By Hannah Ni’Shuilleabhain, Circle of Blue

Photographs by Brian Lehmann for Circle of Blue

MARFA, TEXAS (December 14, 2020) — Marfa is small. The population of the artsy tourist stop in West Texas is just over 1,500. Its reputation — anchored by the legacy of artist Donald Judd — looms larger than its capita. But even as that reputation grows, the population is declining. Real estate prices reflect the curation of luxury in the middle of nowhere, and push out locals who can’t afford the rising cost of living.

A short drive outside of Marfa is the even smaller community of Valentine. A town of under 200, it only gains recognition for its Prada storefront, an isolated art piece now most seen as an Instagram background. But most of the land around Valentine is used for ranching, raising cattle and horses on flat plains that touch the horizon.

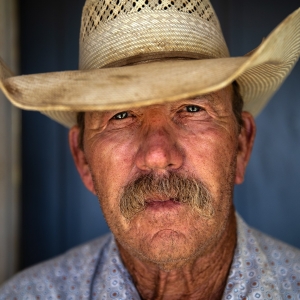

Bodie Means, 68, is embedded in the cattle-rearing ways of West Texas. “I’ve been here all my life,” said Means. He spends his day sorting cattle and team roping calves with a group of four or five locals. This afternoon he’s working with Marcelo Urias and Chuy Navarrete. “When we get off work [is] when we kind of turn loose,” said Means.

Means, like a lot of rural people in the country’s drylands, always has one issue in mind: drought. He knows when the rain needs to fall: “Our rain generally comes in — maybe some in June, then July. July to September is our rain season,” Means said.

This year, it didn’t rain like he wanted. “It didn’t rain in a lot of country in Texas, like a lot of country,” Means said. All of the Southwest was in some form of drought this past rainy season, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Central and West Texas were in exceptional drought, and in the Big Bend region rainfall was six to eight inches less than normal from June to August. Prolonged dry periods can have a devastating effect on the herd, and thus, the livelihood of many residents.

Drinking water isn’t an issue for the herd; well water is dependable for that. The bigger problem is the grassland that the cattle graze. Lack of rain can decimate the forage. Means has to consider the relationship between the number of cattle to the amount of grass on the estimated 70,000-acre range. “Where we live you have to take real good care of your country because of this very reason: it can not rain and you’ll still have some form to eat if you watch how many [cattle] are running on the country.”

West Texans are resigned to a certain cycle of drought. “We’ve been through this too much the last 20 years,” Means said. “Starting in the nineties we had to get rid of nearly everything we had. Then it kind of started back like it was gonna get better, and it actually had.” Texas has experienced historic swings from severe drought to plentiful rain, but since 2010 the region has experienced declining conditions that echo the seven-year dry spell that ravaged the region in the 1950s. The destruction of thousands of farms and ranches in the state is an unwanted recurrence.

After a season of drought, Means knows his only option is to sell his head of cattle. “We had some beef cow, we’ve already cut them down,” he said. “We may have to get rid of more just because of the droughts. Those particular cattle we were doing that day,” — here Means is referring to the cattle shown above — “I’ll probably have to get rid of those cows some time in January.”

Now nearing winter, Means is focused on the likelihood that the herd will be sustained until the next rainy season. “2021 rain season will tell us what we will or won’t do,” he said. “We would have to hold on with what we have til then and hope it rains.” If it doesn’t? “We’re probably gonna get rid of everything.”

Means believes solutions rely on the climate, not adaptation. “We can’t start irrigating country or nothing like that — it’s not farm country,” said Means. “We just have to get rain to stay going.”

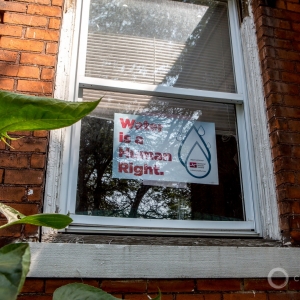

Water, Texas is a five-part series on the consequences of the mismatch between runaway development and tightening constraints on the supply and quality of fresh water in Texas.

The story of Texas is the state’s devout allegiance to the principle that mankind has dominion over nature. In 2020, the pandemic, climate disruption, and ever-present challenges with water supply and use are writing a much different story of vulnerability to nature’s bullying, and to government’s uncertain capacity to adjust.