Lack of Utility Data Obscures Customer Water Debt Problems

Inadequate data hampers understanding of who is most affected by overdue water bills.

October 12, 2020

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

More than one in five Baltimore residents meets the federal definition of poverty, and the city’s water rates have more than doubled in the last decade. Its aging sewer system is proving costly, undergoing $1.6 billion in federally mandated repairs. For large metro areas, the Queen City also has some of the oldest housing stock in the country, which is a risk factor for pipe leaks.

Together, it is a recipe for residents having high and unaffordable water bills and an indicator that many households might be in debt to the water department. But how many? It is hard to say.

A public records request submitted to the Baltimore Department of Public Works, the agency that handles water supply and billing, did not yield any results.

“DPW does not have custody or control of a record that captures the past due balances by the breakdowns you are seeking,” Jennifer Combs, a spokesperson, wrote to Circle of Blue. She went on to say that the department does not have the “proper personnel or resources to devote to creating and analyzing the data that would be necessary to respond to your questions.”

Combs’ response indicated another potential data source: the Department of Finance.

A subsequent public records request to the Department of Finance also ended in a roadblock. The department said it did not have data on customer water debt. Henry Raymond, the department director, suggested a U-turn.

“That data resides with DPW,” Raymond told Circle of Blue.

DPW ignored subsequent requests for data and declined to be interviewed for this story.

For legal advocates working in Baltimore, this exchange is not a surprise. In fact, obfuscation and delay seem to be standard practice for the Department of Public Works.

“In terms of how many people have extremely high water bills or leaks, that’s the type of info that all of us have tried to request from DPW and haven’t gotten very satisfactory responses from them,” Margaret Henn, the director of program management for Maryland Volunteer Legal Services, told Circle of Blue. Henn helps low-income Baltimore residents resolve water bill disputes.

Alexandra Campbell-Ferrari, executive director of the Center for Water Security and Cooperation, said that there are relatively few requirements in Maryland and nationally for utilities to publish information on customer debt levels or the number of customers disconnected from water service.

“There isn’t a lot of transparency with respect to the challenges certain families face in affording their water bills,” Campbell-Ferrari told Circle of Blue.

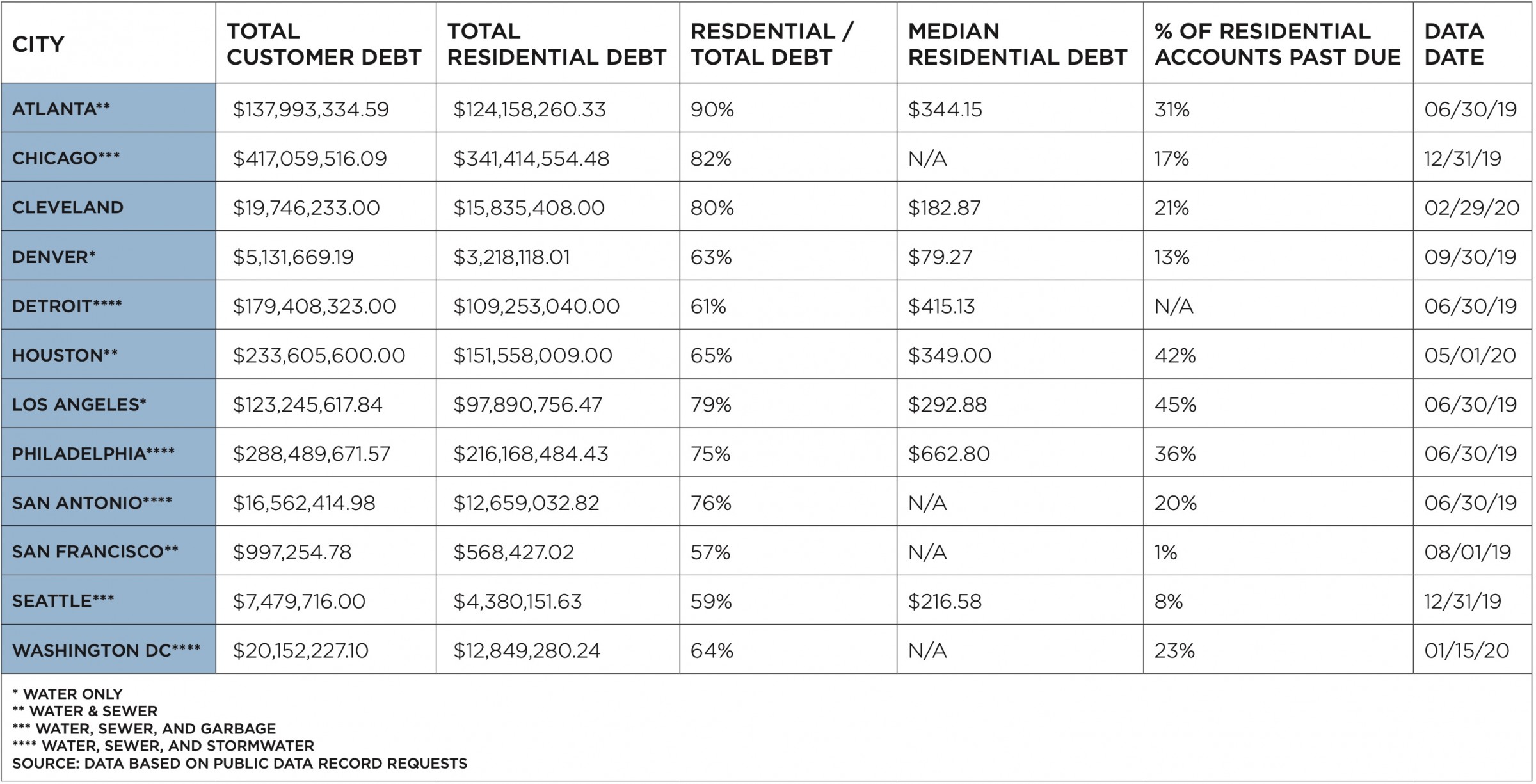

The scope of those challenges is becoming clearer. A Circle of Blue investigation of public water utility finances found that more than 1.5 million residential customers in a dozen large U.S. cities owed more than $1.1 billion in past-due bills. The data was collected largely before the Covid-19 put millions of people out of work. In the last six months cities have seen the number of past-due accounts soar. Customer debt is now undoubtedly higher. Louisville Water, to cite one example, typically has about 2,000 customers with overdue bills. Now, about 16,700 are behind.

Who is in debt? Are they mostly struggling families? Or are relatively well-off households forgetting to pay their bills? Are there pockets of water debt concentrated in certain areas of the city? Or is it scattered among neighborhoods?

Based on the responses from public records requests and interviews with water researchers, answering these sorts of questions is difficult with the data and analysis that utilities are currently bringing to the table.

“The problem exists across the country,” said Campbell-Ferrari, who encountered a similar lack of data when completing a report on water shutoff policies in Maryland.

‘A Complicated Undertaking’

For customer debt data, the Baltimore Department of Public Works was an outlier. It was the only utility that did not provide any data at all in response to public records requests for information on total customer debt, residential and nonresidential debt, median debt per account, how long the debts have been outstanding, and debt by ZIP code.

Though most utilities were able to generate some data, the quality and depth of their information gathering varied widely.

Detroit, for instance, could compile water and sewer debt by ZIP code. Chicago and Houston provided customer debt data with even greater detail. They subdivided their data not only by ZIP code but also by the age of the debt — how much was 90 days past due, 180 days past due, 365 days past due.

The age of the debt is important, utility officials say, because it indicates the likelihood that the utility will collect it. Older debts are less likely to be paid.

This level of detail was the exception. When asked for debt levels by ZIP code, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power said such an aggregation was beyond the utility’s existing technical capacity.

Denver Water could not provide ZIP code-level data, either. “This would be a complicated undertaking and we don’t readily track the information by location in a way that would render this information easily mappable,” Todd Hartman, a Denver Water spokesperson, wrote to Circle of Blue.

Brian DeNeve, a spokesperson for Milwaukee Water Works, said that it would be “difficult and time consuming” to extract basic information from the utility’s databases. For that reason, the utility did not provide statistics in response to a public records request: the number of residential accounts that were past due, the total residential past-due balance, and the median past-due balance. To gather these data points, the department would have to create “multiple programs and tracking methodologies” — tasks that are not required by Wisconsin’s Public Records Law and its interpretation by the state attorney general, DeNeve said.

These deficiencies were not a surprise to Manny Teodoro. A public policy scholar at the University of Wisconsin who focuses on water utilities, Teodoro said that most utility billing systems are rudimentary.

“Billing systems were designed to send bills and collect and record payments,” Teodoro told Circle of Blue. “They were not designed to do any other analysis.”

Teodoro has first-hand experience. A year and a half ago, he was working with a utility in a Midwestern city of about 100,000 people to evaluate its affordability program. After a year, he couldn’t get the billing system to provide any useful data.

“We gave up,” he said.

Data Transparency

The scarcity of customer debt data is striking given the adjustments cities have made in recent years to become more data savvy. The “smart city” promises advancements and efficiencies: identifying problems and targeting services to those needs.

The open data movement has come to cities large and small. Boston publishes 164 data sets on topics like crime, energy use in buildings, rainfall, and fires. Austin tracks where city workers have scrubbed graffiti. San Francisco catalogues the fences and gates maintained by the Recreation and Parks Department.

Water utilities were later to the game than most sectors, but even stereotypically stodgy water departments have started to embrace new tools. Advanced meters track household water use by the hour and minute. Sensors in sewer pipes monitor overflows and detect leaks. South Bend — the small Indiana city known for nearby Notre Dame University and Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination this year — installed a sensor network in its sewer system to help control overflows.

Some utilities are experimenting with newer technologies, applying AI and machine learning techniques to their distribution networks to identify the pipes that are most likely to break and therefore should be at the front of the line for replacement.

Those advancements are mostly about hardware, the physical structures that a utility operates.

The analytics revolution has been slower to arrive in customer services — the space where water overlaps with economics and demographics.

The deficit is evident in data about homes and businesses where water service has been disconnected. Shutoffs stem from high debt loads, but few utilities can say how many water service disconnections are due to residents not being able to afford their bills.

Lawmakers, if they are willing, can force utilities to be more transparent. The California Legislature passed a bill in 2018 that requires utilities to report the number of shutoffs they complete each year. Yet no such requirement, in California or elsewhere, exists for tracking customer debt.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton