For Honolulu, Rising Seas Deliver Flood Risks Three Ways

The biggest source of flooding linked to sea-level rise for Hawaii’s capital city comes not from the sea itself. It comes from underground.

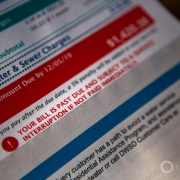

King tide flooding in August 2019 in Mapunapuna, an area of Honolulu north of Daniel K. Inouye International Airport that was built on fill and floods during the highest tides of the year. Photo courtesy of Hawaii Sea Grant King Tides Project, 2019

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Build a wall?

It seems like an intuitive response for protecting a coastal city from rising seas. Just raise your external defenses. But the intuitive response, in certain cases, is also the wrong response, says Shellie Habel.

If the plan to prevent flooding in a city like Honolulu were to be simply block the ocean, “it’s not going to work,” Habel told Circle of Blue. Water has other, less obvious ways of invading, and that stealth movement has implications for water pollution and transportation in Hawaii’s largest city.

Habel is a coastal geologist with the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources and Hawaii Sea Grant. She is the lead author on a study that investigated three flooding pathways in Honolulu, all of which are a consequence of rising seas. The study is the first to attribute the percent of flooded area in the city that is due to each factor individually and in combination. The likelihood that floods will come from multiple pathways simultaneously — and cause more infrastructure damage — rises along with the seas.

In Honolulu’s case, a sea wall would be a losing strategy against sea-level rise because a wall would not address the most serious flooding problem. The largest source of inundation for the city’s roughly 350,000 residents is not the ocean. It’s groundwater.

Habel and her colleagues found that little more than 2 to 3 percent of flooded area in Honolulu’s urban core is a result only of overland marine flooding. That range holds for the four sea-level elevations that the study looked at.

Groundwater flooding, by contrast, is the predominant individual source of flooding. How does this happen? Groundwater in the coastal region is hydrologically connected to the ocean. When the Pacific swells, so does the inland water table.

A hypothetical wall on the Honolulu waterfront would fail to prevent flooding, Habel said, because water would still bubble up from underground and come through backed up storm drains, which are the third flooding pathway. Groundwater flooding today swamps basements and roadways in low-lying areas and is noticeable in underground parking garages.

“So even if you put in a sea wall, even if you change the type of drainage management, you still have flooding,” she said, adding that a solution that only addresses marine flooding will not work because 97 percent of the total area that is projected to flood will still flood from rising groundwater and storm drain backups. Places like New Orleans and cities in the Netherlands, which also have groundwater flooding problems, employ pumps for that purpose. “In order to mitigate all the flooding you have to adapt to all three pathways.”

And if you don’t account for all three?

“If you don’t do that, it’s totally ineffective.”

Attacks on Multiple Fronts

The study, which was published in the journal Scientific Reports, began by looking at a set of flooding thresholds and estimating how often the seas would exceed those thresholds. Habel did the research while working on her Ph.D. at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

The lowest threshold reflects an event that already occurred: a king tide in 2017 that pushed water levels abnormally high. King tides are the highest tides of the year and are seen as a sea-level rise preview. The other three thresholds — called minor, moderate, and major — were based on a federal government data set.

Water bubbles up from a storm drain in Mapunapuna, an area of Honolulu that frequently floods during the highest tides of the year. Photo courtesy of Hawaii Sea Grant King Tides Project, 2017

As the seas rise, the land area that is flooded by water from all three pathways simultaneously — from ocean, groundwater, and storm drain backups at once — rises substantially. It goes from 18 percent of the flooded land at the king tide threshold to 55 percent when sea levels reach the major flood threshold.

What’s valuable in this study is the attribution of how much flooding comes from each pathway, said Kristina Hill, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies flooding and urban design. The amount that is linked to groundwater should be an eye-opener, she said.

“This indicates how important it is to understand groundwater flooding,” Hill told Circle of Blue.

Inspired by previous flooding studies in Honolulu and elsewhere, Hill is directing research in the San Francisco Bay Area that is investigating the connections between rising seas and rising groundwater. As in Honolulu, Hill has found that groundwater-related flooding in the Bay Area, a region that has shallow water tables, urban developments built on former wetlands, and rising waters, is an overlooked risk.

The areas in Honolulu that are among the most vulnerable to flooding are also those that are built on former wetlands that were filled in with dredged material.

“They only put enough fill in to keep it dry at the moment,” Habel said referring to when areas like Waikiki were dredged and commercially developed, nearly a century ago, in the 1920s. “When they were engineering those projects, I doubt they were thinking about sea-level rise.”

Cesspool Failure

Higher water is more than a nuisance. It causes real damage — damage that increases the higher the waters rise.

Besides flooding thresholds, the study also assessed current and future flooding threats to roadways, storm drains, and sewage ponds in Honolulu. Buildings and property are also at risk but were not a part of this research.

No sections of roadway were impassable at the level of the 2017 king tide, but traffic slowdowns would occur on nearly a half mile of streets. High tide flooding is already a problem in Mapunapuna, an industrial district north of Daniel K. Inouye International Airport. Flooding in the area today is completely driven by rising groundwater. Habel said that business owners there check the tidal charts to know when they will have trouble accessing their businesses.

More significantly, the study indicates potential increases in water pollution.

In Hawaii, cesspools are frequently used as a means of sewage disposal. Cesspools are pits or wells that hold kitchen and bathroom wastewater from a house or business.

To function properly, a cesspool needs several feet of unsaturated ground between its bottom and the water table, where microbes in the soil can chew through the waste. Rising seas and rising water tables eliminate this unsaturated space.

Being below ground, cesspools are among the lowest elevation infrastructure in Honolulu, and therefore the highest risk for sea-level rise disruption.

Habel found that nearly 90 percent of the 691 cesspools in the study area would be rendered non-functional when the Pacific reaches the level of the 2017 king tide. In that scenario, 11 of the cesspools would be fully flooded.

Hill noted that she has found similar pollution concerns in her work. In the Bay Area, the issue is not cesspools, but soil that is contaminated by leaking storage tanks and former industrial sites. Rising groundwater could shake loose these pollutants and spread them into open waters.

“Every time I see them write ‘cesspool,’ I think ‘leaking underground storage tank,’” Hill said, reflecting on the circumstances in her home area. Underground tanks that used to hold oil and petroleum products at gas stations are a priority for environmental regulators.

Cesspools are also a known hazard, polluting rivers and marine waters with fecal waste. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency required all large-capacity units in Hawaii to be shuttered by 2005. These mostly served businesses and apartments. Still, there are an estimated 88,000 cesspools in Hawaii that continue to be in service, mostly for residences. In 2017, the state legislature passed a bill that requires the owners to upgrade them to septic tanks or connect to a sewer system by 2050.

Habel’s study provides a window into what that decade will be like. Sea levels that exceed the 2017 king tide, which at the time was an extraordinary event, could happen every day as soon as the 2050s if carbon emissions remain high.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!