access to it, and then if they don’t have the resources to support that plan, that presents a lot of challenges, and you kind of have this cascading effect.”

Blakinger said the real problem isn’t a lack of staff. It’s that there are too many prisoners. About 1.5 million people in the U.S. are incarcerated, meaning for every 100,000 Americans, 431 are imprisoned.

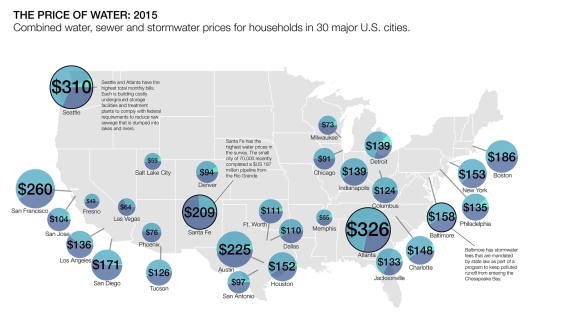

“I think that these sort of really basic maintenance problems are going to exist as long as we are trying to incarcerate this many people,” she said. “Mass incarceration is expensive and we don’t have money for the upkeep and that shows when it comes to these plumbing issues.”

The pandemic could be the nudge that catalyzes difficult debates. Sick prisoners have highlighted the need to re-examine not just operating procedures, but basic assumptions about the U.S. criminal justice system, whether it means providing more funding or locking up fewer people.

“We shouldn’t just be Covid-focused,” Surette said. “We should be thinking about this from a holistic perspective.”

Jane is a Communications Associate for Circle of Blue. She writes The Stream and has covered domestic and international water issues for Circle of Blue. She is a recent graduate of Grand Valley State University, where she studied Multimedia Journalism and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies. During her time at Grand Valley, she was the host of the Community Service Learning Center podcast Be the Change. Currently based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Jane enjoys listening to music, reading and spending time outdoors.

COVID-19 has entered United States prison systems at alarming rates. Disparities in social and structural determinants of health disproportionately affect those experiencing incarceration.