HotSpots H2O: Climate Change, Pandemic, Violence Are Volatile Mix in Chad

Dar Nahim is one of the 42 sites currently hosting internally displaced persons in the Lake Chad region. © European Union/ECHO/Isabel Coello

A warming climate was already making life difficult in Chad, a landlocked country squeezed against the encroaching sands of the Sahara. Now, the coronavirus pandemic and a years-long conflict between government forces and the terrorist group Boko Haram are stoking tensions and imperiling livelihoods.

Nomadic communities in Chad depend on the environment to survive. According to Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, they normally leave the drought behind and follow the rainfall, yet restrictions placed on movement during the pandemic have kept the communities locked down in dry areas. The cattle are dying, along with residents’ food security.

“When there is drought for cattle, there is food insecurity for the people,” Ibrahim, the coordinator of the Association for Indigenous Women and Peoples in Chad, said in a statement to the United Nations Security Council earlier this month.

“Whether we have a lot of rain that floods crops, or drought, which shrinks resources, it ends in conflict among communities fighting for access to land or water,” Ibrahim continued. To her, communities are not killing each other for power. They are killing each other for water.

Unable to follow the rain, men are leaving their families to find work in the cities. The women and girls left behind are vulnerable, at a greater risk of murder, sexual violence, and enslavement by Boko Haram. There is nowhere else to get food, no store or market. All the communities can depend on is the rain, Ibrahim said.

Violence and insecurity in the region escalated in 2015 when Boko Haram expanded its reach throughout the Lake Chad basin. Since then, some 13,900 refugees have fled from Nigeria to Chad to escape violence from the terrorist group. Many communities in Chad struggle with food security and lack of water, sanitation, and hygiene. The simmering conflict, along with newly implemented Covid-19 restrictions, has prevented access to markets and depleted rations for citizens and refugees.

Furthermore, drought as a result of climate change has shrunk Lake Chad by 90 percent since 1960. Though lake levels stabilized in the last two decades, the people of the region still endure a lack of drinking water, proper sanitation and hygiene. In the country as a whole, these deficiencies result in an estimated 19,000 annual deaths.

“This is not the future we want for people,” Ibrahim said.

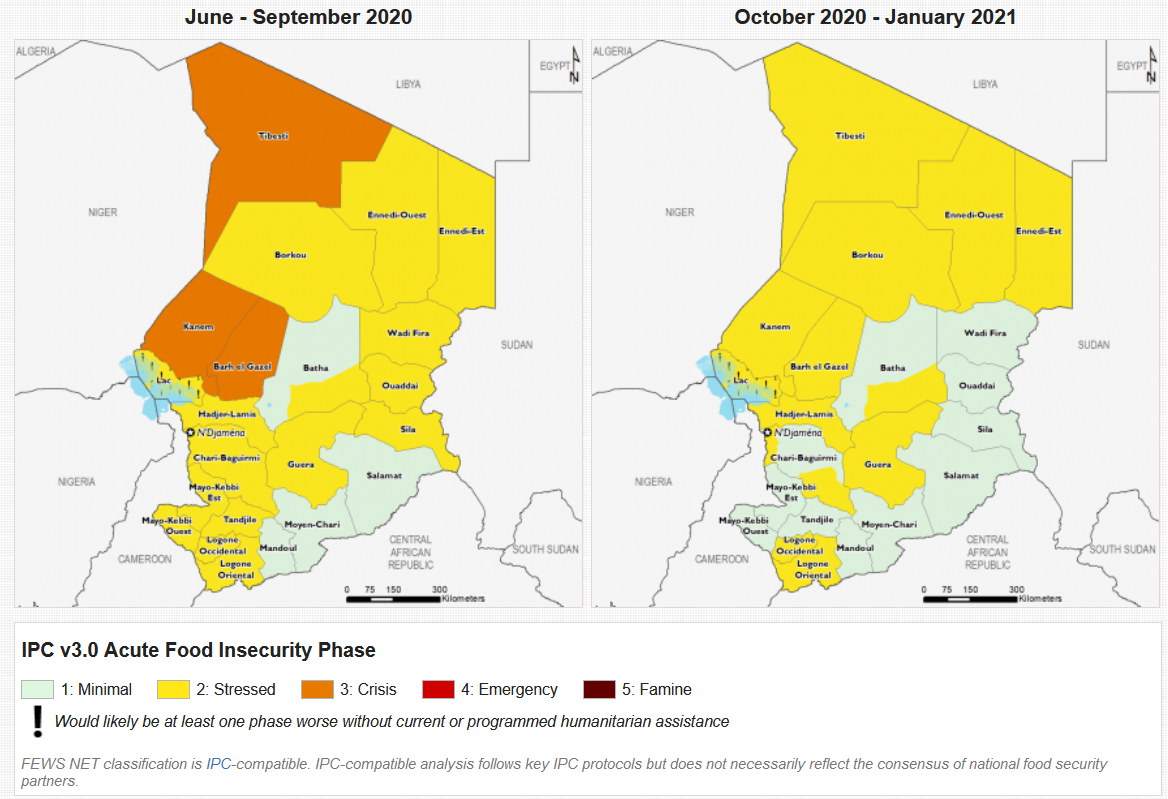

Food insecurity 2020 to 2021 © FEWS NET

Looking ahead, Ibrahim stressed the need for adaptation in the region. Humanitarian aid is limited due to violence, and does not provide a sustainable future, she said.

Ibrahim instead urged the Security Council to consider a “green new deal” for Chad and the other regions in the Sahel belt that would invest in climate-ready projects for herders and farmers. By emphasizing ecological solutions, Chad’s young population — nearly half of which is under age 15 — can direct its energy on adaptations that address the region’s biggest future threat: a warming climate and more erratic rains.

Elena Bruess writes on the intersection of environment, health, and human rights for Circle of Blue and covers international conflict and water for Circle of Blue’s HotSpots H2O.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!